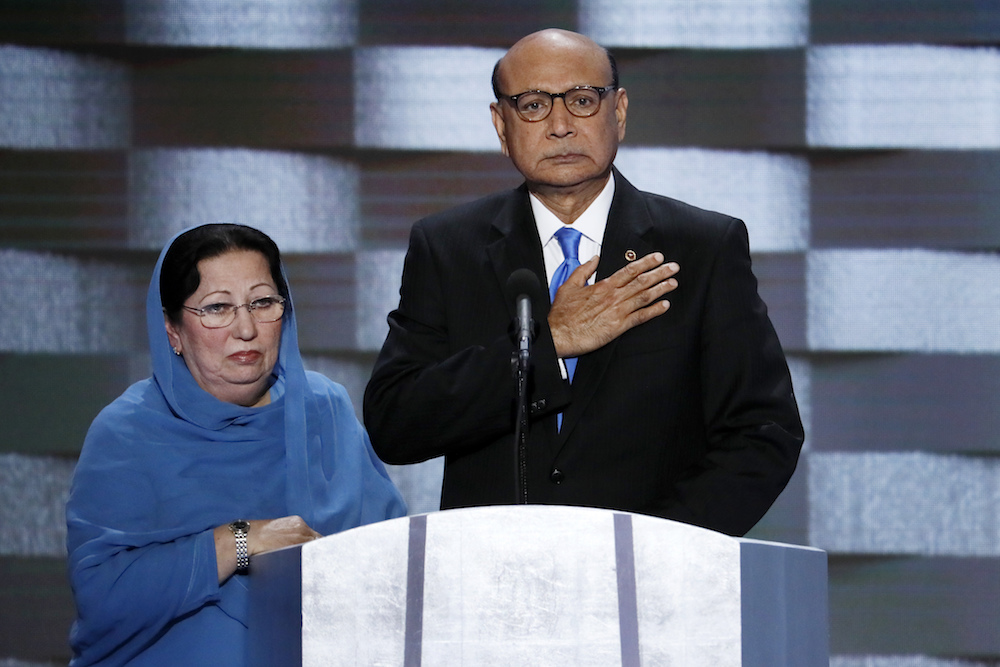

Khizr Khan, father of fallen US Army Capt. Humayun S. M. Khan and his wife Ghazala speak during the final day of the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia , Thursday, July 28, 2016. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Much like today, the 1910s and 1920s were a time when the fear of immigrants convulsed American society.

At the time, the world was reeling from geopolitical instability and economic recession. Terrorists calling themselves anarchists were using bombs against their antagonists in the United States. Foreigners—Jews, Catholics, Christian Orthodox from eastern and southern Europe, and East and South Asians from Japan, China, and India—were thought to be polluting America with their religions, cultures, and radical ideologies. That these immigrants formed a large portion of the population—similar to now—heightened fear of their presence and its effects.

The Republican Party, back in power in 1921 after an eight year absence, resolved to—and did—close America’s gates to immigrants from the world beyond the western hemisphere. The GOP had the support of the southern wing of the Democratic Party, in which nativist sentiments also were running strong. The Ku Klux Klan was revitalized in both South and North, drawing millions of members and placing Jews, Catholics, and African-Americans in its crosshairs. When Irish-American Catholic Al Smith ran for president as a Democrat in 1928, he was mercilessly attacked for his alleged subservience to the Pope.

The charges leveled at eastern and southern European Jewish and Catholic immigrants were every bit as harsh as those directed by Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump at Mexicans and Muslims today. The European immigrants of yesteryear were accused of being prone to violence, of having no regard for the traditions of liberty and democracy that Americans held dear, of being made of inferior racial stock, and of being incapable of becoming good Americans.

In 1924, Republican Congressman Fred S. Purnell of Indiana stated on the floor of the House of Representatives that “there is little or no similarity between the clear-thinking, self-governing stocks that sired the American people and the stream of irresponsible and broken wreckage that is pouring into the lifeblood of America the social and political diseases of the Old World.”

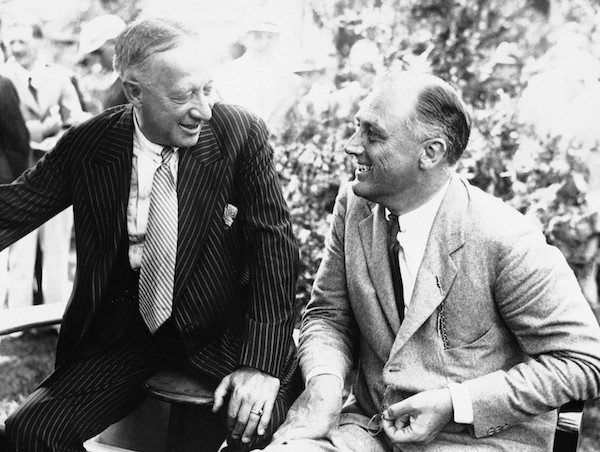

Purnell and his supporters won big, yet, the attacks on the racial and moral character of the newcomers roused millions from political quiescence. New immigrants and their children began to declare that America was their home, too, and that they would build a country free of intolerance. They naturalized and registered to vote in large numbers. They chose congressmen, senators, and governors from the Democratic Party’s northern wing, in immigrant-rich states such as New York and Illinois, as their tribunes. While their vote totals were not large enough in 1928 to save Al Smith from defeat, they became a critical part of the coalition that swept New York Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt into the White House in 1932 and three times thereafter, making the Democratic party and liberalism the dominant forces in American life for 40 years.

Richard Nixon’s election in 1968 challenged the liberal dominance that New Dealers and the new immigrants had forged, but only Ronald Reagan’s triumph in 1980 upended it. By then, the Republican Party had spent two generations in the political wilderness. The descendants of the new immigrants counted themselves, and were counted by others—including Reagan—as the best of Americans. In the process of making a home for themselves in the United States, these groups transformed America from an Anglo-Saxon outpost to a cosmopolitan Judeo-Christian civilization. That change may appear limited by today’s standards; but those fighting for it then faced opposition as fierce as a campaign to turn America into an Abrahamic-Christian civilization would confront today.

Once again, America is divided between those who think that the virtue of an older and narrow America should be restored and those who believe that newcomers can enrich America with their work and creativity. Trump leads the restorationist camp. He has denounced Mexican immigrants as rapists. He has pledged to deport 11 million undocumented immigrants. He has declared that a well-qualified judge of Mexican descent, whose family has been here since the 1920s, is incapable of rendering an impartial ruling in a case involving the alleged misdeeds of Trump University. Trump also wants to outlaw Muslim immigration, much as his predecessors in the 1920s banned eastern European Jews and Italians for being mortal threats, both ideological and physical, to the American way of life.

Irish-American Catholic and Democrat Al Smith (left) lost his 1928 presidential bid, but a surge of immigrant support helped sweep Franklin Delano Roosevelt (right) into the White House in 1932.

One day, Trump may be remembered for giving today’s immigrants the motivation to bust into the political process, to be counted as Americans, and to define an America that they can call their own. His poll numbers among Latinos are barely in double digits at a time when it has become virtually impossible to win a presidential election on the basis of the non-Hispanic white vote. We don’t know how large the Latino mobilization will be on election day, although nearly three quarters of Latinos report being “highly interested” in the outcome, a rise of nearly 50 percent over the equivalent figure in 2012.

The GOP establishment is deeply concerned about the party’s unpopularity with Latinos, and what it means for its long-term prospects as a governing party. That’s why it commissioned a post-mortem of the 2012 presidential election that called for Republicans to embrace a different tone, and a different set of policies, to woo America’s fastest-growing demographic. But Trump has a very different agenda, and his politics of racial resentment may yet deliver a razor-thin, backward-looking victory in 2016. And yet, the example of the 1920s and 1930s demonstrates the long-term risk entailed in arousing the long-term ire of tens of millions of actual or potential voters.

That Trump has provoked such ire became startlingly clear in the Democratic National Convention speech given recently by Muslim-American immigrant Khizr Khan. After extolling America for the blessings it had bestowed on him, his wife, and his three sons, Khan rebuked Trump for not knowing the Constitution and for sacrificing “nothing and no one” to defend American ideals. Khan spoke of his son, U.S. Army Captain Humayun Khan, who had given his life fighting for America in Iraq. “If it was up to Donald Trump,” Khizr observed, Humayun “never would have been” allowed to immigrate to the United States or to serve in its military. Khizr implored “every patriot American, all Muslim immigrants, and all [other] immigrants … to honor the sacrifice of my son, and on election day take the time to get out and vote.”

Consciously or not, Khan was standing on the shoulders of the immigrant generation of the 1920s and 1930s. That generation and their descendants showed an unexpected capacity for political mobilization, and for using the political power they thereby acquired to punish the purveyors of anti-immigrant bias. Their example reminds us how immigrants battling for their rights is one of the best ways to deepen their attachment to America; and that American democracy can deliver on its promise: namely, to give voice to the “tired and poor yearning to breathe free,” and to allow them a hand in shaping the politics and culture of their land.

Send A Letter To the Editors