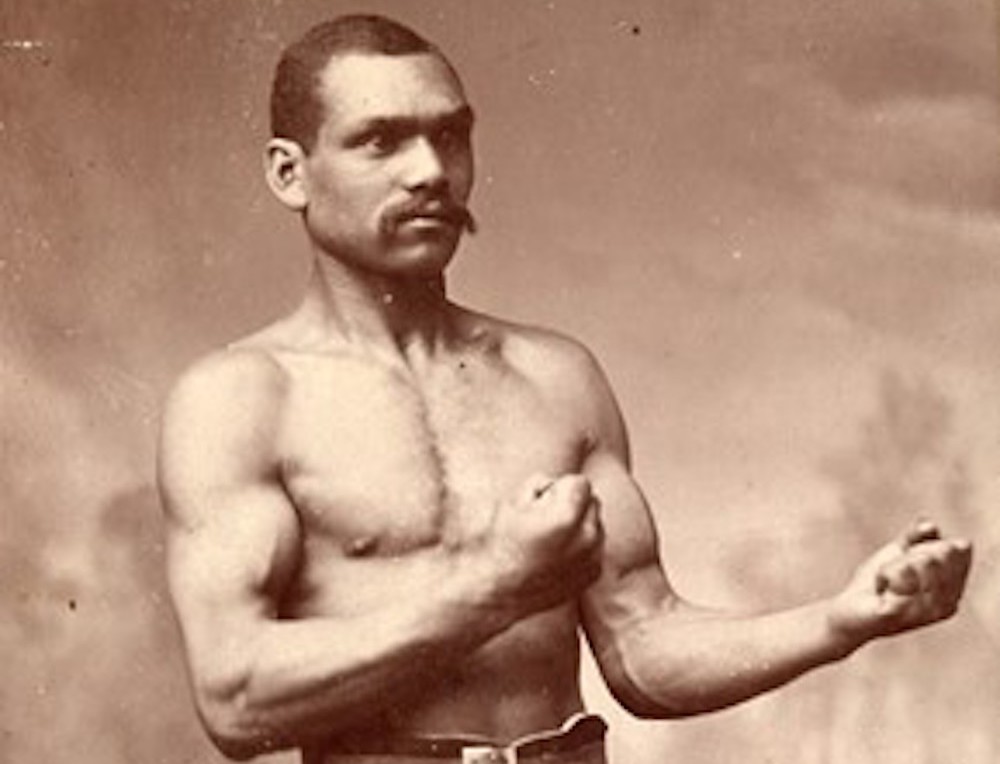

George Godfrey, the “Colored Heavyweight Champion” from 1883 to 1888. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

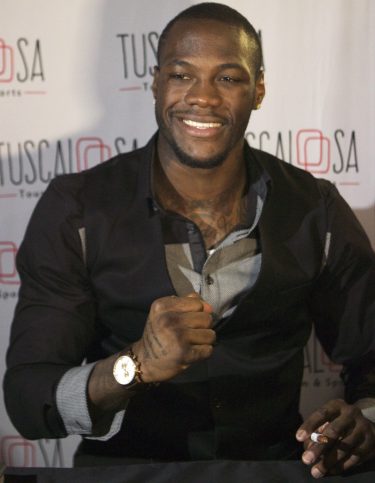

Standing 6 feet 7 inches, with an athlete’s body, Deontay Wilder dreamed of going pro in either football or basketball. But at 19, with a newborn girl who had spina bifida and medical bills piling up, he knew he had to step up. His jobs busing tables at Red Lobster and IHOP and his shift driving a beer truck just weren’t going to cut it.

As a young man in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, without a college degree, he didn’t have much of a choice. So he did what countless black men have done for more than a century to support their families: He turned to prizefighting. As Wilder said of his daughter during his Olympic debut in 2008, “I want to make sure she’s financially stable. I want to make sure she doesn’t have to struggle. I want to make sure I can support her through college.” In other words, Wilder told the world that he was a man, joining a long line of fighters who have taken the same stance as a way of defining themselves in the perilous world outside the ring.

For more than a century, black prizefighters have fought to shift the public narrative on their sport towards a patriarchal view of manhood. While most conversations about a boxer’s worth revolve around wins and losses and aggression in the ring, black boxers have expressed their ideals by intertwining their physicality, financial success, and the ability to take care of their families.

The first black fighter to publicly connect his success boxing with supporting his family was George Godfrey, Colored Heavyweight Champion from 1883 to 1888. When the press interviewed him, Godfrey rarely missed a moment to highlight his patriarchy. As Godfrey told the San Francisco Chronicle in 1888, “I’ve got a wife and six children, and I follow fighting as people follow any other calling.” In an interview three years later, he said, “I have a family to look out for and I must get something for them to live on should any accident take me from them.” He told a reporter that an upcoming $5,000 fight would help him support his kids’ college education.

Historian Kevin Gaines suggests that at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, “elite blacks celebrated the home and patriarchal family as institutions that symbolized the freedom, power, and security they aspired to.” According to Gaines, “African Americans laid claim to the respectability and stability withheld by the state and by minstrelsy’s slanders.” Celebration of the black family, then, represented victory over the worst effects of slavery, Jim Crow, and structural racism. Being a black man in America has often meant proving oneself to a society that has tried to deny one’s manhood, and the legacy of prizefighters shows how this worked.

At a time when the popular press dehumanized black citizens and mocked black fighters as childlike Sambos, Godfrey’s public persona countered those depictions. In the 1880s, newspapers filled their pages with advertisements for black-face minstrel shows, cartoons depicting black people as Sambo caricatures, and articles mocking black Americans. This racism flooded the sports section, too. White writers commonly referred to black fighters as “darkey,” “coon,” “sambo,” and “nigger.” They called Godfrey “Old Chocolate.”

White fighters didn’t treat their black counterparts any better. Heavyweight champion John L. Sullivan told Godfrey, “George, when I get ready to fight rats, dogs, pigs and niggers, I’ll give you the first chance.”

Godfrey understood these attempts to treat him as less than a man. Inside the ring, he tried to take his anger out on his opponents—he bragged he liked to fight white fighters because they were easier to beat.

Outside the ring, he paraded his patriarchy for the public to see. He talked about spending time with his family, and whenever Godfrey could avoid the hyper-masculine world of the boxing gym, he did. He owned his own gymnasium in Boston, where he taught lessons to a mainly white clientele looking to build their bodies, but he also had his house outfitted with sparring and exercise equipment, so he could train with his family. As one paper noted, “Godfrey would rather train at his home than elsewhere, for he is more contented and does not have to worry about his family.” He defined being a man not just as being a top fighter; he saw himself as a man because he took care of his family.

Godfrey was not alone. Hank Griffin, one of the top black heavyweights in the early 1900s, regularly brought his wife and kids with him while training, and could be spotted in Los Angeles rowing a boat with his family as he conditioned for upcoming fights. Heavyweight Joe Jeannette brought his wife and kids with him when he fought overseas, and could be seen touring museums with them. After he retired he bought a piece of land in New Jersey and built a gas station and a boxing gym so he could keep his family close.

In 1938, the greatest fighter of them all, Joe Louis, authored an essay titled, “Why Married Men Become Champions,” where he extolled the virtues of family life. In fact, very few fighters failed to perform a public persona of the manly patriarch.

Of course, there are exceptions. Floyd “Money” Mayweather, the most famous fighter today, who has earned nearly a half billion dollars in the ring, plays up his misogyny instead. The flashy clothes, cars, and jewelry we often see fighters wearing are another way to publicly display manhood—aimed as a show of bravado towards other men.

The bling of financial success, however, is not insurance against society’s judgments. In fact, it only invites closer inspection—particularly when a fighter goes broke. Many great black fighters have become penniless, including George Dixon, Joe Walcott, Sam Langford, Joe Louis, Ezzard Charles, Jimmy Bivins, Beau Jack, Aaron Pryor, and Rocky Lockridge. Many were meal ticket men, who fought in low-paying fights, but their financial losses were celebrated as much as if they had lost in the ring.

100 years ago, one white writer observed, “It seems to be an unfortunate trait with the colored fighters that they have not sense enough to lay up a little of worldly goods against the coming of old age. Practically every one of them has been an object of charity at some time or other. Contrast these negro boxers with the average white scrapper of the same skill and prominence. While the colored man grovels in poverty the white chap toils in the lap of luxury.” This feeling that the press will soon remind him that he lacks the manly discipline required to succeed looms over the black fighter, waiting to count him out. Embracing the role of the patriarch is one way to fight back against that narrative.

Deontay Wilder, WBC heavyweight title holder. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

130 years after Godfrey’s reign, Deontay Wilder, the heavyweight champion of the world, has positioned himself as so many before him have. Since 2008, he has consistently linked his manhood to his desire to support his family. In a 2017 interview, he noted “I keep boxing for my children, for all of them. I’m building a legacy for my children. I’m making wealthbread for them. Not only what they eat but for their families, too … their kids and their kids’ kids. There’s going to be a long history line of Wilders eating.” Like Godfrey, Wilder trains with his kids around the gym. They are with him stretching, watching him spar, and they join him on fight night, too.

Wilder presents himself as a father—the ultimate dad—to an American society that routinely, and publicly, depicts black men as deadbeat dads. In 1998, Sports Illustrated infamously placed a young black boy on their cover holding a basketball, with the caption “Where’s Daddy?” The accompanying story was an expose of athletes, mainly black men, and their inability to consistently be in their kids’ lives. Sports Illustrated, like other media outlets, traded on a tired trope. Wilder knows this. In fact, every black man knows this.

In his latest fight, on March 3, 2018, Wilder faced Afro-Cuban Luis “King Kong” Ortiz, another gladiator heavyweight with a daughter who has special needs. At the end of the fight, a 10th-round knockout win by Wilder, a beautiful thing happened. After slugging each other across nearly 30 minutes, the two battlers hugged each other, acknowledging the sacrifice both men made for their families. A few minutes later, in his post-fight interview, Wilder told the world the fight represented “two fathers fighting in the ring for their daughters.”

When Wilder keeps his family in the public eye as he did at the end of that fight, he is saying “I am a man” on terms other than those offered by the world. And as long as society keeps denying black men an unabridged path to manhood, black men will turn to boxing to announce it.

Send A Letter To the Editors