A young boy uses a digital tablet in bed. Courtesy of Adobe Stock Images/© jackfrog.

A great conflict is tearing this country apart, bitterly pitting generations against each other. It’s not immigration or “Medicare for all.” It’s the fight over how much time kids can spend staring at screens.

Call it the Great Screen Time War of 2019.

And I thought I was winning the war on behalf of my three sons—until California intervened in favor of the screens.

To be a parent in 21st century America is to be whiplashed by contradictory advice. Give your children space to explore, but don’t let them out of your sight for a second—or some bystander will call the police. Teach them to mind their manners, but also train them to be “disruptors” who will shake up the world for the better. Make sure your children follow current events and participate in civic life, but shelter them from the media-dominating bigotry and vulgarity of President Trump.

But of all the double-edged directives aimed at parents, the one that most rankles me involves the internet and screens. To wit, I must keep my children away from screens to protect their health and their future; the World Health Organization just issued a highly publicized report covering screen time’s dangers, and the state of California recommends no more than 60 minutes of screen time after school. Yet, I am supposed to keep them online and in front of screens, where—also at the behest of the state—more and more of their academic work must be performed.

My wife and I have tried to square that circle with the Three Stooges, our three young sons, now ages 10, 8, and 5. During the preschool years, we all but banned TV and video watching. And we successfully discouraged the internet.

But then our oldest son hit third grade, when schoolwork and homework shift online. That’s also when the amount of work ramps up. There is one big reason for both the shifts: Third grade is when the state starts its standardized testing in public schools.

Since 2015 that testing, the California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress, or CAASPP, has been conducted online. If your kids are in the third through eighth grades, or in the 11th grade, they are sitting in front of screens and taking CAASPP tests this month.

To prepare for these tests, schools and teachers—quite naturally—put more homework and classwork online.

And that is how this parent lost the screen time battle.

In the early grades, we resisted getting a computer for our oldest, letting him use one of ours when necessary. But by the third grade, with the homework online, he needed his own, and so we bought a cheap Chromebook. It’s all been downhill from there.

Before the Chromebook, we had a simple, enforceable message—stay away from screens. Now, we were contradicting ourselves—“get on the computer and do your homework!” followed by, “get off the computer—too much screen time.”

On many nights, to do their homework, our two older boys are online for more than those state-recommended 60 minutes. Sometimes it’s more than that, because they are sneaky, and they drift away from homework to online games, as I had feared. What I didn’t anticipate was that they would be introduced to those games via the school.

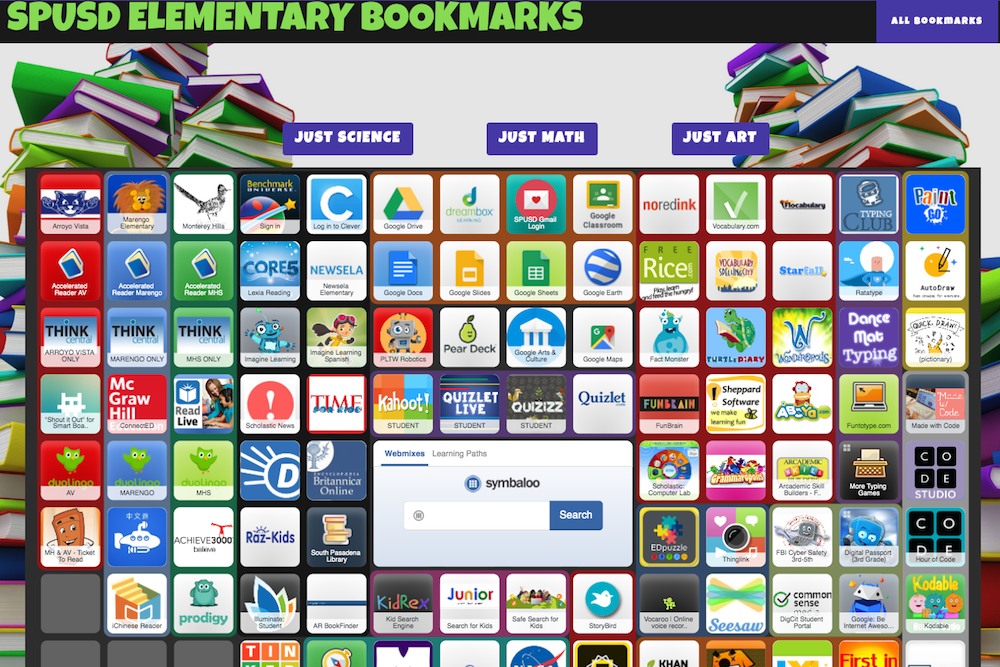

The website of our San Gabriel Valley school district links to more than 100 different sites, services, and apps to enrich their elementary education. To be fair, these enrichment extras have been vital to my two younger sons, who rely on online tools in their Mandarin immersion program to learn the tones and stroke order of Chinese characters. Even parents benefit personally from these online offerings. I used a foreign language enrichment program provided for my kids to learn some Italian before running a conference in Rome last year.

Home page of elementarylab.weebly.com, a website that links to hundreds of educational apps and sites. Courtesy of elementarylab.weebly.com.

But many of these educational offerings come from tech start-ups that have fused homework with video games. My second-grader now does spelling homework and learns typing via online games. In addition, my two older boys—and many of their friends—obsessively play a diabolical game called Prodigy, available via the district site, which mixes math problems with online fighting and the collection of different online rewards.

Unfortunately, we’re seeing warning signs of excessive screen use: The kids don’t want to go outside as much and play, bedtime has slipped later, and they don’t see friends as much as they used to. (They prefer to talk to those friends online). It is so hard to get them to stop that a majority of child-parent conflict in our household now involves Prodigy. The game was made by a Canadian company, so I’ve resorted to hoping it gets targeted for punitive tariffs.

When I complain about this to teachers, parents, and even state officials, most throw the problem back in my face. I’m told it’s my job as a parent to police screen time—just like our parents policed our TV time. But there’s a crucial difference: I wasn’t required to do my homework on TV.

I try my best. But most suggested screen time strategies involve just putting more pressure on parents to lock up computers and tablets, and to monitor their kids’ screens at all times. I’m sorry, but it’s hard enough to just enforce time limits. And I worry about my own screen time. After long work days in front of a screen, is it good for me to spend evenings and weekends staring at their screens?

This now ubiquitous problem is thick with ironies. I make sure the boys play sports, but screens are invading that world too. I’m a Little League coach, and this season I was required to keep score on an app called GameChanger. So even when I’m on the baseball diamond, I’m looking at a screen.

One expert recommended that I develop a “family media plan,” but the American Academy of Pediatrics’ tool to do that is, naturally, online.

Of course, there is no going back. Too much has been invested in educational technology, and this environmentally minded state, which is now considering a ban on paper receipts, could ban paper homework before too long.

But if screen time proves to have all the long-term effects on kids’ brains that some media researchers fear, then the difficult job of policing should not be left just to parents. Strong action from the state will be required, including changes in how the schools distribute homework, provide online enrichment, and conduct testing.

Send A Letter To the Editors