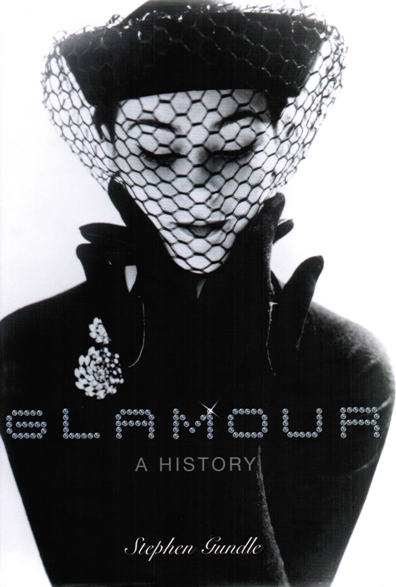

Glamour: A History

by Stephen Gundle

However elusive the quality of glamour may seem — restricted to the rich and the beautiful — Stephen Gundle argues that it can’t exist without some very ordinary things: shopping malls and magazines, cars and planes and hotels, movies and photographs. For glamour to maintain its power, he argues, it must be accessible, built from “materialism, beauty, and theatricality” and containing the promise that “anyone could be transformed into a better, more attractive, and wealthier version of themselves.” Glamour: A History breezes through the lives of the fascinating men and women who embody glamour – from Josephine, the wife of Napoleon, to Paris Hilton – along with the social, political and technological changes of the last three centuries that make glamour possible.

Monarchs of the past – Cleopatra, Marie Antoinette – are often anachronistically described as glamorous, Gundle notes. The word would not come into popular usage until the 19th century, thanks to a Walter Scott poem that defines it as a “magical power capable of making ordinary people…seem like magnificent versions of themselves.” And as this original usage suggests, glamour couldn’t exist without the dream of self-transformation and self-making – an aristocracy that banned entry except by birth couldn’t captivate the broader public.

What made glamour accessible is “commodity culture” and the ability to buy, or at least observe, the trappings of glamorous lives. In the 19th century, Gundle catalogs how cities became places to see and be seen, newspapers proliferated and printed the gossip of the higher classes, fashionable clothes became relatively less expensive, shopping became a pastime, and advertising an art. Merchants gave objects an “aura,” and shopping arcades were, as Walter Benjamin wrote, part of a “consumerist dream world.” In the 20th century, automobiles, planes, and hotels expanded social mobility and access to glamorous lifestyles; photography and movies brought highly constructed images of stars to big screens and fan magazines.

In Gundle’s view, it seems clear that men have been the primary inventors of glamour – they were the industrialists and journalists, the photographers and filmmakers, the producers of burlesque and the patrons of courtesans – but it is primarily women who embody glamour. Feminine sex appeal has been scrutinized and sold since the 19th century, he says, with the rise of the courtesan at a time when respectable women couldn’t partake in city life, and when men had the ready money and easy morals to patronize courtesans. Courtesans gave way to female entertainers, who perfected the art of the tease and of image-making through couturiers, portrait artists and photographers. Heiresses and debutantes, though born privileged like long-ago aristocrats, were still glamorous for the novelty of their lives, their conscious image-making, and their ability to spur fashion and beauty trends among the general public.

Still, the most compellingly glamorous women by Gundle’s telling are those who are made, not born, glamorous. He calls the Hollywood film star of the movies’ golden era the “most complete embodiment of glamour” – so many stars now famed for their enviable elegance, their paradoxical warmth and aloofness, were made from scratch: renamed, exercised and surgically enhanced into stars with carefully constructed personalities.

And for those who doubt that glamour can still exist today, when all the image-making is terribly transparent, Gundle keeps the faith: “The modern media work to render everything immediately visible and blend the private with the public. This undercuts the distance usually held to be necessary to cultivate mystery and arouse envy. Yet…glamour has not disappeared. The very plurality of enticing images…fosters an idea of glamour as an accessible idea, a touch of sparkle that can add something to every life.”

Excerpt: “In the period in which the major studios established their dominance over the leisure of the entire industrial world, no one was more highly polished, packaged, and presented than the men and women who became the majors’ main lure in their efforts to captivate the public. Suspended between the ordinary and the extraordinary, the real and the ideal, the stars were the gods and goddesses of a modern Olympus. To the man or woman in the street, it did not seem as if they worked at all for a living. Their fabulous lives were choreographed, pictured, described, and evoked by publicity departments that drip-fed the world’s press with news and information. For audiences worldwide, these alluring personalities were the stuff of fantasy. A fantasy, however, that was somehow accessible.”

Further Reading: The Star Machine and The Star as Icon: Celebrity in the Age of Mass Consumption

Send A Letter To the Editors