Ed Ruscha is expected to reappear in Los Angeles this summer, after having been absent for a decade. Ruscha is the artist who famously didn’t leave, when leaving L.A. for New York became the conventional career move. But Ed Ruscha the artwork is gone. A youthful, fleshy Ruscha, 70 feet tall, casually posed, painted by the muralist Kent Twitchell in 1987 on a wall overlooking a parking lot on Hill Street, was painted over by government contractors in 2006. The loss of Twichell’s Ed Ruscha Monument became the subject of an important court decision on the rights of artists and their works.

Twitchell has announced plans for a new Ruscha mural, on the blind wall of the third and fourth floors of an art district hotel, not far from a popular sausage and beer restaurant and the new sales rooms of the Hauser Wirth & Schimmel gallery. Ruscha is now 78, and it’s his older face, leaner, more knowing, that will look over downtown’s askew street grid. Ruscha will appear to lean his elbows at ease on the roof of an adjacent building, his large hands prominent. They are the hands of a man who makes things with them.

These things—paintings, prints, photographs, collages, films, and artist’s books— have been coming from Ruscha’s hands since the early 1960s. Most critics locate this work somewhere between pop art (because, Ruscha says, he listens to L.A.’s “crass commercial noise”) and conceptual art (because some of it is made on order to a set formula). What Ruscha does, however, is neither pop nor conceptual. There is an art of being in Los Angeles, and that’s what Ruscha does.

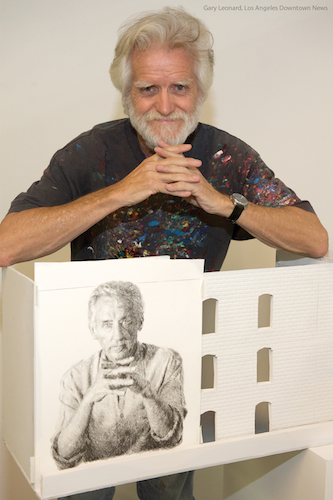

Muralist Kent Twitchell with the mural he plans to paint of artist Ed Ruscha on a building in downtown Los Angeles.

Being in L.A., despite the stereotype of its laidback life, isn’t easy. As Ruscha shows, the city is sketchy, repetitive, too brightly lighted when it isn’t shadowed, and flat. He once told interviewer Gary Conklin, “It’s all façades here—that’s what intrigues me about the whole city of Los Angeles—the façade-ness of the whole thing.” The city’s two dimensionality—a quasi-desert’s grand but withholding vista—is in Ruscha’s 25-foot-long panorama, Every Building on the Sunset Strip and in his absurdly expansive landscape paintings with their wide-screen, Panavision aspect ratio. In L.A.’s light, as Ruscha captures it, things may be startlingly present but nothing is near enough to embrace.

In some of those panoramas, a line of text, small and paralleling the horizon, advertises a desire or eavesdrops on a fear to which the setting is indifferent. That indifference, in another context, used to be called the romantic sublime. Los Angeles can’t be sublime (although it evokes terror among some observers). For one thing, L.A. is too much fun. Ruscha’s apocalyptic, funny Hollywood isn’t 19th century landscape painter Frederic Edwin Church’s Cotopaxi, despite their similarities. The Hollywood sign is forever part of the conversation about the way we amuse ourselves. Other than that, he once said of the sign, “It might as well fall down.”

That’s Ruscha the deadpan humorist, craftsman of American-style Dada, accepting things at face value, even the most blatantly inauthentic, and in the process articulating what it means to see Los Angeles. Here, where much merely seems, actually seeing is an achievement. It’s also defiance. In the bleak, monochromatic paintings Ruscha called Metro Plots, where the grid of Los Angeles is rendered obliquely and as if from the air, the street names almost fade into the ashen background, but not quite. This landscape of erasure “could almost be thought of as, well, after the holocaust,” Ruscha told Christophe Cherix of the Museum of Modern Art in 2012, “or … somewhere down the line in our very deep future.” And yet, after the disappearance, by catastrophe or time, of every building on every boulevard of Los Angeles, something would remain. The stubborn facticity of the specific—its resistance—will linger. Ruscha’s conviction (not always firm, however) that something of transient, flimsy Los Angeles persists is his purest gift to being in L.A.

Ruscha’s off-kilter take reappeared in the series of paintings he called City Lights, in which the mercury vapor lamps of decades ago, their white glare making the darkness darker and washing out all details, line streets that diagonal into the edge of the frame.

That kinetic perspective—of something emerging and passing the observer—fascinates Ruscha. To be in Los Angeles is to want to be in motion. It’s part of the thrill of the Standard Station paintings, as well as Norm’s, La Cienega, on Fire, and the Hollywood studio logo in Large Trademark with Eight Spotlights.

Ruscha ties this desire to the film cliché of a speeding train entering the frame, growing larger, and crossing the screen diagonally. “That was kind of cosmic to me; and I felt … there was something sweet about it. It was a sweet spot in my thinking,” Ruscha told MOMA’s Cherix.

Cinematic diagonals animate other works: the heavenly lights of the Miracle drawings, the shaft that cuts through Picture Without Words, and the movie projector light that casts “The End” in The Long Wait.

To be in Los Angeles juxtaposes the dream state of movie watching with the materiality of filmmaking, not just with the disenchantments of the film industry but also with the scratches and skips in a movie while it’s being shown. Those errors are visual junk but important to Ruscha because they reposition the viewer in the present while reminding the viewer that each print has its own history. Angelenos may appear to be immune to history, but Ruscha isn’t. He’s blotted reprints of his Sunset Boulevard photographs from 1966. He drew similar marks through another version of “The End” in Scratches On Film. And he painted a gallery of Western movie icons as if the buffalos, wagon trains, and teepees were grainy silhouettes on decomposing nitrate film stock. The fate of marginal things interests Ruscha, prompting him to re-photograph the commonplace boulevards he first documented in the mid-1960s.

Ruscha arrived in Los Angeles in 1956, when he was 18, when the city was just as adolescent and full of new things for a kid from Oklahoma. They were “modern, sleek things,” Ruscha remembered, and “very jazzy to me, and I thought that was like some kind of new music.” The cognitive dissonances of the city gave his work the conflict he was looking for. The heroism of the city’s unremarkable, persistent things has given the work its poignancy. The steadiness of Ruscha’s gaze at the city—the integrity and moral weight of his observation—gives us the art of being in L.A.

Send A Letter To the Editors