Twenty-five years ago, I was foraging through a museum bookstore and came upon an eye-catching title: AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism. The word “AIDS,” rendered on the cover in large font, seemed more than slightly dangerous in 1988, when so many lay sick and dying and there were no effective treatments on the horizon. Equally attention-grabbing was the book’s cover photograph of of Let the Record Show …, a 1987 art installation in the front window of Manhattan’s New Museum of Contemporary Art by the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP). There, in all its glory, shimmered the iconic SILENCE = DEATH logo, in neon, with a pink triangle perched overhead.

More than two decades later, my copy of the book is dog-eared, the pages loose, with ink-smudged Post-its jutting out from the margins like yellow exclamation points. The book I spied that day has become my bible. It is stuffed with essential texts by activist authors, reflecting the Spock-ish analytical sensibilities of its editor, the art critic and early ACT UP member Douglas Crimp. Among the contributors is medical historian Paula Treichler, who writes of the irrational meanings attached to AIDS, and Jan Zita Grover, who painstakingly defines the “keywords” associated with AIDS, from “carrier” to “risk group.”

For me, the most durable of the essays in the volume is Crimp’s introduction, in which he goads us to stop talking about art of the AIDS era “transcending” the epidemic, as if that would give the work some weird modicum of value. He urges us to stop talking about parlaying art into research by putting it up for sale at AIDS benefits and donating the money to organizations like amfAR, The American Foundation for AIDS Research.

Stop it, Crimp demands. Stop talking about art as a commodity. Instead, start talking about art as a solution to the epidemic itself.

Here’s the most telling passage:

[A]rt does have the power to save lives, and it is this very power that must be recognized, fostered, and supported in every way possible. But if we are to do this, we will have to abandon the idealist conception of art. We don’t need a cultural renaissance; we need cultural practices actively participating in the struggle against AIDS. We don’t need to transcend the epidemic; we need to end it.

In 2004, I traveled to India on a Fulbright and organized a workshop with artists and activists with the aim of putting Crimp’s central ideas into action. In order to do so, my colleagues at the UCLA Art & Global Health Center and I boiled his ideas down to their essence: MAKE ART/STOP AIDS. Over the past decade, we have organized art exhibitions, participatory photography projects, and arts-based sexual health education programs that fulfill the words on both sides of the slash. At every step along the way, we honor Douglas Crimp and his idea that art possesses the capacity to meaningfully intervene in the AIDS epidemic.

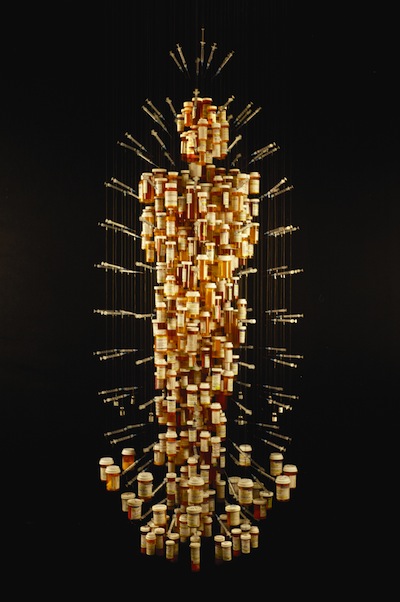

A perfect example is Medicine Man, a mobile sculpture that MAKE ART/STOP AIDS commissioned from San Francisco-based artists Daniel Goldstein and John Kapellas. The piece is constructed of pill bottles that Goldstein and Kapellas, and their partners, saved up from treatment regimens dating as far back as 1985. The artists assembled the bottles in the shape of the Virgin of Guadalupe, with an aureole of syringes arrayed around her body in a halo. You could meditate on Medicine Man for a lifetime, and from it you would learn almost everything you need to know about AIDS, pharmaceutical profits, sexual networks, and our powerful desire to stay alive. When I show people this image, they immediately pick up the spiritual resonances and can see how the artists dissolve the stigma of AIDS in a representation of holiness. But they also see the pain—all those sharp needles—and the privilege, too. That privilege is especially apparent when two lifetime supplies of medication are set side by side with an image by Johannesburg-based photographer David Goldblatt of a South African mother and her two children, who are either too poor to buy medication, or are living with a government too cruel to provide affordable treatment.

Another of our MAKE ART/STOP AIDS projects is ThroughPositiveEyes.org, a website featuring photographs by HIV-positive people living in Mexico City, Rio de Janeiro, Johannesburg, Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., and, most recently, Mumbai. This collaboration with London-based photographer Gideon Mendel is meant to confront the stigma of AIDS by allowing people living with HIV or AIDS to tell their stories, feelingly, in ways that counteract harsh external judgment. One of my favorite photos is Raju’s image of 10 bean sprouts arrayed on a stainless steel plate, each vibrant, growing sprout representing one year of his life infected with HIV—not death, but life.

My students at UCLA understand the power of art to educate, to shift stigma, and to forge powerful channels of communication. They have created a performing troupe, the UCLA Sex Squad, which presents original monologues and scenes to high school students in the Los Angeles Unified School District. Their performances are part of a full-scale public health intervention, designed in collaboration with Timothy Kordic of the district’s HIV/AIDS Prevention Unit. Some 40 percent of high schoolers in Los Angeles will have sex before they graduate; we’re trying to help prepare them for healthy sexual experiences. We’re piloting the program now in Atlanta, Chapel Hill, and Mexico City.

MAKE ART/STOP AIDS demonstrates how art can make things happen in the world, how it can teach and goad and shift and protect us. It’s a reminder, on World AIDS Day, of the most exceptional thing that art can do: save lives.

Send A Letter To the Editors