The cast of La La Land perform “Another Day of Sun.” Courtesy of Lionsgate.

“Without a nickel to my name/ Hopped a bus/ Here I came …” So sings a young woman at the start of La La Land, the original musical film by Damien Chazelle and this year’s leading Oscar contender. The number begins with a pan across mostly solitary individuals sitting in a traffic jam on an L.A. freeway. As we move past open car windows, we hear that each driver is listening to something different. Suddenly, one female driver begins to sing and steps out of her car. Dozens of others join her, as a spectacular song and dance number—“Another Day of Sun”—materializes amidst cars for as far as the eye can see.

The opening is a perfect example of the “bursting into song” for which the musical genre is known (and occasionally maligned). Without cause or provocation, characters break out of their ordinary lives and into a heightened state wherein they express feelings of love and longing, happiness and despair. Except for the anti-sentimentalists among us, the musical lifts us out of our humdrum reality, if only for a moment.

Surprisingly, this tendency in musicals stems not from a desire to escape but rather the need to address what is lacking in our lives. This was a central concern of musical films made by Jews, Mexicans, and African Americans in the early days of sound cinema. Ministering to audiences who were dealing with the pains and anxieties of migration, ethnic musicals offered stories about people who burst into song as a way of establishing connections to one another and to their homeland.

In the late 1920s, Hollywood filmmakers routinely built an explanation of the use of song and dance into their films. Stories typically revolved around show business and took place in performance contexts, including the rare Hollywood film that acknowledged the experience of migration, The Jazz Singer (1927). The only time people burst into song without justification was in films about people of color, who were portrayed as naturally prone to singing and dancing (see Hallelujah!, 1929). Ethnic musicals operated within a different logic, one that assumed a cultural affinity with its audience. In these films, made outside of the Hollywood mainstream, ordinary people sing and dance as a matter of course, no special context required. Their characters perform with their audience, rather than for it.

As many already have noted, La La Land does indeed nod to the Hollywood musicals of old, such as An American in Paris (1951) and Singin’ in the Rain (1952) and the French quotations of those films, such as Jacques Demy’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). But the film’s emphasis on migrant characters in search of love, community, and belonging places La La Land squarely within the ethnic traditions that are foundational to the genre.

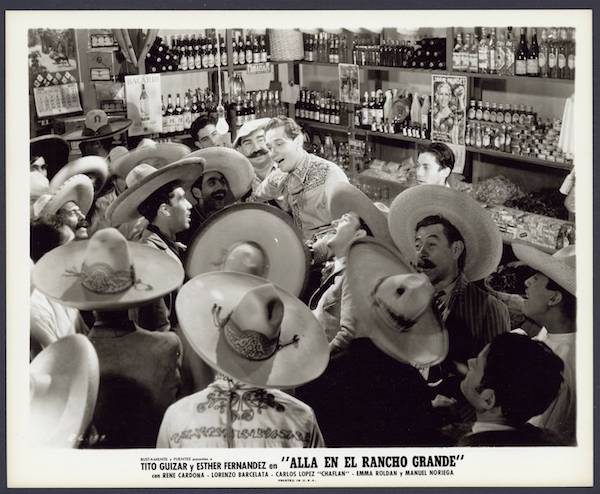

Characters sing together in Allá en el Rancho Grande (Over on the Big Ranch, 1936).

Take, for example, Allá en el Rancho Grande (Over on the Big Ranch, 1936), the most popular Mexican film of its time. While Hollywood offered a cycle of films about chorus girls and stage door Johnnies (see 42nd Street, 1933; Gold Diggers of 1935; Stage Struck, 1936), director Fernando de Fuentes presented a simple story about Mexican ranch life with folk songs and dances. He quickly found that the film’s biggest audience was among Mexican immigrants living in the United States—they constituted a critical mass that hundreds of movie theatres, large and small, served in cities across the country.

In Los Angeles, the film attracted English-speaking audiences, too, yet elicited back-handed compliments from reviewers in the mainstream press. Variety applauded its efforts, but ultimately declared that it was “not a musical in any sense of the word,” objecting to the “casual way” in which songs and dances entered and exited the story without explanation. So unfamiliar was the reviewer with this approach that he dismissed the film as a rudimentary attempt at the musical. He ended his review by condescending to de Fuentes, advising him to look to Hollywood for “a more thorough lesson.”

Other ethnic musicals similarly departed from the status quo. Clarence Brooks and Harry Gant’s black-cast film, Georgia Rose (1930), surprised audiences and critics by rejecting the stereotypical imagery of “the Negro singing spirituals, eating watermelon and shooting craps,” as one reviewer noted. Instead, Brooks and Gant told a story about a modern black family who leave the South in search of opportunity up North. And as an answer to the assimilationist message of Hollywood’s The Jazz Singer (1927), Joseph Seiden released Mayne Yiddishe Mame (My Jewish Mother, 1930), the first Yiddish sound film. Made for an audience of Jewish immigrants, Mayne Yiddishe Mame demonstrated that while American success was alluring, nothing replaces the sanctity of the family.

In these films, as with Rancho Grande, ethnic filmmakers revealed a new purpose of the genre: to serve the needs and desires of a people for whom migration is a reality. With the coming of the U.S. entry into World War II and the ensuing separation of families, the Hollywood studios realized that changing times necessitated a shift in the musical as well. As MGM producer Arthur Freed recounted in an interview, “Gone were the gigantic production numbers, the trick camera angles, the dances and songs that stopped the plot cold until the last chorine waved her last ostrich feather in the camera’s focus.”

Instead, stories about small-town communities and the endurance of home dominated the genre, epitomized by Meet Me in St. Louis (1944). In Vincente Minnelli’s musical, the lives of the Smith family of St. Louis are disrupted by the prospect of migrating to New York City at the turn of the century. This film resonated deeply with World War II-era audiences and its theme of social unity in the face of change shaped later classics, including The Music Man (1962) and The Sound of Music (1965).

La La Land begins by introducing characters who have already ruptured their lives by leaving home and are striving to make it in a new place. As the opening number shows, these young hopefuls are as diverse as the city in which they live and they are seeking careers in L.A.’s many creative industries. Mia, the main character played by Emma Stone, embodies their journey. She left Boulder City, Nevada in order to become an actress. But making it is an uphill battle, she soon realizes. At her lowest point, she tells her boyfriend Seb (Ryan Gosling), a jazz pianist, “I’m going home.” When he insists that she is home, she responds, “Not anymore.” As these moments suggest, L.A. is full of migrants who enter and exit the city. But these migrations come at a significant cost to the maintenance of relationships, which Mia and Seb soon understand.

As “Another Day of Sun” reveals, the musical allows characters to shift from a state of isolation to one of inclusion. It creates a sense of belonging for both its characters and its audience in the process. Ethnic musicals did this as a matter of course. Often, audiences sang along to songs they already knew—these early musicals typically included a mix of familiar songs and original numbers—effectively transforming the movie theatre into a musical community of its own.

This tradition extended to the Hollywood musical in films like Meet Me in St. Louis, in which the use of folk songs, “Skip to My Lou” and “Meet Me in St. Louis,” fostered a connection between the Smith family and its 1940s audience. Even today, the annual The Sound of Music sing-along at the Hollywood Bowl brings together audiences from all walks of life. They happily sing “Do Re Mi” and “My Favorite Things,” songs that have over the years become part of an American folk heritage. La La Land, like the musicals that precede it, brings people together again and again, from the opening song, to Mia and her roommates in “Someone in the Crowd,” to the impromptu reprise of “City of Stars,” casually sung by Mia and Seb at the piano.

To understand La La Land’s appeal, we might well look to the genre’s long history of speaking to people on the move. The struggle between pursuing dreams and sustaining relationships, leaving home and staying put, is a recurring theme. Delving into the musical’s origins, we find that this was of particular concern to migrant communities. Just like Mia, musical film audiences are searching for a better life.

Send A Letter To the Editors