If you’re wondering why Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders have a shot at representing their political parties in November’s national presidential election, you can thank Theodore Roosevelt.

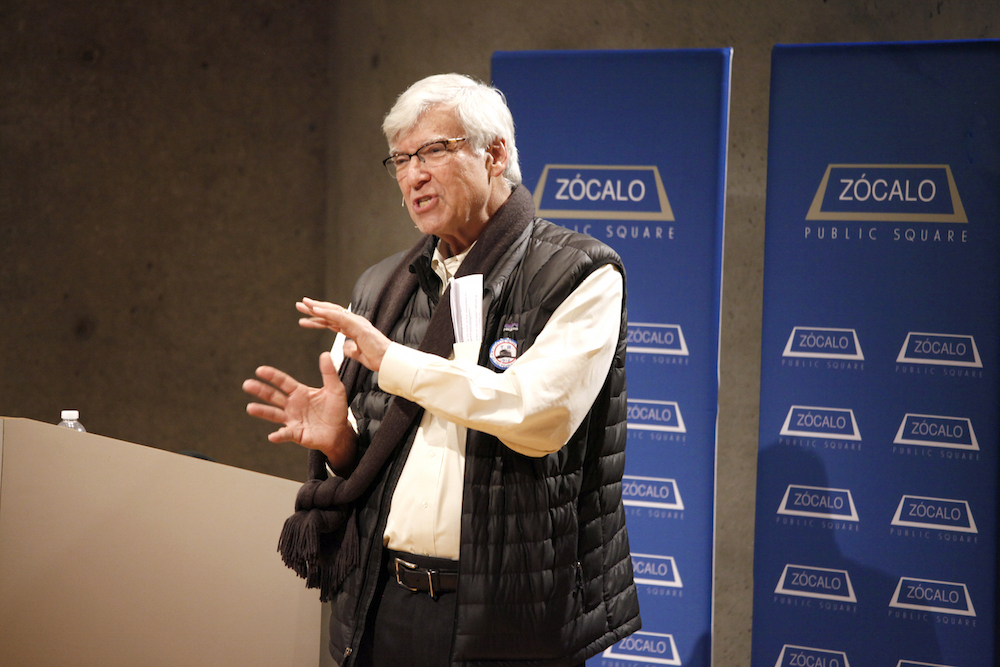

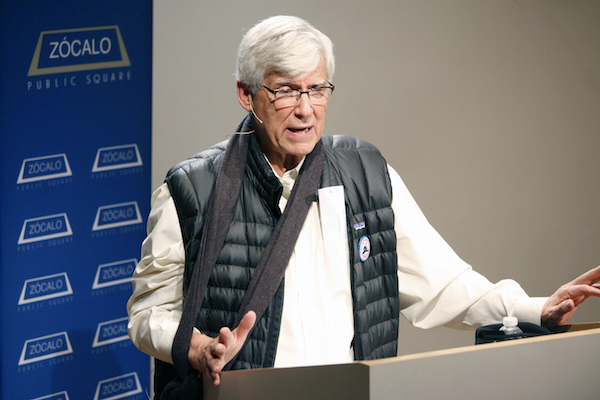

One of Roosevelt’s most enduring impacts was his crucial role in the rise of state-based primary elections, explained Geoffrey Cowan, president of the Annenberg Retreat at Sunnylands, professor at the University of Southern California, and author of the new book Let the People Rule: Theodore Roosevelt and the Birth of the Presidential Primary. He shared lessons from his research with an overflow crowd at a Zócalo event at the Museum of Contemporary Art in downtown L.A. on Friday.

“If the parties today still selected nominees the way they did [before] Roosevelt created these primaries, I think it’s pretty likely that everything would be dominated by party insiders,” Cowan said. “Jeb Bush would probably be the Republican party frontrunner, and Donald Trump wouldn’t be taken seriously. I don’t think Bernie Sanders would be taken seriously on the other side if there were not a chance for the public to participate directly in these decisions.”

Roosevelt had already served two terms as president from the Republican Party when he decided to throw his hat into the ring again in late 1911. Party bosses decided the nominee in the smoke-filled backrooms of political conventions. Roosevelt thought that his familiarity with these men would win him the nomination.

But within months it became clear that his chief opponent William Howard Taft, the incumbent president who had been Roosevelt’s chosen successor in 1908, had locked up the bosses.

So Roosevelt decided that primaries had to be the centerpiece of his campaign. “Let the people rule” became his slogan. He lost the first three primaries in American history in 1912, including one in his home state of New York.

“Humiliated and furious,” Roosevelt started campaigning on the road with vigor, Cowan said. He took a train to Chicago, found enormous success with an “anti-establishment message of reform,” and won the Illinois primary in a rout. “It was the first primary in American history to change a campaign’s momentum,” Cowan said.

By June, he had won nine primaries and thought he had a path to victory. But of course, primaries weren’t the dominant way of choosing a party’s nominee in 1912. Roosevelt still was a long shot—Taft’s men controlled the nomination process and the delegates at the national party convention.

Roosevelt’s supporters set about trying to turn delegates to Roosevelt’s side. Perhaps a large number of African-American delegates from the South might be convinced to switch teams.

Unfortunately, Roosevelt couldn’t capture enough of them. So he went across the street from the convention and announced that he would start his own party: “We stand at Armageddon and we battle for the Lord,” he famously told the crowd.

In one of the more disappointing twists of history, Cowan said, this new party wouldn’t seat any of the black delegates from the Deep South who had switched teams for Roosevelt or the biracial delegations they came with to the Bull Moose convention, opting instead to seat the all-white delegations from those states.

Cowan said he struggled with why Roosevelt made such a decision. Perhaps Roosevelt thought this move would win him some southern states. Perhaps he thought he’d get credit for seating black delegates from the North even if the ones from the Deep South weren’t seated. Perhaps he planned to help blacks once he was in power.

In any case, Cowan said, he considers Roosevelt’s decision to exclude southern blacks as a “stain on his reputation,” and a “disgraceful” example of self-interest and racism.

A half-century after Roosevelt, Cowan himself got involved in primary reform. It was 1968, and Cowan saw a great unfairness remaining in this “mixed” system of primaries and backroom dealings.

In a clip from a black-and-white </a href=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=298X18RnYIQ>ABC news report played for the audience, the newscaster Howard K. Smith talked about how a Yale student named Geoffrey Cowan put together a pamphlet that described how the methods for choosing 600 delegates at the Democratic nominating convention were not even open to the public. That set in motion a string of events, including U.S. Sen. George McGovern of South Dakota leading a commission to write new rules and convince the states to accept them. Eventually the states agreed to a more open process and the newscaster pronounced Cowan as someone “who did more to change Democratic conventions than anybody since Andrew Jackson first started them.”

During the Zócalo event’s question-and-answer session, audience members asked Cowan his opinion on a variety of issues in the presidential nominating process. How does he feel about caucuses? What does he think of a primary decided by national voting rather than going state by state? What does he think about the Citizens United Supreme Court decision, which has made it much easier for money to flow into campaigns? What does he think of the media’s role in elections?

Cowan found much fault with the current system: When people caucus, their bosses could be in the room and sway their opinions. He disagreed with Citizens United that money was the same as speech and both should bear few restrictions. But he also dismissed common reform ideas; a national primary, he said, would benefit those with the most money and the most name recognition.

Cowan left one of his most pointed criticisms for the media. “The press has been almost entirely wrong this season and yet I don’t think the press has a lot of humility about that,” he said.

But Cowan wasn’t sure there were many viable alternatives. “There are problems with every system,” he said.

Send A Letter To the Editors