“There be monsters here,” old maps warn, of oceans as yet uncharted. But there are monsters even in well-trodden territories.

Let’s start with the blade-wielding clowns lurking in American woodlands (And not only there: One even showed up in my adopted hometown in rural Slovenia). Yes, I know that this is a fad, stoked by over-enthusiastic fans anticipating the new film version of Stephen King’s It, but it is outrageously creepy. Citizens are fleeing in terror and calling the police, and evil clowns are being arrested.

Monsters might be scary, but we humans need monsters—because they are far less frightening than the unknown. Our need isn’t new; it has been a consistent characteristic of humans since time immemorial. The recent discovery of a lost 16th century illustrated manuscript filled with illustrations of mythical apocalyptic beasts, now known as “The Book of Miracles,” is a case in point.

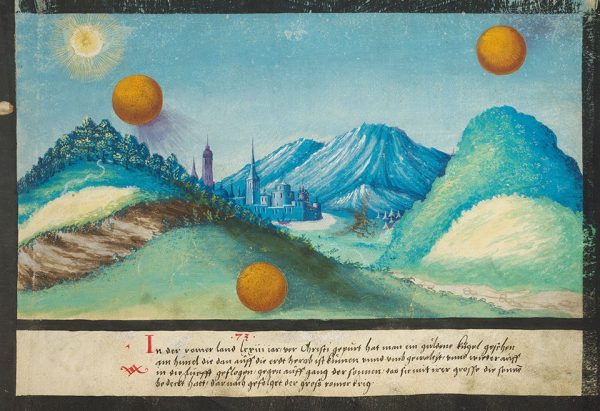

73 BC, Golden balls.

The near-vanished manuscript came to scholarly and popular attention when it was auctioned in 2007 in Munich to British fine art dealer James Faber. In 2014, Taschen released a facsimile of the book, presented in an artfully designed box. The original, whose author and illustrator are unknown, was published in 1550 in Augsburg, Germany and contains 169 strange, wonderful, and monstrous watercolor and gouache illustrations. They depict purported miracles of the natural world, with strong reverberations from the “Book of Revelation,” with its descriptions of allegorical monsters.

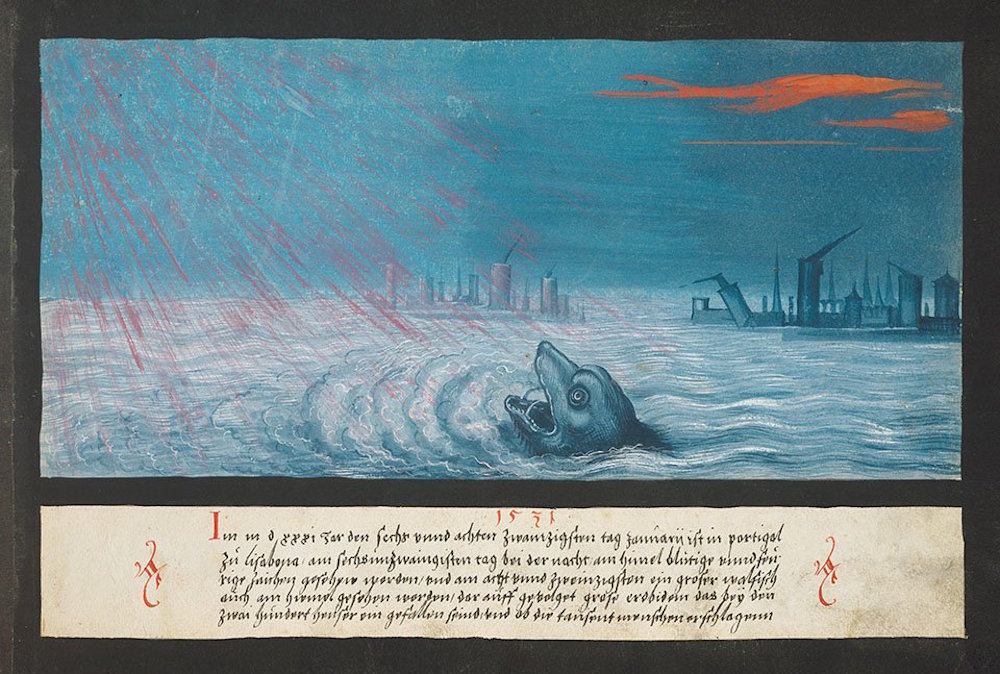

1496, Tiber monster.

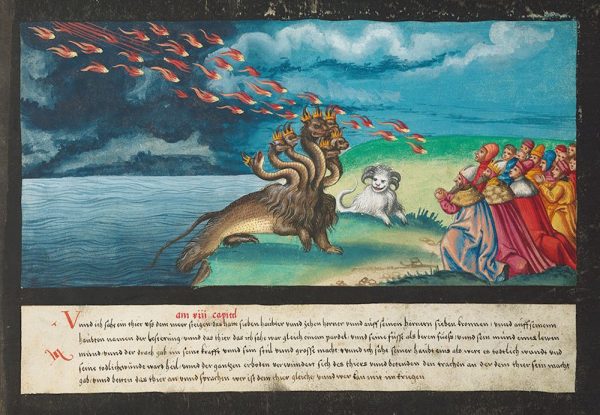

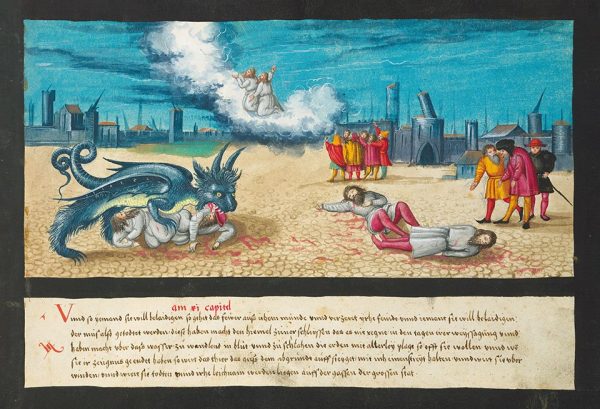

In “The Book of Miracles,” the First Beast of Revelation, for instance, is an ocean-dweller with seven heads and ten horns, the feet of a bear, the mouth of a lion, and the body of a leopard. The Great Dragon also has seven heads and ten horns—and a tail that can sweep a third of the stars out of the sky.

It is revealing that “The Book of Miracles” focused on the supernatural at a time when Europe was ripe with all too real monstrosities: Plague, war, lawlessness, massacres, bloodshed between Protestants and Catholics. Perhaps there was some combination of comfort and escapism in shifting focus from the imminent dangers at the door to otherworldly signs and wonders.

The sea monster and the beast with the lamb’s horn.

Of course, these monsters were plausible concerns for some of the contemporary populace. The manuscript provides what appears to be a “factual” account of reported miraculous events: A sort of 16th century eyewitness bestiary, with dates and locations, and an artist’s strikingly modern interpretation (if you had told me these were painted by Rousseau, I might have believed you).

1533, Dragons over Bohemia.

We have, for example, a 1496 appearance of the “Tiber monster” shown with the torso of a woman, a bearded man’s head for a rump, the right leg of a horse, the left leg of a rooster, a dragon-headed tail, and what looks like a kangaroo’s head (though the historian in me is guessing that it’s not). A 1531 earthquake at Lisbon is depicted as a whale (though it more closely resembles an angry seal) emerging from billowing blue-white waves. In 1533, it seems that a swarm of snake-like dragons was spotted over Bohemia, while several undated creatures are also featured, including a “sea monster and beast with the lamb’s horn” and a “beast from the bottomless pit,” both likely drawn from Revelation (though it’s tough to tell: I’m pretty sure the biblical sea monster had seven heads and ten horns).

The beast from the bottomless pit.

You may have sensed a theme. Monsters of old are not created wholesale from scratch, but are patchworks of existing, real creatures sewn together like Frankenstein’s creation. This method echoes Hieronymus Bosch’s famous hellscapes, populated by hybrid human-animal or multiple-animal creatures. And it is part and parcel with Freud’s theory of the unheimlich, or the uncanny—beings or beasts or places that straddle the boundary between two opposites, a liminal zone, part of the dream world, part of the real.

Celestial swordsman, castle and army over Strasbourg.

We like to think of ourselves as so enlightened that monsters have become our playthings. But the truth is that we need them. Even today. Perhaps not as we once did, but as an integral part of how we process life, and particularly the bad things.

Consider how much easier it is to think of modern human monsters, like Hitler or Stalin, as two-dimensional cartoon super-villains—so evil we don’t even consider humanizing them by thinking of them as people with feelings and origins, cuddled by mothers and teased by schoolmates, maybe, until evil grew from decency. It is easier to pen them up, dismissing them as outliers and inhuman monsters, than to admit that they are just a hair’s breadth away from us.

Send A Letter To the Editors