When I go to an art museum, what I encounter there isn’t always in the brochure. Sure, I enjoy the changing exhibitions. But I’ve discovered museums don’t just offer a feast for the senses; they also offer nourishment for the soul. In allowing us to peer into the mind of someone else, they remind us that we’re not alone in appreciating beauty, that others know sorrow and fear, heartbreak and joy, and that there’s a way to transmute fleeting human experience into something that endures. It’s like therapy—all for the price of admission.

When I go to an art museum, what I encounter there isn’t always in the brochure. Sure, I enjoy the changing exhibitions. But I’ve discovered museums don’t just offer a feast for the senses; they also offer nourishment for the soul. In allowing us to peer into the mind of someone else, they remind us that we’re not alone in appreciating beauty, that others know sorrow and fear, heartbreak and joy, and that there’s a way to transmute fleeting human experience into something that endures. It’s like therapy—all for the price of admission.

For me, the temple that has channeled this divine connection is New York City’s Guggenheim. I was born on the same day it opened—Oct. 21, 1959. Over five-plus decades, I’ve marked the years by my cross-country pilgrimages from the West Coast. In those visits, I’ve seen the direction of my life echoed in the museum’s famous circular design, and my personal story reflected in the titles of abstract paintings—inspired by Chagall and my other favorite artists.

We have a history, the Guggenheim and I.

Homage to the Circle, 1959

On the Guggenheim’s opening day, traffic and crowds clog Fifth Avenue, everyone eager for a first inside look at Frank Lloyd Wright’s audacious creation.

Originally launched in 1939 as the Museum of Non-Objective Painting, the collection had outgrown its previous space, a former automobile showroom on 54th Street. There, the avant-garde paintings that founder Solomon R. Guggenheim began amassing in the 1920s were hung on draperies low to the floor so people could observe them while seated and listening to classical music. From its early days, the Guggenheim provided a full-sensory experience that took people out of their ordinary lives. There was even burning incense.

Some critics pan the new museum’s shell-like structure, claiming its sloped walls make it impossible to display anything properly. One wag dismisses the radical building as “an indigestible hot-cross bun.” Another compares it to a washing machine.

Others declare the Guggenheim a masterpiece, a work of art in itself. Wright, who once called his design a “spiral of life,” died six months before the opening.

While the crowds and critics are making their way through the galleries, I’m born at 2:12 that afternoon on the opposite coast, in a boxy building in downtown Los Angeles that once housed St. Vincent’s Hospital. On my birth certificate, I’m simply called “Baby Girl.”

Square and Circular Forms, 1981

I’m 21, a recent college graduate who’s not too sure what to do with an English degree or where I’m headed in life. My parents take me on a trip to Manhattan, and the Guggenheim is on our list of obligatory tourist sites, like Carnegie Deli or the World Trade Center.

Round where other buildings are square, the museum looks completely out of place amidst the staid skyscrapers. To me, who feels more comfortable with books than classmates, it’s a monument to anyone who doesn’t easily fit in. I love it. Even more as we stroll down the museum’s winding ramp. There’s one—twisting—way forward; you have to trust where it’s going.

At one point, my mother notices me admiring a work by Joan Miró, the Spanish artist who suffered a nervous breakdown in his teens, while working as a clerk. His otherworldly creatures, floating like clouds on the canvas, look familiar. “You liked Miró when you were a child,” Mom explains, and I remember the little book of his paintings I had in second grade. Miró gave up his accounting career to pursue art. Sometimes, finding the right path can be a struggle. I eventually decide to become a writer.

I and the City, 1982-2005

In the years that follow, I return to the Guggenheim whenever I can. I discover mystical Chagalls and lyrical Delaunays. Works such as “Paris Through the Window,” with its curious two-faced man, upside-down train, and soaring parachutist. Or “Simultaneous Windows (2nd Motif, 1st Part),” which makes me feel I’m peering through a stained glass window at something sacred. The museum shows me different ways of seeing. It offers portals to the supernatural. I commune with angels, flying horses, green fiddlers. They teach me that imaginary things can be more real than the parking lots, bland buildings, and other objects outside my office window.

“Paris Through the Window” by Marc Chagall, 1913

On other visits, it’s the more ordinary subjects that mean the most. I’m in my late 30s. My father has just died of cancer. I stop before Picasso’s “Woman Ironing”—from the artist’s blue period. How had I not noticed before these aching shoulders and sad eyes, this emaciated form? But she’s always been here. She’s no different. I’m the one who’s changed.

Later, I learn that the woman hides a secret. In 1989, infrared cameras revealed a painting beneath the painting, an upside-down portrait of a man with a moustache. Who was he, and why did Picasso paint over him? Even art historians are perplexed. It’s a mystery, and I’m discovering life is filled with them—like why people suffer, and why those we love leave us too soon.

Lovers on a White Background, 2006

I’m in my mid-40s and touring the Guggenheim with my husband and another couple. We do everything as couples in those years. Lately, though, my marriage has been spiraling downward. I leave the group to wander through the galleries, alone. Before long, I find myself standing before Kandinsky’s “Composition 8:” His black circle with its cosmic purple orb floats by itself amidst all the sharp edges and broken pieces.

I stare at the painting a long time. After more than 15 years, my husband and I have lost each other. The comfortable, secure life I’ve known is slowly coming apart. I, too, feel like I’m floating. I’m scared I might break into pieces.

Woman Before a Mirror, 2009

October 21, 2009. The Guggenheim and I turn 50. The museum is throwing a big party, and everyone’s invited.

I go with my new boyfriend. We hold hands and take the elevator to the top. The building looks beautiful, like a luminous planet, after undergoing an extensive renovation to repair cracks in its walls. I’ve got a few lines of my own I’d like to erase.

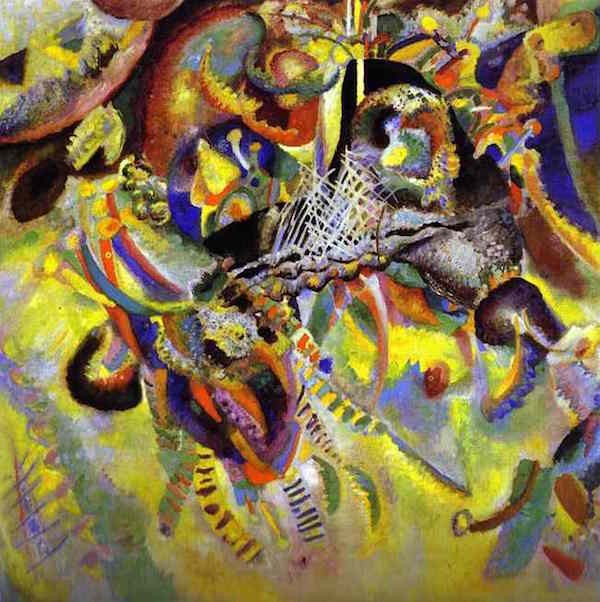

In honor of the occasion, the Guggenheim has staged a major Kandinsky retrospective. We make our way along the curved walls, pausing to study each work. This time, I’m drawn to the artist’s more exuberant compositions, like “Fugue” and “Various Parts.” Their free-flowing shapes dance across the canvases like confetti.

“Fugue” by Vasily Kandinsky, 1914

I have reason to celebrate. I’ve lost a lot of the things I loved since my previous visit—the husband, the house, the kind of friends you accumulate through a marriage. But I haven’t come undone. I’ve grieved and kept going, walking a long ramp one step at a time. Following unexpected curves took me places I might never have ventured on my own and put me in front of visions my own imagination couldn’t conjure up.

Work in Progress, unfinished

Today, as I approach my 57th birthday, I find myself holding a retrospective of my own. The boyfriend and I eventually parted ways. Five years ago, I met my future husband, and after a dizzying six-month romance, we got married in a simple courthouse ceremony.

We talk about taking a trip to New York from our home in Oregon. When we do, we’ll go to the Guggenheim. I’m drawn to its rings like an orbiting moon. I know it will feel timeless and changed. I know it will remind me of where I’ve been and reveal something new about the person I am now.

Divorce or death or simply the day-to-day grind can leave one depleted. But there are places, like the Guggenheim, to reassure us that’s not all there is. The world includes the fanciful, the “non-objective.” Trains can run upside down. Fiddlers can be green and horses can fly like angels. Buildings don’t have to be square.

Sometimes I think about the day in 2059 when the Guggenheim will mark its 100th year. The museum will look as glorious as it did when it opened, and the line of people clamoring to get in will be just as long. Perhaps, if I’m still around, I’ll be there too—an old woman with her many memories. I won’t even take the elevator. Someone will hold my frail hand, and I will slowly make my ascent, moving up the rings toward the museum’s glowing skylight.

The Guggenheim’s skylight

Send A Letter To the Editors