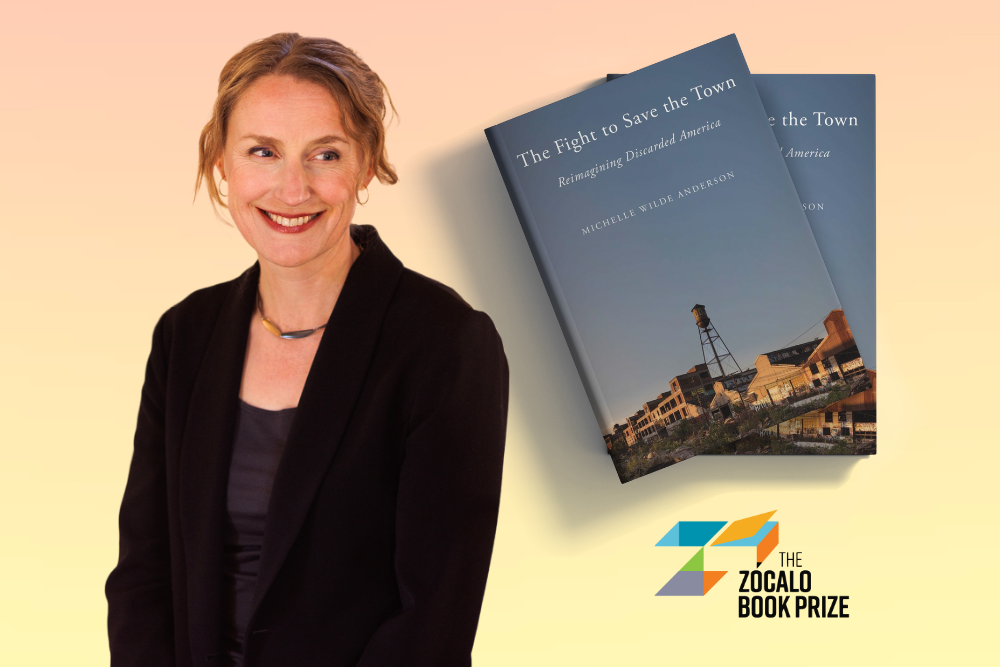

Photo of Michelle Wilde Anderson by Scott MacDonald. Illustration by Nick Yang.

Michelle Wilde Anderson is the winner of the 2023 Zócalo Public Square Book Prize for The Fight to Save the Town: Reimagining Discarded America.

Zócalo awards the $10,000 prize annually to the nonfiction book that most enhances our understanding of community and the forces that strengthen or undermine human connectedness and social cohesion. Our 12 previous winners—a mix of distinguished historians, social scientists, journalists, and public thinkers—include Michael Ignatieff, Sherry Turkle, Jia Lynn Yang, and, most recently, Heather McGhee. Anderson is a professor of property, local government, and environmental justice at Stanford Law School.

The Fight to Save the Town chronicles the stories of Stockton, California; Josephine County, Oregon; Lawrence, Massachusetts; and Detroit, Michigan—four places with histories of booms and busts, places that the rest of the nation often readily dismisses for their high levels of poverty and violence. But Anderson, who came across these communities as part of a larger research project on cities that had gone through municipal bankruptcy or state receivership during the Great Recession, found them to be places of hope. Here, people were coming together—to train trauma recovery counselors, to rebuild a broken-down library, to make parkland out of industrial wasteland, to stop foreclosures.

One of our Book Prize judges wrote that in telling these stories, Anderson is able “to explain how much place matters to humans, and what they’re willing to do to save a place buffeted by global forces rather than abandon it. … Anderson’s portraits are a stirring antidote to anti-government cynicism and a call to action against wealth inequality and the disinvestment from public goods.”

The annual Zócalo Book Prize event, featuring a lecture by Anderson, who will also be interviewed by Community Coalition CEO and President Alberto Retana, will take place on June 15, 2023, at 7 p.m. PDT, both live in person in Los Angeles and streaming on YouTube. In addition, the program will honor the winner of this year’s Zócalo Poetry Prize. Zócalo’s 2023 Book and Poetry Prizes are generously sponsored by Tim Disney.

We asked Anderson to talk about communities as teachers, the push and pull between federal policy and local problem-solving, and what it takes to build trust in a place of scarcity.

You explain in the introduction that you’ve chosen these four places because you “found them to be good teachers” about how chronic poverty emerges. How did you come to this particular mix?

These places helped me see the problems in very human terms, but also to see people moving against those problems. They had such incredible force as examples of hardships but also of creativity around solutions. I also wanted a range of places in the book that don’t let you write off the problem of concentrated city-scale poverty as a rural problem or an urban problem or a Democratic problem or a Republican problem or a Black city problem or a white area problem. I wanted to show that this citywide poverty phenomenon reaches across all of those categories.

These four places are symbolic to me of the kind of social movement work and progress that is possible. I think you can tell The Fight to Save the Town’s stories in dozens of cities and dozens of counties in the country. In that sense, this book is sitting with four places that are both special and ordinary. There’s a special category of people in any community who show up for the most vulnerable members of their town. When you’re open to finding those people and sitting with them, they lead you to others, and soon you have a sense of the kind of social network and safety net that is taking care of a place in its hardest times.

You write that part of the problem facing these places is the national narrative—which often tags them in harsh, nasty terms. How would you like to see the words we use to describe these communities, and others like them, evolve?

The way we talk about communities like this is its own problem. There’s a depth to the kind of stigma and dismissal we use, as though there are bullets flying and politicians being marched off in handcuffs and all kinds of hopelessness everywhere. When we talk about very poor communities in that language, it gives outsiders an excuse for inaction.

We can write these really pretty and somewhat voyeuristic eulogies of poverty that allow us to walk away because the problems are too hard and the situation is too dire. And I reject that hopelessness, and every person in the book rejects that hopelessness. They don’t have time for it. I think the way we talk about low-income places is exceptionally important for political will to support them at the state level and the federal level. Because people want to gather around progress.

That’s the narrative I sought to write, though never to sugar-coat how hard things are because they really are hard. Sugar-coating is its own kind of erasure and denial. But on the other hand, the truth includes all of this tenacious love and dedication and laughter. So many of the advocates I wrote about turn what might seem like tedious or even messy community events—like cleaning out a filthy river—into a moment of solidarity and community.

The book focuses on local solutions that come from community members themselves. But a lot of the disinvestment you chronicle is the result of federal legislation and statewide voting. What do you make of that tension, and where does that fit into this story?

The headwinds are ferocious, and the kinds of challenges that are totally beyond these communities’ control are really terrible. And that’s real. It is also real that any progress in a community has to be locally born. I think we just have to get more comfortable with allowing both of those things to be true at the same time. Local people have to be in charge of their own environment to the greatest extent possible without that serving as some kind of license for further withdrawal or further disinvestment or further action by outsiders. And on the other hand, outsiders or those enacting top-down strategies cannot imagine that they can fix all the problems in an area without that local network being engaged.

What struck me in the book is how much of the work in these communities is about building trust. How do people build trust among their neighbors, and in their institutions?

Trust is one of the giant themes of the book, and I did not know that when I went into these communities. I just didn’t appreciate the levels of mistrust that travel with scarcity. I mean mistrust at the institutional level, with nonprofits scrapping with each other to compete for grants, and at the interpersonal level, the way that violence undermines people’s trust in strangers as they walk down the sidewalk. I didn’t appreciate the degree to which mismanagement in the past, whether by a nonprofit or a government official, sticks around in people’s low expectations of those institutions in the future. Once people don’t trust each other, they’re not trusting each other to share resources. They’re not doing the restorative or reparative work with the general public that allows government officials or private nonprofits to earn back people’s faith and participation.

In all four of these cities, I came to be so moved by this incredible work to rebuild relationships and trust, just to get institutions sitting around a common table, leaders texting with quick asks. And that helped create, in an environment of a lot of scarcity, more complex interdependence. The community college does this, and the vocational school does that, and the mayor’s office is doing this piece, and a local business is doing that. Or really sewing blocks back together by systematically helping neighbors to need each other and become comfortable with each other, and just increase the number of people on sidewalks and in grocery stores that people recognize and feel trusting of.

At its worst, poverty can do so much to break people and institutions apart from each other. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

The book takes place in the shadow of the Great Recession and its aftermath. Do you see the country repeating the same mistakes right now, in a time of economic stress, and have you seen any improvements in how we shore up communities for moments of financial crisis?

Yes. The time period the book mainly sits in, 2016 to 2020, is a really interesting and relevant time period for thinking about us today because the work of that period relied on seeds that were planted during the most dismal days after the recession. Even when governments, including these four, were at their low points, people were still working on the cities’ problems, and they were still forging the human networks they were going to need when there were better resources around. And that was part of the reason I chose these places—because they didn’t hide under the table during their darkest times. Because at the same time the local governments were facing their hardest fiscal circumstances, their communities were facing the hardest intensification of poverty, whether it was foreclosures, the rise of homicides, or the early peaking of the opioid crisis.

The people I write about in the book showed up because people needed them to, and they built coalitions for change. By 2016, all of these cities had gone through really significant local political changes, where new leadership had come to the fore in the city government, in nonprofits, and was sort of ready to change the city’s major institutions. If I had to distill a time-based lesson from all of that, it’s that whether there’s money around or not, these problems aren’t going away on their own, and people have to keep leaning into them.

And then when the pandemic happened, this groundwork that was trying to pull society back together ended up being redeployed for a new set of emergency needs, and that too is just a deep reminder that we have to do this work of sewing society back together all the time, without a crystal ball about exactly what ways will be important to us in the future.

America’s more prosperous places are also facing challenges, including San Francisco and Los Angeles, where you live and where Zócalo lives, respectively. What lessons can these cities learn from the communities you profiled?

It’s interesting that all four of these places had heydays at various times. They weren’t wealthy at any point; for instance, Lawrence has always been a working-class city, without the industrial owner class living in it. But it was a really healthy, safe, modest town at many periods in its mid-20th-century history.

Looking at the long period of deindustrialization or economic change that they have gone through, it reminds me, as a San Francisco resident living in the heart of Silicon Valley, that prosperity is not inevitable and growth is not inevitable. The American project of bigger and better, growing always, has always been an illusion, but it’s especially an illusion in any given local place. It reminds me that you have to invest in the future when you’re doing well. You have to lay the groundwork for decline—for the expectation that the boom times don’t last forever. To me, that means investment in the physical infrastructure the city will need and live off of when it can’t be building a lot of capital projects and investing in big-ticket transit or climate adaptation or clean water. At least as important as that is you have to invest in kids and youth and your future workforce, and remember your people are your community, and they are the future of your town.

There are lessons for economic development, too—local governments, including in L.A. and San Francisco, tend to climb all over themselves to attract big-ticket employers who will bring jobs to their community. And sometimes they cut those deals in ways that could never survive a cost-benefit analysis. Really broke governments can’t play those games. They don’t have a prayer of attracting Amazon’s HQ2. What I came to admire so much about these communities is that they were seeking ways to invest in their people, not in Amazon. They don’t have enough money to hand it to a major multinational corporation, and instead redirect more modest dollars to real workforce investments to try to prepare their workers to get better jobs in their own town or somewhere else.

We all need to bring a greater commitment to our city populations and the broader time horizon of their needs, and not just seek out the next ribbon-cutting on a small batch of jobs here or there.

Send A Letter To the Editors