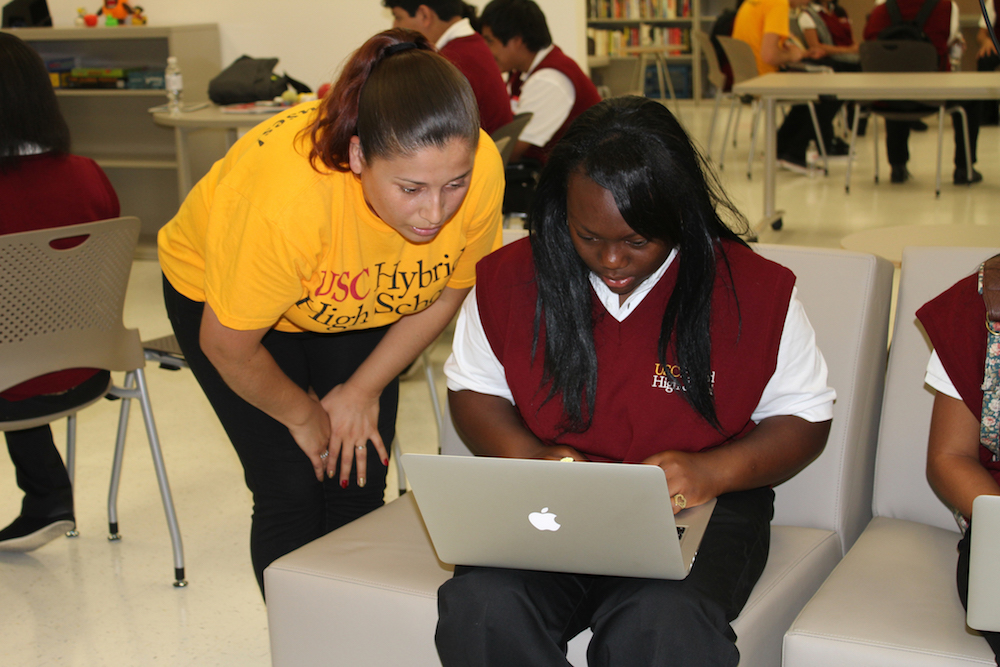

USC Rossier alumna Alejandra Mendoza teaches at USC Hybrid High School.

In 2012, USC’s Rossier School of Education, where I am the dean, began working in South L.A. to improve high school education. Our goals were to help disadvantaged students find a way to college, and, as scholars and educators, to build a school culture from the ground up using high-quality research.

This year, that work has passed a milestone as our first charter school, USC Hybrid High School, graduated its first senior class. All of the students graduated on time and all of them have been accepted into at least one four-year college or university. Many will join the California State University and the University of California networks, and four students have chosen to enroll in the University of Southern California.

This year, that work has passed a milestone as our first charter school, USC Hybrid High School, graduated its first senior class. All of the students graduated on time and all of them have been accepted into at least one four-year college or university. Many will join the California State University and the University of California networks, and four students have chosen to enroll in the University of Southern California.

The road to these successes, however, has not been straight or easy. Indeed, it’s been humbling and instructive to watch how our ideas and research bumped up against competing visions and political realities. We’ve learned through the process how to make adjustments.

For me, the task of helping strong communities build strong children is personal. A devoted mother, a strong church, and a committed school helped push me toward becoming the first member of my family to attend—and graduate from—college. My work at Rossier and with the Ednovate charter management organization (which oversees USC Hybrid High), shares the common thread of trying to improve the quality of education for students, especially for those who need it the most.

Many of the students of Hybrid High—about two-thirds hail from South L.A.—don’t have anything resembling a privileged upbringing. Eighty-five percent of this year’s graduating class qualifies for free or reduced-price lunch. Eighty-one percent of them will, like me, be the first members of their immediate families to go to college.

USC Hybrid High has made progress because students, teachers, administrators, and the community have created a shared vision of making all students college-ready and helping them thrive once they enroll in college. But a unified vision is not easy to achieve, especially in school districts the size of Los Angeles, where each neighborhood has its own identity and its own needs. We learned this early on in our work in South L.A., and it continues to inform our thinking.

Back in 2007, USC Rossier joined the Urban League and the Tom and Ethel Bradley Foundation to form the Greater Crenshaw Educational Partnership. The partnership was part of a broader effort underway to improve the standard of living within a neighborhood of South L.A., and our partnership would focus on the anchor of that area, Crenshaw High School.

At the time, Crenshaw High School experienced problems with student achievement, graduation, and attendance. In the years prior to the partnership, Crenshaw had struggled to keep administrators and improve teaching, and almost 60 percent of students were failing classes.

The L.A. Unified School District saw the partnership as a way to apply outside resources and guidance to a struggling school. As part of our efforts, we enlisted two USC stalwarts: Sylvia Rousseau, a former teacher, principal, and school superintendent who helped lead the school’s administration, including as an interim principal; and Sandra Kaplan, a professor and education consultant. Our USC colleagues in social work, communications, engineering, and business agreed to contribute efforts as well.

LAUSD prioritized student achievement because of the school’s inability to meet the measures of accountability required by federal law. Getting students to show up and stay in school was another priority. But the partnership, while acknowledging those goals, had a larger vision, as did the community around Crenshaw. To change a school requires an understanding of that school, a sustained effort and, above all, stability and consistency. All of those things require time. We recognized that when administrators try to restructure a school around a short-term agenda, like increasing test scores, they risk undermining a school’s culture rather than building it.

The basic problem was this: Just because everyone wants change doesn’t mean they all want the same change. The partnership had thoughtful support and guidance from the school community, including many active parents and teachers. Attendance improved, as did graduation rates. But ultimately, after five years, the district and the partnership didn’t share the same vision and how to get there. And it was too hard to change an existing school without that shared vision.

With that in mind, we worked on building our own school. As USC Rossier began its work establishing USC Hybrid High in 2012, we had the benefit of our experience at Crenshaw, which had allowed us to better understand some themes of school improvement. First, the common purpose of a school must be clear. With USC Hybrid High, we had that: All our graduates will be accepted into college, and at least 90 percent of those who choose to attend won’t drop out.

Second, no school is an island. The community cannot be a passive witness to school improvement. Moving children from kindergarten all the way through to the end of senior year will not guarantee future success if the world they enter has no care, concern, or opportunity for them, so we needed to engage the community, government, and businesses in our work.

Third, equity is important. Years of disaggregating student achievement data shows what many already knew: Opportunity gaps have caused low-income students and students of color to struggle academically. It’s no longer enough to point the problem out—it needs to be addressed, whether the issue involves economic disparities, shortcomings within teaching or administration, or the lack of access to classified school staff members like counselors and nurses.

But even understanding these three essentials, we struggled, and had to make adjustments.

Some issues were more technical than others. We wanted to base the school immediately near our campus, but the cost and availability of space made that impossible, so we ended up downtown in the World Trade Center.

Academically, our model was about using research and technology and great teaching to create individual paths for students, and we planned to be open from 7 in the morning until 7 at night. That didn’t last. Students didn’t need our campuses open for 12 hours—they needed, and their parents wanted, a much more intensive focus on essential curriculum and academics during school hours. And we ended up having to make staffing and teaching changes for this different emphasis.

We also confronted a real problem with disrespectful interactions between students and faculty. And when we tightened up behavioral standards, some members of our first class left by the end of the first year.

There were enough adjustments that we decided we had to go before the L.A. Unified school board and modify our original plan. We had been following the research in our original plans, but we had to make the choices that were right for these kids and for our shared vision. I didn’t like asking, and our changes took some school board members by surprise, but they approved.

Now at Ednovate, our model still combines teaching and technology to tailor experiences to the needs of individual students, with a focus on college prep. Students do the work necessary to be college eligible. As they progress through grades, they receive more autonomy and more chances for self-directed learning, while teachers use data to figure out where students need help.

We’re also determined to make sure that as students choose higher education, they are able to stay. College completion has proven to be an enormous challenge for even the best-prepared students from less privileged backgrounds. To that end, we offer rigorous college counseling, and will continue our advising via dedicated alumni outreach after they graduate. We also are preparing to share our resources electronically with graduates and to be available to help them navigate college environments, including through campus visits.

We think the Ednovate model is now working, and LAUSD agrees—in April, the board of education approved an expansion of the Ednovate network, so that a total of five Ednovate schools will be in operation across the greater Los Angeles area by fall 2017, including in Lincoln Heights, Santa Ana, Pico-Union, and East Los Angeles.

These successes should not be misconstrued. While we benefit from the charter model, a charter school alone is neither a prerequisite for, nor a guarantee of, student achievement. Nor should our students be seen as fundamentally different from students in any other school in Los Angeles. They aren’t.

We think our progress shows the value of research, collaboration, and a commitment to make adjustments in the best interests of students. And we think this kind of work will only benefit future models of school improvement, whether through the new California task force working on improving the state’s school accountability system, or within the Los Angeles Compact, a commitment by 18 major L.A. institutions to support positive change in Los Angeles public schools. USC is involved in both these efforts.

I succeeded in college in part because of the support I received as a student; now, a new generation of students has support from my school and me. One day, we hope these students will support still more students. The work goes on.

Send A Letter To the Editors