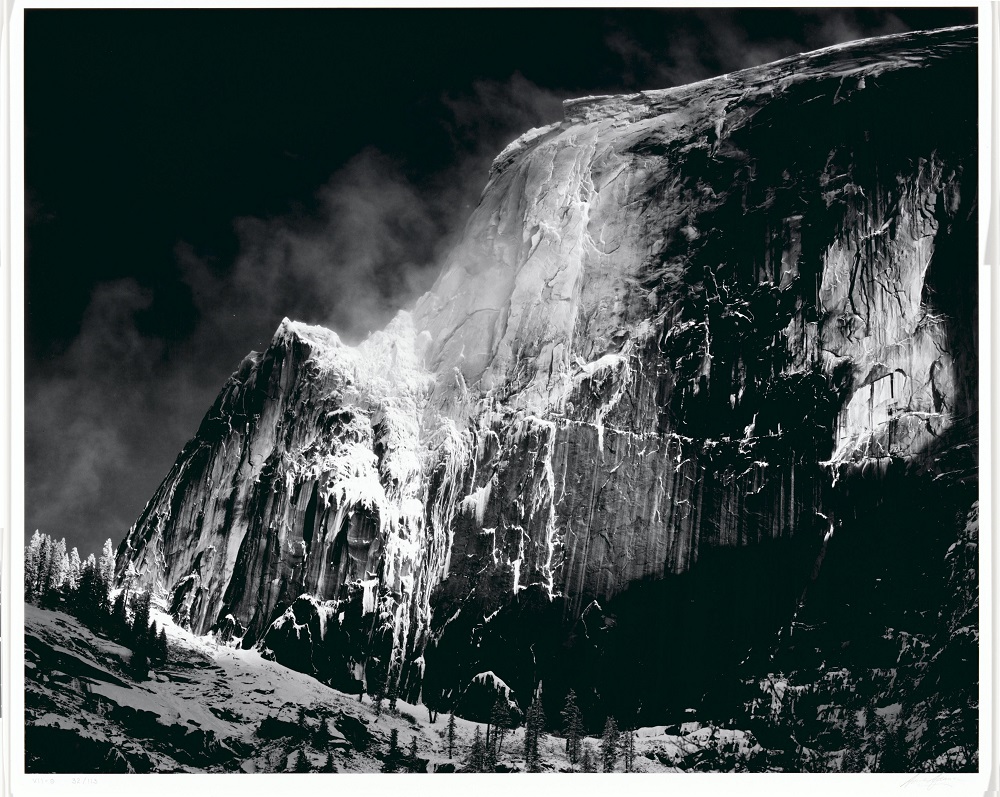

Ansel Adams’ Half Dome, Blowing Snow, Yosemite National Park, is a classic landscape photograph, one that draws upon decades of dramatic imagery touting the far West as the ultimate expression of an expanding American empire.

Ansel Adams’ Half Dome, Blowing Snow, Yosemite National Park, is a classic landscape photograph, one that draws upon decades of dramatic imagery touting the far West as the ultimate expression of an expanding American empire.

It is also a textbook example of what Adams famously referred to as the “Zone System,” a technique that transforms the photographic surface into a study in contrasts. By manipulating the light-sensitive silver within the film and the printing paper, Adams created a gleaming array of ultra-whites, shimmering silvers, and inky blacks—transforming the composition into a formalist study in abstraction and the face of Half Dome itself into a minimalist canvas, with much of the surface area covered in dark tonal variations.

As with a minimalist painting, in which the work is divested of all but the medium’s most essential properties, these deliberately blackened areas represent a scouring of light from the recesses of the picture plane. That scouring, in turn, produces fields of darkness in which the graphic contrasts that are abundant elsewhere in the image all but disappear. By blackening areas of the image to unnatural extremes, he leveraged the combination of mechanical, chemical, and creative elements that comprise the photographic process. As a result, in Half Dome, Blowing Snow, Yosemite National Park, the rocky face of the iconic peak is transformed into a riveting study in graphic manipulation, where what we see most clearly is Adams’ mastery of the medium.

Adams blurred the fine line between notions of photographic objectivity and the artist’s ability to manipulate and obscure. When the Half Dome picture was made (circa 1955), Adams’ reputation as America’s foremost landscape photographer was secure and he was less bound by expectations of accuracy in his images and thus freer to flaunt the creative skills for which he had become famous. This confidence fueled his increasing presence in Yosemite, where his popular workshops helped cement the hegemony of his vision.

Adams’ unabashedly inspiring version of nature became less about the specificities of the place than its role as an abstraction, one designed to evoke intangible emotions over rock and granite. In other words, by mid-century, his photos were relevant in large part because of the widespread willingness to interpret them in aspirational, rather than realistic terms; as dramatic metaphors rather than transcriptions of nature. Highly aestheticized yet entirely accessible, Adams’ work was a response to an elitist New York art scene intent on purging the canvas of references to the visible world, and to the mounting political tensions and anxieties of the Cold War. In Adams’ vision, Yosemite’s granite walls were at once welcoming in their majesty and reassuring in their solidity, a bulwark against both societal snobbery and the specter of capricious, foreign regimes.

Photographic reality is a fragile thing—more dependent on the audience that chooses to see it as such than on the image itself. As his popularity grew and exhibitions of his work attracted larger audiences, Adams doubled down on his vision of nature as a place where clarity of vision powered by graphic extremes and willful omissions widened the gap between perception and reality. These “blind spots” in his photos—as some scholars have termed them—went beyond the tourists, traffic, and trash that Adams is known to have overlooked to include broader changes in postwar American society such as the struggle for racial equality.

Throughout his career, Adams dismissed what he termed “soap-box” art. But his work did not exist in a social vacuum. Rather, at the dawn of the civil rights era, Adams intensified his use of tonal extremes to amplify the metaphorical powers of Yosemite, turning it into a visual ideal that echoed in its aspirational status the more perfect union envisioned when Abraham Lincoln set aside its central valley as a California state park in the midst of the Civil War.

Earlier in his career, Adams had made a rare foray into questions of both social and racial inequality, in his series on the incarceration of Japanese-Americans at the Manzanar camp, titled Born Free and Equal, which drew both criticism and praise for his sympathetic view of its residents as productive, loyal citizens. Thus, while Adams’ take on Yosemite did not overtly confront the political climate, nor did he erase it, embracing the concept of a society improved through a return to its core values.

By 1955, Adams’ darkroom wizardry was producing graphic extravaganzas that promoted patterns of seeing that had little to do with the experience of most Yosemite visitors. As the French philosopher Roland Barthes claimed, a “photograph is always invisible: it is not it that we see.” By the 1950s, Yosemite was a heavily trafficked destination, struggling with a sagging infrastructure and in danger of being “loved to death.” Under increasing demands for novelty, multiple diversions had popped up on the valley floor catering to the growing crowds and diverting attention away from its natural environment. Among these were drive-through, hollowed-out trees in the Mariposa Grove and Camp Curry’s “firefall,” when glowing embers were pushed from overhanging rock to create a dramatic evening spectacle. The gap between such images and the day-to-day reality of Yosemite was thus widely known and impossible to ignore.

But in Half Dome, Blowing Snow, Yosemite National Park, Adams was determined to resurrect the park’s metaphoric might, and along with it a time and a place when the promise of a more inclusive society seemed close at hand.

Send A Letter To the Editors