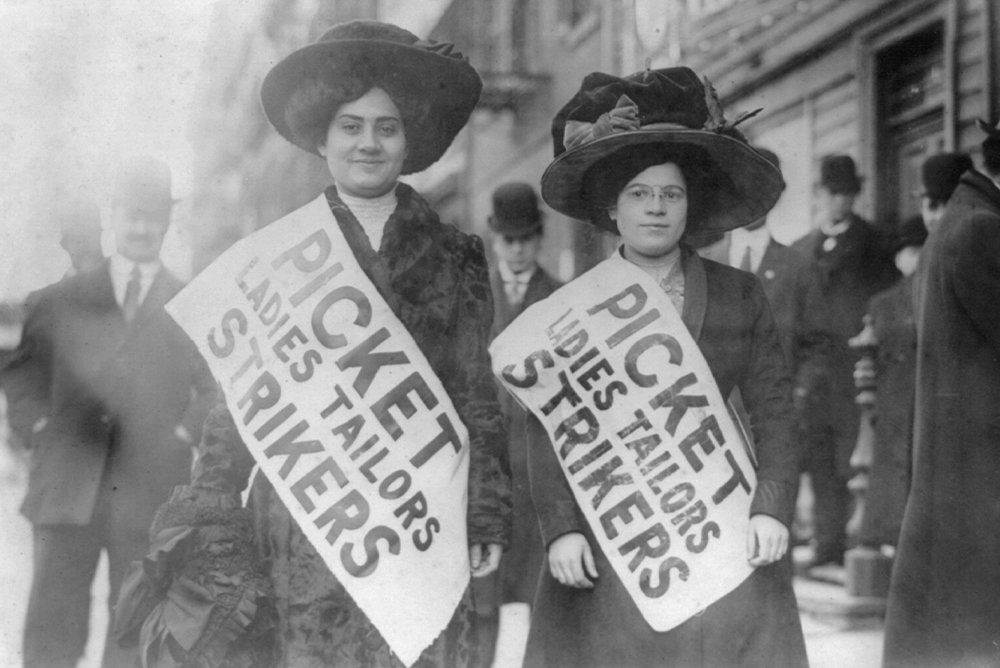

The birth of the ready-made garment industry exposed the ills of mass manufacturing, historian Einav Rabinovitch-Fox explains. Pictured above are two garment workers picketing in New York City during a 1910 strike for better working conditions. Courtesy of author.

Attention-grabbing headlines constantly alert us to the ills of fast fashion. The multi-billion dollar industry churns out mountains of inexpensive-but-stylish clothing, much of it sewn in sweatshop-like factories in Asia and Latin America and sold by popular brands such as Shein, H&M, and Zara. The industry exploits workers, uses harmful chemicals, and causes environmental damage to the planet. The garments it produces are of poor quality, which means consumers keep coming back for more—and the cycle of harm repeats.

Social and environmental justice advocates taking aim at fast fashion direct their criticism (justifiably) toward big retailers and powerful corporations. But some also point fingers at ordinary consumers, who—with the aid of social media and online trade—play into the wasteful ethos that perpetuates this industry. Meanwhile, defenders of fast fashion claim that its global nature is democratizing, and makes style accessible to the masses.

People understand this debate as the product of the current consumer economy and the impending environmental crisis, but it is not new. The problems of fast fashion, as well as calls for ethical consumption, have characterized the garment industry from its beginning.

The rise of the ready-made industry in the late 19th century, which offered the masses affordable clothes in standardized ready-to-wear sizes, is often celebrated as a great moment in the democratization of fashion.

No clothing item represented this revolution more than the shirtwaist. Modeled after a masculine dress shirt, the shirtwaist was often worn together with a skirt, creating a new style known as the “ensemble.” It replaced custom-made dresses fitted to specific bodies, typically sewn by seamstresses or by the wearers themselves. Marketed as appropriate for business, leisure, and everyday wear, the shirtwaist ensemble quickly established itself as a staple in women’s wardrobes.

The design’s simplicity and the fact that it did not require close fitting made it extremely adaptable to mass production and standardization. While shirtwaists could be sewed at home by following a pattern, most women bought theirs factory-made, whether from department stores or pushcart vendors in the street. Growing rapidly in popularity, the shirtwaist was responsible for the expansion of the women’s ready-made clothing industry, which grew in product value from $13 million to $159 million dollars between 1869 and 1899.

Shirtwaists came in a variety of styles and prices, ranging from mannish-tailored waists with basic lines to elaborately embroidered designs with lacy inserts and frilly ornaments. Each woman could choose her own style according to the event or time of day, but more often it was according to her financial means. Yet even working-class, immigrant women—many of whom worked in the garment industry themselves—could create a seemingly diverse, fashionable wardrobe without spending a week’s pay by pairing a few shirtwaists, each costing less than a dollar, with one skirt. The shirtwaist was instrumental in working women’s assimilation into American society and culture—enabling them to appear as fashionable as their middle-class and native-born peers.

Ironically, these same women could not afford the department store-quality shirtwaists they helped manufacture. As Clara Lemlich, a garment worker and a union activist attested, “The garments we work on are very beautiful, very costly—very delicate. Some of them sell for a hundred and fifty dollars. Such as you could never dream of buying for yourself.” Lemlich and her peers had to compromise on poorly made shirts that often did not last more than a few washes before falling apart.

It was not just the poor quality of inexpensive shirtwaists that exposed the ills of mass manufacturing. Working conditions in many of the garment factories were exploitative. Shifts were often 12 to 14 hours a day, six days a week, for only a few dollars wage. Workers were cramped into stuffy, dirty rooms with poor ventilation and lighting. And while many of them organized and went on strikes to improve these conditions, employers and the public often ignored their pleas—putting profits and fashion over people.

Days after the Triangle Factory Fire, protesters mourned the victims and demanded better working conditions. Courtesy of author.

That began to change in 1898, when a group of middle-class women sought to use their buying power to bring an end to the harms of fast fashion. Led by social reformer Florence Kelley, the National Consumer League (NCL) launched a campaign to target women consumers, encouraging ethical consumption by creating a “white label” for clothes produced under fair and safe conditions.

Modeled after the idea of the “union label,” the NCL’s white label indicated “clean and healthful conditions” of both the clothes themselves, which were free of hazardous materials, and for the workers who made them. NCL pamphlets such as “The High Cost of Cheap Goods” encouraged shoppers not only to look at bargain prices and popular styles when buying clothes but also to understand what lay behind seemingly great deals.

NCL members appealed to consumers’ sense of justice and called them to be responsible for their choices. “Don’t say… that by buying ready-made clothes at a bargain counter you are aiding in the support of many of your sex,” warned one member. “You are not; you are simply making it possible for the sweatshop to remain open.”

The white label campaign had some successes, but it was only in 1911 that the public became aware of its acute necessity. On March 25, flames engulfed the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory building, and New Yorkers watched in horror as hundreds of workers burned or jumped to their deaths. The 146 victims, the majority of them young women, offered a stark testament to the deadly cost of the pursuit of fashion.

Shocked by the tragedy, the public demanded action through mass memorials, rallies, and other forms of outcry. In the aftermath of the fire, the New York State legislature created the Factory Investigating Commission, which enacted more than 30 bills addressing sanitary conditions and workplace safety, imposing fire codes and other standards. The International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, which only months prior to the fire organized one of the most impressive strikes in New York City history, more than doubled its membership, and turned into one of the most influential and militant unions in the country.

The fashion industry still suffers from many of the same problems that plagued it over 100 years ago, at the time of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. Yet if it was middle-class consumers’ proximity to the fire that allowed it to spur outrage, today we are detached, both physically and psychologically, from the process by which people make our clothes. If it’s easier today to ignore the harms of fast fashion it is not because the harms are unfamiliar or new. It is because they are happening far away.

“Consumers… can, if they will, enforce a claim to have all that they buy free from the taint of cruelty,” Florence Kelley professed in 1914, believing that organized action and human solidarity could eventually bring change.

The NCL ended its white label campaign a few years later, in 1918, but Kelley’s message is still relevant today. Making the effort and looking beyond the price tag and the instant rush of shopping is our responsibility: to the workers who make our clothes, to the planet, but most of all to ourselves.

Send A Letter To the Editors