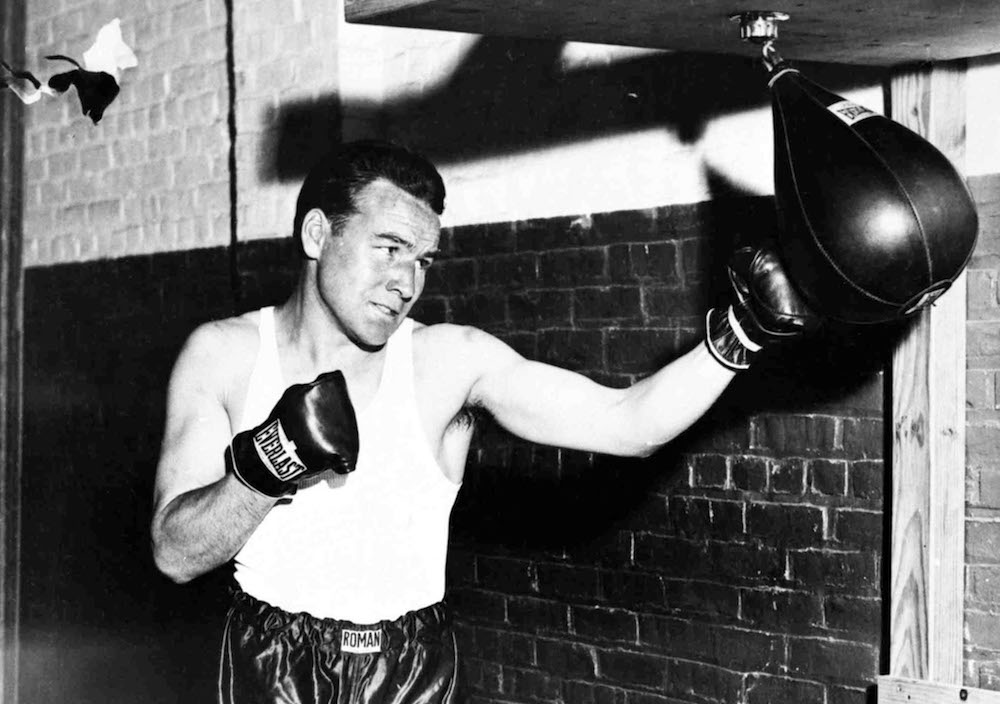

Irish-born American Welterweight boxer Jimmy McLarnin during a traininf session at a gym in America, June 8, 1934. (AP Photo)

Walking along Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles the other day I stumbled across an old acquaintance. On a small bronze plaque embedded into the sidewalk was the name Jimmy McLarnin, alongside a set of boxing gloves. In his prime, in the 1920s and 1930s, McLarnin was one of the baddest welterweights to climb into the ring. A two-time world champ, he fought at a time when the best Irish boxers were routinely pitted against the top Italian and Jewish pugs. His handlers, always eager to build up the gate receipts, dubbed him “The Jew Killer.”

Walking along Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles the other day I stumbled across an old acquaintance. On a small bronze plaque embedded into the sidewalk was the name Jimmy McLarnin, alongside a set of boxing gloves. In his prime, in the 1920s and 1930s, McLarnin was one of the baddest welterweights to climb into the ring. A two-time world champ, he fought at a time when the best Irish boxers were routinely pitted against the top Italian and Jewish pugs. His handlers, always eager to build up the gate receipts, dubbed him “The Jew Killer.”

I’m a sports writer and author, and a longtime admirer of McLarnin’s ring reputation. But by the time I met him for an interview in 2004, not long before he died at 96, age had knocked about six inches off his height, and arthritis had turned his powerful fists into gnarled claws. Age did do him one favor: his “new” claim to fame was that he was the world’s oldest living boxing champ.

Despite an impressive career, McLarnin wasn’t exactly a household name. Which left me to wonder about this mysterious plaque. I’d walked this stretch of the boulevard, through L.A.’s Echo Park neighborhood just north of downtown, countless times but I’d never noticed it.

I quickly discovered McLarnin was not alone—his was just one in a series of similar homages to former sports stars. The plaques are easy to miss. Measuring approximately 17 by 16 inches, about the size of a coffee table book, they don’t exactly pop out of the pavement. Many are blemished with graffiti or dirt. But now that I had noticed them, I set about trying to figure out their relevance to each other and Los Angeles.

My first thought was that the plaques must have some connection with Southern California. McLarnin didn’t fight here, but he spent most of his post-ring career in L.A. This was reinforced when I came upon other greats who made their reputations in Southern California, including Dodgers pitching ace Sandy Koufax, Lakers legend Elgin Baylor, and boxer Armando Muniz. Here also were Pasadena’s own Jackie Robinson, who broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers, and his UCLA teammate, Kenny Washington, the Rams running back who grew up in L.A. and broke the NFL color barrier a year before Robinson integrated baseball.

Olympians seemed to dominate the plaques, which made sense at this local level. L.A.’s dedication to the Olympic Movement runs deep. The city has hosted the Summer Olympics twice, in 1932 and 1984, and is currently bidding for the 2024 Olympics.

Besides track star Jesse Owens—whose triumph at the 1936 Berlin games humiliated Adolf Hitler and his Aryan doctrine—there were plaques for divers Pat McCormick (four gold medals at the 1952 and 1956 Games) and Sammy Lee, the first Asian-American to win Olympic gold (1948, 1952); 1960 decathlete gold medalist Rafer Johnson; 1968 pole vault winner Bob Seagren; swimmer John Naber, a five-time Olympic medalist; Frank Lubin, who helped the U.S. win the first gold medal awarded in basketball in 1936; and sprinter Wyomia Tyus, who won back-to-back gold medals in the 100 meters (1964, 1968).

Bronze plaque on the Avenue of the Athletes in the Echo Park neighborhood of Los Angeles.

But I also noticed several outliers, like Babe Ruth and Joe Louis, icons both, but athletes with little connection to L.A. In search of an organizing principle, some rhyme or reason for this esoteric boulevard of bronze, I turned to Fred Claire, the former general manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers, who immediately knew what I was talking about.

Claire told me that a local entrepreneur by the name of L. Andrew Castle dreamed up the entire endeavor, dubbing it, grandly, the Avenue of the Athletes. Castle originally came to Southern California to work with Charlie Chaplin at Essanay Film Manufacturing Company, one of the pioneering silent-movie studios on the West Coast.

Castle left motion pictures for photography and, beginning in 1944, taught the craft at what was then Loyola University-Marymount College. He served as a team photographer for the Dodgers after the ball club moved to L.A. from Brooklyn in 1958 and worked for the Tournament of Roses and their annual New Year’s Day parade in Pasadena.

Castle owned two camera shops, one in Echo Park and one in Hollywood, back when photographers used film, which had to be processed and developed in darkrooms. He couldn’t help but notice that the Walk of Fame along Hollywood Boulevard, which officially launched in 1960, was attracting tens of thousands of tourists to an area that had little actual connection to movie and TV stars beyond the name “Hollywood.”

Claire told me that Castle envisioned an Echo Park version of the Walk of Fame, but for athletes instead of celebrities. In the mid-1970s, Castle persuaded the city of L.A. to grant him the permits to launch the project. He rallied support from neighborhood merchants, the Echo Park Chamber of Commerce, and the Dodgers, who were now comfortably ensconced in their own stadium in nearby Chavez Ravine.

A selection committee was formed, and the first set of bronze plaques was laid in concrete in 1976. The committee met for organizational lunches at Barragan’s, a now-closed Mexican restaurant located a couple blocks from Castle’s camera store. But when Castle died in 1978, followed almost immediately by his wife, enthusiasm for the project faltered.

In October of 1985, four new bronze plaques were installed, honoring basketball great Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, tennis star Billie Jean King, Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda and, posthumously, Castle himself, bringing the total number of inductees to 32.

But that was the end of it. This bit of inconspicuous streetscape never found its footing, and is all but forgotten today. “Did the Avenue of the Athletes fulfill Andy Castle’s dream?” Claire asked. “No, but at least he had a dream.”

Today’s Walk of Fame, by contrast, includes more than 2,500 stars along a 15-block stretch of Hollywood Boulevard (and several blocks of Vine Street). In a nation fascinated by fame and celebrity, we want to touch the legends and we want contact with their achievements—even if it’s with the soles of our sneakers.

That accounts for legions of imitators the Walk of Fame has spawned—including, of course, Castle’s Avenue of the Athletes—as well as the hundreds of halls of fame that have opened their doors across the nation. It’s worth noting that Walk of Fame stars, or their representatives, must now pony up $30,000 for the privilege of being included. Call it the price of fame.

Alas, no one emerged to carry Andrew Castle’s torch in Echo Park. Even so, the very reason that Castle thought up the concept—to boost foot traffic in a downtrodden area—happened eventually and somewhat organically, spurred by a housing boom that has brought with it vegan bistros, craft brew pubs, artisanal coffee shops, and the requisite anti-gentrification outcry.

The plaque that honors Andrew Castle still rests outside the former location of his shop on Sunset Boulevard, diagonally across from Jimmy McLarnin. Castle’s marker features a boxy camera of the sort that photojournalists used in the 1950s and 1960s—it resembles an old Rollieflex—which is entirely appropriate given that his contributions to photography may well outlast his quirky, quixotic mission.

Up the street from the Avenue of the Athletes, inside Dodger Stadium, the team has established an annual award in Castle’s name for the best photo of the season by a local professional photographer. The winning pictures are displayed outside the press box.

Send A Letter To the Editors