Driven. Rushed. Anxious. These adjectives describe me and many of the nearly 4 million people with whom I share the malls, freeways, and surface streets of Los Angeles. Some days, it doesn’t take much to get me agitated; being cut off by a Lexus on my way to work or ignored simultaneously by all employees of a Chick-Fil-A is enough to challenge my belief in nonviolence.

As an antidote to this madness, every year in mid-November, about 20 people from my church, First Lutheran of Venice, drive to Valyermo in the high desert to spend the weekend in another millennium. My church group includes life-long German Lutherans, converted Lutherans, lapsed Catholics, former cult members, and stray humanists who haven’t yet made up their minds about Jesus. We do not agree on every point of doctrine, nor do we agree on political and social issues. What connects us is our belief in a loving God and our need for community.

Our place of withdrawal is St. Andrew’s Abbey, a community of Benedictine monks who operate a non-denominational retreat house where visitors are “welcomed as Christ.” While at the abbey, we live and eat simply, slowly. Whether we speak or keep silent, it is with intention. We leave behind our individual selves and become reunited as a community. We are able to do all this because of the horarium, the daily schedule of the abbey that prescribes specific times for prayer, study, and community.

The monks’ hospitality is genuine, but the accommodations are not opulent. Two low cinderblock structures of 10 rooms apiece house guests, each room containing two twin beds, a desk and chair, a couple of lamps, a temperamental wall heater, and a small bathroom. Given that this is the desert, one might also expect to find some small creature in the room, annoying but not deadly. The majority of our time is spent in the lodge, with its massive stone hearth and abundance of comfy chairs, or walking the grounds of the abbey, awash in the yellows, browns, and reds of fall foliage, the grayish green of cacti and Joshua trees, and the purple of the surrounding mountains.

At most services, the monks sing softly and in unison as a reflection of their sense of community and humility. In a two-week cycle, they will sing all 150 Psalms to acknowledge the Lord’s presence in the natural cycles of life. Psalms are sung on a single note, rising or falling at the end of a line, and ending in a scriptural refrain that changes according to the seasons of the liturgical year. This gives the worship an ancient quality, and connects the singers to all those who have worshiped in this way since the early church.

After Friday night’s supper, we are greeted by Father Patrick, the subprior, who gives a brief history of the abbey for the first-timers and reminds us all of the horarium and the thinness of the guest-quarter walls. Father Patrick was raised Catholic but lost his faith as a young man. Years later, he felt a deep need in his life and came back to the church. After a retreat much like ours, he decided to pursue a vocation and was ordained at the age of 62. His story resonates with our group, many of whom lost faith and returned to it later in life.

The abbey gets very quiet after Compline, the evening prayers. In the years that I have been going to St. Andrew’s, I have succeeded in observing the “Grand Silence” exactly once and, even then, not for the full 12 hours. The purpose of our silence is to hear the voice of the Holy Spirit. It’s not an audible, get-the-straight-jacket kind of voice; it’s more like the voice of a wise mentor or one’s own conscience. This voice gets drowned out in the everyday busyness of life. Being silent for one hour or 12 doesn’t guarantee a profound revelation, but it is another way of slowing down the racing mind and obtaining peace.

As we adjust to the rhythms of the horarium, some of us are unable to unwind from our sea-level lives and appreciate the quiet, worries clinging to us like commercial-grade plastic wrap. It can be good to sit with that discomfort, the knowledge that you are one hot spiritual mess and the fear that everyone else knows it too. On the other hand, sometimes, you have to let your church group members in on the secret, so they can help you haul that trash to the dump.

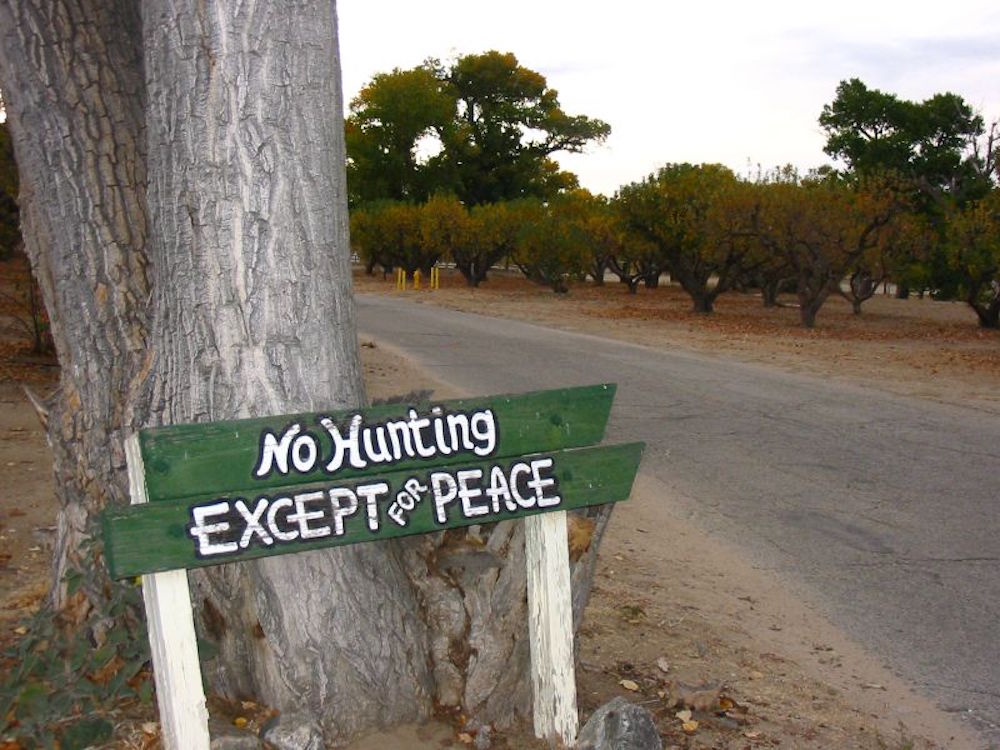

Oblate Cemetery at St. Andrew’s Abbey in Valyermo, CA.

This cleansing begins with a morning service of praise called Lauds. Praise is simply being grateful for who God is, acknowledging his nature as Creator, Father, and Defender. It isn’t asking for stuff; the churchy word for that is “supplication.” The Psalms sung during Lauds are chosen because they address some aspect of God’s character. The final stanza of each Psalm is a variation on the phrase, “In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit,” emphasizing the triune nature of God. As the congregation sings these lines, we rise together and bow as a sign of deep humility.

Our meals are served buffet-style in the large cinderblock dining hall with a vaulted ceiling and full eastern wall of stained glass in an abstract pattern. Breakfast is always eaten in silence, and dinner is silent until after a reading from the Lives of the Saints. The brothers are soft-spoken at all times, so we tend to be so as well. At lunch, the soup is ladled out by Brother Peter, who smiles as though this is an ecstatic oblation.

Brother Peter Zhou Bang-Jiu was professed to the original St. Benedict’s Priory in Chengtu, China. In 1952, after several years of persecution, the Communist regime expelled the European monks from China, closed the abbey, and threw Brother Peter into prison, where he remained for 26 years. He kept his sanity by writing copious amounts of poetry, which he committed to memory for lack of pen and paper. He rejoined the abbey, transplanted to Valyermo in 1984 and has served here ever since. His presence alone is a blessing.

The weekend officially comes to an end on Sunday morning, when we hold a private Lutheran service amid a stand of rustling white Aspen trees planted in 1954. As I drive the hour and a half back toward Los Angeles, I think about Father Patrick, Brother Peter, and all those who have journeyed with me and taught me about living a life of gratitude and humility. The purpose of the desert sojourn is to have intimacy with God, yet I find that I have gained greater intimacy with my fellow church members also. The challenge is to keep these gifts once I leave.

Send A Letter To the Editors