I have the same Hawai’i long form birth certificate as President Obama. Mine is four years newer. But it lists my parents’ race as “Korean” just as Obama’s birth certificate indicates his father’s race as “African”–a quirk birthers have cited as proof of fraud, since “African” is not a race.

My birth certificate isn’t the only thing I have in common with the president. In peculiar and intimate ways, I followed in Obama’s footsteps. I came from similar family circumstances, grew up in the same place, received the same education, and even shared the same teachers. So I have a peculiar and intimate perspective on the anti-Obama conspiracy theories of right-wing propagandists. The latest, a film by Dinesh D’Souza called 2016: Obama’s America, posits that the president’s foreign past, his upbringing in Hawaii, and his leftist education gave him an anti-colonial worldview that makes him a secret enemy of America.

I suppose that makes me, as an Asian American who enjoys piquing the status quo, a secret enemy of America too. All right Dinesh, let’s go there.

Like Obama’s parents, my parents came to Hawai’i to study at the university. My father was an erudite third-world immigrant who shared some of the same self-aggrandizing and self-destructive personality traits as Obama’s father. He also left our family when I was young to pursue failed dreams abroad.

Obama and I were raised in Honolulu only a few miles apart. In the fevered imaginings of D’Souza, the Hawaii of the 1960s and 1970s was a place teeming with Mau Mau-esque rage against the colonialism of the United States. Not true. I was there.

Obama’s tribe was far more Country Club than Counterculture. Obama graduated from the elite Punahou School in 1979. According to anti-Obama conservatives, it was a multi-culti academy teaching “oppression studies.” No way. Punahou, founded by East Coast Congregationalist missionaries in 1841 (when California was still part of Mexico), was easily the whitest, most Republican school on the island and the second-wealthiest private school in the western U.S. (The wealthiest private school in the U.S. was then, and is today, Kamehameha, a school for native Hawai’ians. It has $9 billion in assets). I recall, when I was a pre-teen attending a summer sports program at Punahou, feeling, for the first time ever, like a minority in Hawai’i. Some of Punahou’s white students were strikingly hostile to our local Asian-Polynesian culture, the only one I really knew.

Descendants of missionaries were present among Punahou’s students and staff and board of trustees. One of the most prominent trustees was Thurston Twigg-Smith, publisher of Honolulu’s more conservative daily newspaper and a descendant of a key figure in the overthrow of the monarchy. Two friends of mine told me (perhaps exaggerating) that “Twiggy” personally threatened them with expulsion for anti-establishment behavior. Far from the liberal culture warriors portrayed in fabulist biographies of the president, Punahou’s leaders were more like Dean Wormer from Animal House.

In 1979, as an eighth grader, I sat in Honolulu’s Blaisdell Arena as Obama and his Punahou School basketball team trounced my future high school in the state basketball championship. The final was 60-28. Our public school team had more black players than Punahou’s did. Obama, the sole African American, was a second-stringer, but played most of the game thanks to the lopsided score. Punahou’s star player was a 6’6″ pale blond haole named Dan Hale, who if not an actual descendant of missionaries could easily have played one in a movie. So much for stereotypes. (The same year, I also saw Earth, Wind & Fire in the same arena. While I am unable to confirm Obama was also there, I bet he was, as his devotion to the band at the time is well-documented.)

I last visited Punahou’s campus in 1982, when I was a high school senior. I had applied to Williams College, and my admissions interview was at Punahou, where three of the top administrators were Williams alumni. Walking past the lower school playground, I was surprised that the young children were not speaking pidgin but standard continental U.S. English. The kindly principal who interviewed (and encouraged) me was a New England transplant named Winston Healy. Punahou was an island within our island, exotic to me for its persistent channeling of 19th-century New England in 20th-century Hawai’i.

Native Hawai’ian activism and anti-colonial politics existed in the 1970s, to be sure, but Punahou then was about the worst place to look for it. The Hawai’ian cultural renaissance, which took off in earnest after Obama left, has revived the native language and other traditions. It’s a broadly embraced movement, feared by no one, and the tourist industry has even capitalized on it. Disney’s recently opened resort on O’ahu commissions local artists, hires community residents, and touts its Hawai’ian-ness to charge visitors $1,000 a night to stay there.

This is the capitalist, democratic Hawai’i Obama visits at least once a year. He’s not, despite what the film 2016 might imply, coming back to attend separatist cell meetings or enrolling his kids in Hawai’ian vacation madrasahs.

Speaking of madrasahs, how about Occidental College, where Obama studied in the early 1980s? I, too, attended Occidental, a liberal arts college in the Eagle Rock neighborhood of Los Angeles, and pursued some of the same activities as Obama, such as the anti-apartheid movement and writing poetry. My academic advisor and mentor was Roger Boesche, the political theorist and Alexis de Tocqueville scholar cited by Obama as his favorite college professor.

In his film, D’Souza suggests that people like Boesche helped Obama to develop anti-colonial views that were not those of “Washington, Jefferson, and Franklin.” Well, I took many courses from Boesche, beginning with the introductory political philosophy course Barry Obama had taken four years earlier, and D’Souza is correct that “Washington, Jefferson, and Franklin” were somewhat sidelined. Boesche devoted far more time to Jefferson, Adams, Hamilton, Madison, and Jay. (I bombed an exam question asking for a comparison of the philosophies of Jefferson and Adams because I said there wasn’t much to Adams). Boesche’s class wasn’t one in which we argued the legitimacy of the American Revolution; more often debates were over the merits of Federalist Paper #10 versus some others. That’s the sort of stuff you’d expect a future president to study, isn’t it?

Characterizations of Occidental as a radical hotbed, especially during the early 1980s, are equally disconnected from reality. The school had a required Great Books program in which Obama would have been enrolled. There were two alternatives in the program, one called European Culture, and another interdisciplinary program inspired in part by the ideas of University of Chicago professor Robert Maynard Hutchins.

In student life, Oxy had a decent football team, cheerleaders in short skirts, fraternities, sororities, and an active college Republicans group. The campus organization with highest participation may well have been the Christian student club. Alumnus Jack Kemp was a rising conservative star in Congress when Obama was in college, and I attended a campus ceremony in which Kemp was awarded an honorary degree. Kemp always praised Occidental, and, last year, the college named its football stadium in his honor.

This world from which Obama came is not frightening but familiar, a conventional place for anyone who might bother to look. But we were also familiar with some darker American traditions.

One of those traditions is the fear of conspiracy. When Hawai’i statehood was being debated in Congress, opponents argued against a minority-white state and raised the specter of communist infiltrators. Another is the fear of a non-white population. Obama’s father, like mine, came to Hawai’i in the years prior to the civil rights movement, when immigration was subject to quotas that allowed in only a tiny number of Asians and Africans. Civil rights activism led to the immigration reforms that eliminated country quotas, enabling large-scale immigration from Asia. It paved the way for D’Souza himself to come to America in 1978.

That civil rights movement, the one that D’Souza conflates with “anti-colonialism,” created D’Souza and Barack Obama. It also spawned, oddly enough, the conservative cartoon of Barack Obama-and of Americans like me.

Peter Hong is a Los Angeles-based writer. He spent 20 years as a staff reporter for the Los Angeles Times, the Washington Post, and Businessweek .

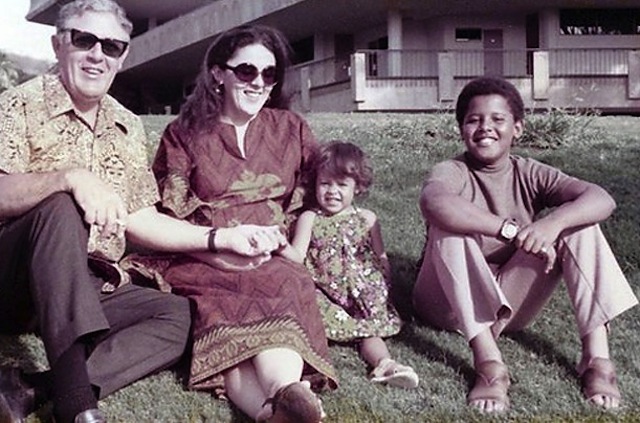

*Photo courtesy of U.S. Embassy Jakarta, Indonesia.

Send A Letter To the Editors