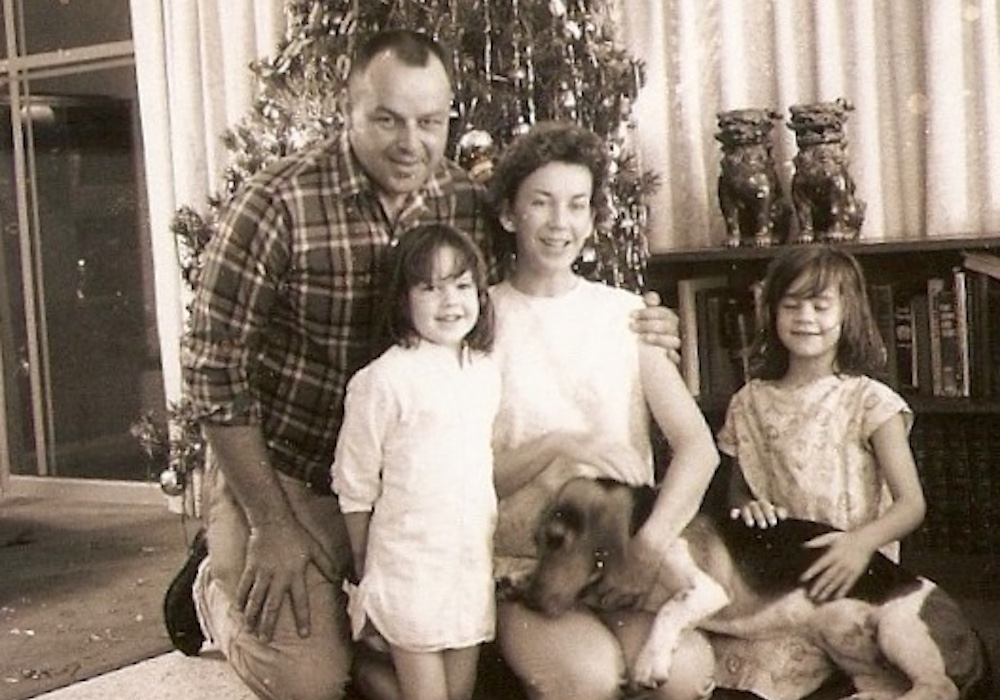

The author and her family when they lived at Homestead Air Force Base, two years after the Cuban Missile Crisis. The author is on the right. Courtesy of Karen Bjorneby.

On a Tuesday morning in mid-October 1962, my father received a phone call ordering him to fly from where we lived, Richards-Gebaur Air Force Base outside Kansas City, Missouri, to Grand Island, Nebraska. He had to leave immediately. He couldn’t tell my mother why, but he did tell her that the president would speak later that night on television, and that she should listen.

On a Tuesday morning in mid-October 1962, my father received a phone call ordering him to fly from where we lived, Richards-Gebaur Air Force Base outside Kansas City, Missouri, to Grand Island, Nebraska. He had to leave immediately. He couldn’t tell my mother why, but he did tell her that the president would speak later that night on television, and that she should listen.

My mother didn’t need to hear anything more. As soon as he left, she bundled my sister and me into our white Chevy station wagon and drove to the base commissary. I was not quite five years old, my sister not quite three. At the commissary, my mother filled two grocery carts with food, candles, matches, batteries, and propane for the camp stove.

My father flew fighter-interceptors, meaning that if Soviet bombers carrying nuclear weapons were headed toward the United States, it was his job to intercept and destroy them because a nuclear blast at altitude would cause less damage than a ground hit. I was still young enough to form a mental picture of him as Superman, flying fast into space to smash bombs with his fist, reeling back from explosions but then shaking himself upright and flying safely home. I was too young to ask what a nuclear blast would do to him and his plane, but even when I was old enough to ask I didn’t.

The Cuban Missile Crisis now seems like ancient history, but Cold War hostilities shaped my life and the lives of many others who grew up pricking with a constant sense of threat, which stern codes of silence demanded we never speak of. That silence was deepened in families like mine: An Air Force film for children taught us to be wary of questions, even from friendly teachers, when small bits of home life could, for a spy, add up to classified information. Such a code of silence now, in an age when everyone shares every feeling on Facebook, seems as surreal as a 9-megaton bomb. Such wariness seems absurd in an era when former missile sites have been converted into picnic spots.

The author’s father near the cockpit of his F4. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, he flew an F102. Courtesy of Karen Bjorneby.

That autumn day in 1962, my mother pulled our station wagon, brimming with provisions, into the carport. Our neighbor was outside, in red lipstick and black stretch pants, smoking a cigarette and watching her two sons play around a tree. She came to help with the groceries, and when my mother asked if her husband, too, had gotten a call, she laughed. She wasn’t worried, she said; it was all just posturing. And if not, she shrugged, we’d all be dead anyway. So she wasn’t preparing for anything except Halloween.

My mother packed our countertops with Saltines and Spam, cookies and peanut butter, canned soup and canned vegetables. In the basement, she made up sleeping bag-beds and filled Coleman jugs and spare canteens with water. That night, the president appeared on television and matter-of-factly explained that the Soviet Union was installing nuclear missiles on Cuba, and that this crisis might lead to war.

We settled in to wait. For two weeks, my mother kept my sister and me close, doing her best to cheer us. She spoke to no one, because she couldn’t risk answering anyone’s questions; she couldn’t let on that my father was involved in the crisis or tell anyone where he was.

My parents had been married for eight years by then. That they came together is an American story in itself. My father was a boy from Ketchikan, Alaska, where his grandfather had been the sheriff, and my mother was a girl whose parents had traveled back and forth from Tampa to Detroit looking for work, and who’d won a scholarship to college in Texas. She met my father in Big Spring, at an Elks Club party where she taught him to dance to the song, “Put Your Little Foot.” He was tanned and tall—nearly too tall for cramped cockpits—with extraordinary peripheral vision and the controlled aggression and high tolerance for pain and fear the Air Force then selected for in their pilots. And he was a jokester, a man who subscribed to both Mad Magazine and Scientific American.

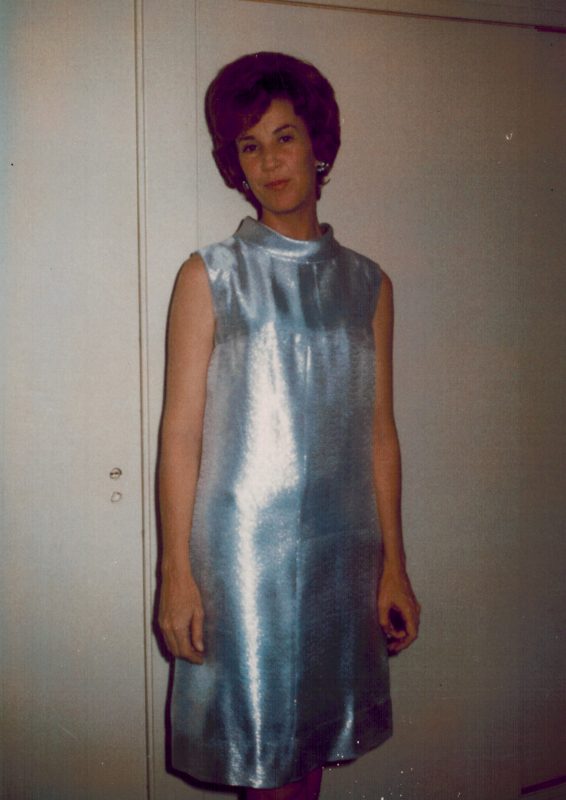

My mother was a willowy redhead, her flirtatious charm covering an iron resolve borne of a Depression-era childhood etched by poverty and hunger. When my father was gone, she kept the car in repair, the taxes paid, and the furnace going. Whenever she could, she helped other wives cope. And she was a crack shot—never would she choose preparing for Halloween over striving to survive.

That same day, inside a few military hangars at a small-town airport in the plains of Nebraska, my father was helping rack nuclear missiles onto fighter jets, his included. Then he flew to Homestead AFB, thirty miles south of Miami. As he entered Florida airspace, he said later, the view on his radar screen was like nothing he’d ever seen before. The entire state seemed to vibrate; so many planes were flying in, it looked like a beehive, swarming with nuclear-armed aircraft, all prepared to obliterate Cuba.

What was strange to me then was the sudden silence on the base. All my life, we’d lived less than a quarter mile from the flight line, so that my father could get to a plane in fifteen minutes. I’d grown up with the sound of engines in my ears, with the crack and thunder of a fighter breaking Mach I overhead. Each night I fell asleep to jet-whine, like a lullaby. But now, all was quiet. I slept badly. I was too young to understand the crisis, but I wasn’t too young to know that if the planes weren’t flying, something was wrong.

Not one of those nuclear-armed aircraft ever took off toward Cuba to unleash Armageddon. President Kennedy negotiated an end to hostilities by agreeing to remove American missiles from Turkey in return for the Soviet Union removing their missiles from Cuba.

The author’s mother in the mid-1960s. Courtesy of Karen Bjorneby.

The crisis ended, my father came home, and we all feasted on moon pies. Our house was an abundance of loving gratitude and relieved laughter. But throughout the days of waiting, my mother had worried over one big question: If nuclear war broke out, yet the base remained standing, would she share her food with our unprepared neighbor and her two sons? Or would she apologize, then close and lock our door?

It’s hard to imagine, now, the omnipresent dread shadowing those years before the U.S. and the Soviet Union signed treaties limiting missile development and deployment. If I tell you that when I was 11, I was required to take a six-week long class called “Civil Defense,” intended to teach us how to survive a nuclear strike, you might think that gruesome or even cruel. But my classmates and I, then stationed at Homestead, Florida, listened to our fathers’ planes taking off and landing every day around the clock. And that Civil Defense class gave me private answers to my some of my impossible-to-ask questions.

Our teacher handed out a one-inch thick workbook, full of maps and math problems. I studied the expected damage and fatality at various distances from the blast site. Some people would die in the fireball or the shock wave, some later from burns or catastrophic radiation exposure. Everyone within thirty miles would die or be seriously injured.

I learned about radiation poisoning: vomiting at the lowest level of exposure; bleeding from the mouth, skin, and kidneys at the next level; delirium, coma, then death. I learned how to triage who might survive and who definitely wouldn’t. My own exposure to fallout would depend on distance and wind conditions. Using the workbook’s math problems, I calculated how soon I’d have to find a shelter before exposure killed me, and then how long I’d have to stay there as radiation levels declined. It looked, to me, hopeless. Even if I survived a direct strike, normal winds could spread enough radioactive fallout fast enough that people hundreds of miles away could die after only an hour’s exposure. Our neighbor in Kansas City, I realized, had been right.

More than 50 years after the Missile Crisis, I cannot sleep without the sound of engines nearby. I keep a turbo fan right beside my pillow, and if I’m away from home an app on my phone plays engine noise for me. If I wake in the night, and all is silent, the thought still flares through my mind: Something is wrong.

Send A Letter To the Editors