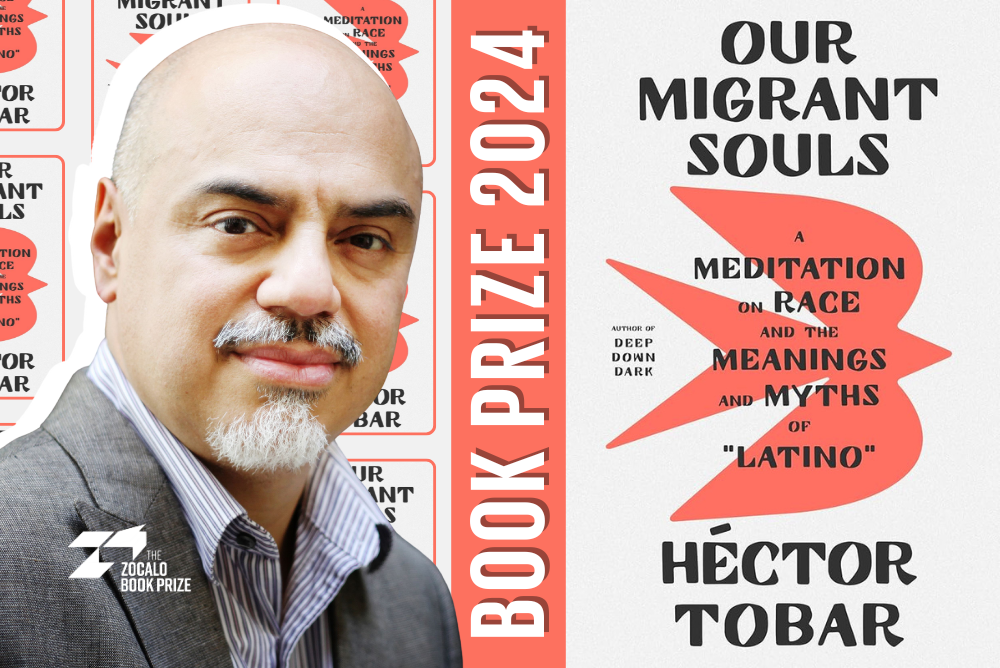

Photo courtesy of author.

Héctor Tobar is the winner of the 2024 Zócalo Public Square Book Prize for Our Migrant Souls: A Meditation on Race and the Meanings and Myths of “Latino.”

Zócalo has awarded the $10,000 prize yearly since 2011 to the nonfiction book that best enhances our understanding of community and the forces that strengthen or undermine human connectedness and social cohesion. The 13 previous Zócalo Public Square Book Prize recipients include Heather McGhee, Michael Ignatieff, Danielle Allen, Jonathan Haidt, and most recently, Michelle Wilde Anderson.

Tobar is the author of six books, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, and a professor at UC Irvine; he was born and raised in Los Angeles and is the son of Guatemalan immigrants. Our Migrant Souls blends personal, local, and global histories to explore what it means to be “Latino” today. (The quotation marks are Tobar’s, and they address the word’s capaciousness and its limits.)

Our Migrant Souls is “an essential read for anyone looking to deepen their understanding of race, identity, and the immigrant experience in America,” wrote one of our Book Prize judges. “Tobar’s exquisite use of the written word is a rare delight in and of itself,” noted another. Yet another concluded that the book “felt like a collage, or as the title says, a meditation. That felt just right as a way to show a sprawling, socially constructed identity.”

The annual Zócalo Book Prize event, featuring a lecture by Tobar, who will also be interviewed by USC historian and 2020 MacArthur Fellow Natalia Molina, will take place on June 13, 2024, at 7 p.m. PDT, both live in person in Los Angeles and streaming on YouTube. In addition, the program will honor the winner of this year’s Zócalo Poetry Prize. Zócalo’s 2024 Book and Poetry Prizes are generously sponsored by Tim Disney.

We asked Tobar about the connections between Latino identity and social cohesion, how Los Angeles shapes his work, and what books he recommends readers dive into after finishing Our Migrant Souls.

How does “Latino”—the word, the concept—contribute to strengthening social cohesion and community in America?

To me, Latino is an expression of a common ground that a people have in relation to U.S. history. All the ethnic and race labels of the United States have been created as counterpoints to white. They’re all inventions; they’re all social creations. The invention of “Latino” is a response to a very real kind of exploitation related to the creation of the American empire. The United States cuts its teeth as a world empire in Mexico and Central America. It creates wealth based on a system of inequality, an exploitation of resources, that leaves Central and Latin America and the Caribbean as peripheral states, as places of lower wages and extraction of natural resources, and this leads to a migration to the “great north.” In other ways, Latinos are an internally colonized people, by the U.S.–Mexico War drawing a line in the sand between these two countries, and the gradual militarization of that border, which we see today.

The people we call “Latino,” we all share this story, a story of empire, a story of having to travel across a border or having a border cross us. So Latino is this term of solidarity among those peoples. I think that it contributes to social cohesion because it’s a kind of desire and expression of keeping alive the memory of dispossession, of exploitation, of oppression, and resistance. Latino is saying, we’re all these different colors and places, but we have a common story that binds us together. It’s also the way we think of ourselves as citizens of this country, as people who have this common heritage and are going to bring that tradition into the U.S. as other peoples have before us.

On the flip side, how does this term and idea undermine human connection?

I put “Latino” in quotes because it’s a misnomer. In a certain sense, it’s kind of like embracing “white” as a definition. The people who can call themselves Latino, we are of many different backgrounds, and we—many of us, like me—have Indigeneity or Blackness in our background. To call yourself Latin or Latino is to embrace a word that has a European origin and a distinctly European culture. To me, it is something that erases the complexity of this story of human interaction. So you have to add terms to it to make it work, Afro Latino, for example, to explain what it’s like to be Puerto Rican or Dominican. And Latino as a national identity, as a kind of ideology put forward by various elites in Latin America, is very Eurocentric. In the Dominican Republic, especially, there is an idea of Dominicanness as superior to Haitianness. The countries share an island, Hispañola, and there is this strong current of official racism against Black people. In the Dominican Republic, the vast majority of people have an African ancestor. So Latino glosses over that. It glosses over the colorism in our own families, to favor lighter over darker skin, to have ideas about beauty, to embrace European features and coloring as more beautiful than African features and coloring. So that is why I felt the need to put Latino in quotes in my book, because it’s also a really fraught term.

How would this book have been different if you had written it a few years earlier?

I have a concrete example of how it would have been different if I had written it years earlier because I did write it years earlier. In 2005, I published the book Translation Nation, which is a travelogue through the Spanish-speaking United States in an attempt to show and explain how Latino people were changing the face of the U.S. and its conception of itself as a country. That book was very optimistic. It was written in the early years of the anti-immigration movement, when a lot of us believed there was an immigration reform around the corner that was going to allow the millions of people with undocumented status to receive a path to citizenship. We had leading Republican political figures supporting that path to citizenship, including George W. Bush. And so I felt very optimistic about where Latino immigrants were headed. To me, that book was a celebration of the ambition, the civic spirit that I saw in Latino immigrant communities not just in L.A. but all over the country.

Move forward 18 years, and there was no immigration reform. The walls got taller, the border became more militarized, the rhetoric turned nastier and swept up more chunks of the American political class. And so my book had to address the pain, the hurt, the anger caused by that great shift in American political discourse.

The book meditates on the heroic nature of border crossings and of immigration stories—but that’s not the prevailing narrative of the Latino journey. How do you think America’s larger culture can make the Latino story feel epic, as you see and describe it?

Privately and in the intimate spaces of their family, people understand their stories that way, but they’re not validated by the larger culture. The absence of narratives about us—full, complex, textured, epic narratives—really is something that keeps people of Latino descent from feeling their full power as members of the United States and as civic actors and all the things that we can be in this country.

It’s ironic that Los Angeles, the home of this incredible industry of moviemaking and TV-making and streaming-making, has a Latino plurality and yet there are so few interesting Latino stories in those different media. It’s not for lack of trying. That’s something that we have to work on as artists and that will also happen when we as cultural consumers force ourselves into those spaces—when we start getting in people’s faces. I think that will happen as part of a larger movement that isn’t just about culture. When the desire of Latino people to fight racist ideas about us and to fight for the full rights of everyone in our families, people who have labored here for generations—when that is at the center of American political discourse, I think the cultural things will follow.

How did Los Angeles shape this book?

Los Angeles is a great crossroads of the world. It’s a place where you can’t avoid the history of all the diasporas whose roots across the globe lead to this place—we have the Armenian diaspora, the Korean migration, the Jewish diaspora, the Great Migration from the South of African Americans, the Filipino diaspora! I could go on and on and on. L.A. as a world city forces you to think about your own experience in the context of the globe and its migrations and all of the different imperialisms whose crimes end up with a guy or a woman arriving with their suitcase at Union Station or at LAX. That’s for starters.

To have lived through the crises of the 1990s in Los Angeles, specifically many recessions and the uprising or riots of 1992—I’ve seen all that. It’s a lot to process as a writer and thinker, and it’s a gift because I think L.A. has taught me a lot about itself but also about the U.S. and the world. My own personal story, as I describe in Our Migrant Souls, involves this white supremacist neighbor, and an African American activist who became my godfather. Even as an infant and a 5-year-old, my life was already inserted into this larger American narrative. L.A. has given me all that and more.

What books would you recommend someone dive into after reading Our Migrant Souls?

Of course I would recommend James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, which is the inspiration for my book. And W. E. B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk, to which my book title is an homage. I would recommend Mae Ngai’s Impossible Subjects for those who really want to get grounded in immigration history and the race ideas behind immigration policies. Another book I read recently is Kelly Lytle Hernandez’s Bad Mexicans, which is this wonderful story not just of two Mexican revolutionaries but of underground Los Angeles in the early parts of the 20th century. It’s important for people to know that people working for revolution and change came here.

The book I always recommend to friends is Edith Grossman’s incredible translation of Don Quixote. We’re supposed to be Hispanic, Latino, and here is not just the greatest Spanish novel ever written, but maybe the greatest novel ever written, and maybe the first novel ever. But to me the interesting thing about Don Quixote is that it’s a work about the power of realism. Because Don Quixote’s mind is trapped inside this romance notion of what his life should be, and yet there are all these things happening around him that are so interesting. The context around it is of multicultural Spain. The whole conceit is it was written in Arabic, and Cervantes is translating it.

To me Don Quixote is not just a beautiful, amusing, and, in the end, deeply moving read but also something that reveals this constant of human history: the mixing of peoples and the creation of new cultural moments from old ones. That’s something that’s changed my vision of history. Once I understood how each United States race category hid these incredible varied histories of migration and mixing, I saw that everywhere in human history is this joining of peoples. It’s more common and more natural than people realize, and to me that’s part of the beauty of Don Quixote.

Send A Letter To the Editors