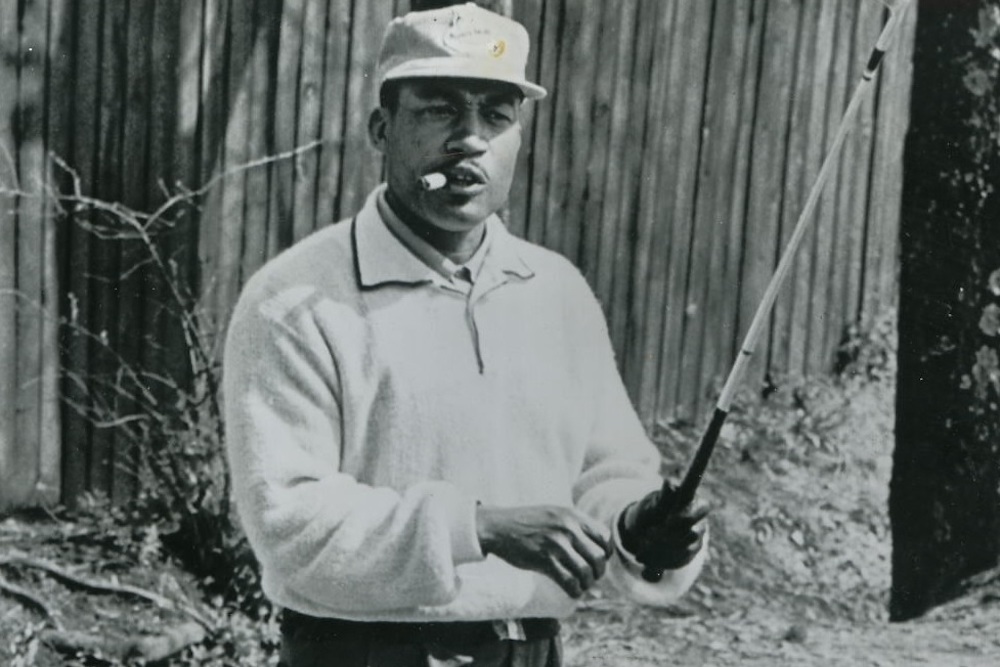

A crucial figure in the history of golf and the United Golfers Association, Charlie Sifford was known for his cigar-chomping style. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In 1951, as a renewed civil rights movement dawned in America, African-Americans from around the country gathered in Atlanta for the annual convention of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). There they heard from important black leaders of the period, including Thurgood Marshall, Roy Wilkins, Mary McLeod Bethune, and Benjamin Mays.

In 1951, as a renewed civil rights movement dawned in America, African-Americans from around the country gathered in Atlanta for the annual convention of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). There they heard from important black leaders of the period, including Thurgood Marshall, Roy Wilkins, Mary McLeod Bethune, and Benjamin Mays.

But then some of the delegates did something curious. They boarded busses, headed to the New Lincoln Country Club, Atlanta’s black golf course, and watched the end of a golf tournament organized by the United Golfers Association (UGA). That day’s winner—a then little-known player named Charlie Sifford—enjoyed his first victory in a professional golf tournament, 10 years before he’d go on to become the first African-American to join the PGA tour.

Long overlooked by sport fans and historians alike, for over 50 years the UGA organized a national golf tour that was open to all players regardless of their race. Beginning in 1926, the organization was both the primary outlet for elite, black professional golfers and the provider of access to competitive golf for thousands of everyday African-Americans.

Forged by pioneering black golf clubs in the Northeast, including New Jersey’s Shady Rest Country Club, the UGA quickly became a national entity, organizing events nationwide by the 1930s. The competitors on the tour pioneered professional golf in America, helping organize local clubs in their cities and fighting segregation at municipal courses.

John Shippen, one of America’s first professional golfers, in 1899. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

One of its heralded players, John Shippen, was also one of America’s first professional golfers of any race. Shippen competed in several U.S. Opens before the United States Golf Association (USGA) prevented African-Americans from participating after 1913; he even tied for fifth place at the 1896 U.S. Open, the second ever held. Another top early player was Robert “Pat” Ball, who successfully protested discrimination in Chicago’s city golf championship in 1918. Ball won the Cook County Open three times, staged exhibition matches against white pros in the Professional Golfers’ Association of America (PGA), and prevailed in a lawsuit against the USGA after it barred him from the 1928 Public Links Championship.

Following World War II, a new generation of players emerged from the UGA to once again break down the color line and desegregate PGA and USGA events. These players included Sifford, Ted Rhodes (who reintegrated the U.S. Open in 1948), and Lee Elder (who integrated the Masters Tournament in 1975). Sometimes the tour challenged discrimination in the PGA and USGA by organizing UGA tournaments on golf courses that had previously hosted PGA players, helping black players match their talents with top white pros simply by posting comparable tournament scores. When Ted Rhodes won the UGA’s 1948 Houston Open on Memorial Park Golf Course, fans noted that his score flirted with acclaimed white pro Jimmy Demaret’s course record.

The UGA drew talented men but also had a notable feature that distinguished it from other black sporting organizations: a full women’s division. Over the years, female competitors like Ann Gregory, who, in 1956, became the first black woman to play in a USGA national championship, and Althea Gibson, who desegregated the Ladies Professional Golf Association (LPGA) tour in 1963, encouraged more black women to take up the game.

UGA events also attracted support from prominent black celebrities, entertainers, and politicians. Joe Louis, the heavyweight boxing champion from 1937-1949, was the world’s most popular athlete and provided key support to the tour and its players. Other advocates included Oscar De Priest, the first African-American elected to Congress from outside the South, boxers Harry Wills and Sugar Ray Robinson, football star Kenny Washington, baseball pioneer Jackie Robinson, and entertainer Sammy Davis Jr. Over the years, the list of white people who supported UGA events was equally impressive, from entertainers such as Al Jolson, Johnny Weissmuller, Frank Capra, and Bing Crosby, to politicians such as Governors Len Small (Illinois) and G. Mennen Williams (Michigan), and Mayors Albert Cobo (Detroit), Edward Joseph Kelly (Chicago), and Thomas A. Burke (Cleveland).

Corporate sponsorship and the attendance of such prominent fans helped expand UGA tournaments into larger, multiday events that celebrated more than just the game of golf. Banquets, dances, and speeches sometimes accompanied the tournaments, drawing substantial crowds and media coverage. The 1936 UGA national championship, held at Philadelphia’s Cobbs Creek Golf Course, drew so many observers that the city’s mounted police were called in to hold the gallery back. White fans flocked to tournaments too, especially when celebrities like Joe Louis and Sammy Davis Jr. were on hand; one quarter of the gallery was white at the 1941 UGA national championship, held at Boston’s Ponkapoag Golf Course.

The UGA turned the standard geography of segregation on its head. Players like Sifford and Rhodes faced blatant abuse in the 1950s when they attempted to desegregate PGA tournaments outside the South, especially in California and Arizona. Meanwhile, previously all-white courses in Southern locales like Dallas, Memphis, and Louisville welcomed them warmly for UGA events.

There was even a period when white tournaments were not necessarily the most attractive option for black golfers. In 1949, Rhodes received an invitation to the PGA’s $5,000 Cedar Rapids Open in Iowa, scheduled for the same weekend as the UGA’s $4,000 Joe Louis Open in Detroit. Louis himself encouraged Rhodes to play the white event that week, yet Rhodes turned down the PGA and instead showed up in Detroit—and promptly won Louis’ tournament. Black players appreciated the social significance of accessing white tournaments, but they were also professionals. They sought the events they believed gave them the greatest chance at winning the most money.

Meanwhile, as baseball integration effectively decimated the Negro Leagues, some of the most important black golf tournaments were organized after the PGA and USGA started welcoming black participants. The Southeastern Golf Tournament, nicknamed “The Classic,” which ran from 1964 until the early 1980s on Georgia’s Jekyll Island, drew top black golfers and featured musical performances from Otis Redding, Jerry Butler, Wilson Pickett, and Percy Sledge.

The UGA also remained committed to its vision of a truly race-blind golf tour. Unlike the Negro Leagues, which did not experiment with the occasional white baseball player until the 1950s (and then only in the face of rapid decline after Robinson’s integration of Major League Baseball in 1947), the UGA was never an “all-black” golf tour, and its events were always open to everyone. Over the years, several white players competed in, and even won, its tournaments. Another notable UGA gesture to integration was its name—United Golfers Association—which did not include “colored” or “negro” but instead invoked the race-blind notion of “united.” Its founders chose to adopt such a stance from the beginning, at a time when many black organizations, including the NAACP, specifically invoked race in their titles.

The UGA was also different in the way its golfers actually played the game. Competitors like Howard Wheeler introduced a new aesthetic to professional golf—styles, practices, words, and gamesmanship that fans had not yet seen in the world of white competitive golf. This new look included Wheeler’s cross-handed grip and trick-shot performances, Ted Rhodes’ colorful wardrobe, and Charlie Sifford’s iconic cigar chomping.

As the UGA helped elite black players compete against leading white professionals, a curious sentiment emerged in the early 1940s: a notion that professional golf was actually more racially tolerant than other sports, not less. Indeed, black golfers competed against the world’s best white players—including Southerners like Byron Nelson, Ben Hogan, Sam Snead, and Babe Didrikson Zaharias—at least five years before a lone Jackie Robinson stepped onto a Major League Baseball field. And fans noticed, some finding in golf the motivation to challenge baseball segregation.

“Negro stars are competing … in golf tournaments,” hailed one black newspaper in 1939. “Baseball seems to be the most stubborn of all, but, it too, can be cracked, and it will be.” Another newspaper told readers that golf was “open to all.” This burst of optimism was short lived, of course: The end of World War II presented fans with a new set of high-profile examples of the PGA and USGA backing discrimination over integration, especially in the all-important events hosted by private golf courses, such as the Masters at Georgia’s Augusta National Golf Club.

While the UGA provided some black players national recognition, by the 1950s their success also exposed the tour’s limitations. The discrepancy between white and black professional golf was often greater than in other sports, especially in terms of the facilities. Charlie Sifford and his fellow competitors honed their skills on the nation’s public links, including popular municipal courses in poor shape. Trying to break into PGA tournaments at generally nicer courses meant tackling more than just racial discrimination; it also meant altering one’s game dramatically for faster greens, well-watered fairways, and different sand textures. Sifford and others who later managed to crossover to the PGA fondly remembered the UGA but always bemoaned the “lousy” course conditions they had to contend with.

UGA success also failed to pay the bills. Even the tour’s best players struggled to make ends meet and relied on outside jobs, informal gambling, and support from patrons. Famed singer Billy Eckstine once hired Sifford to be his valet in order to support the golfer, while fans in Los Angeles established a trust fund to aid the play of UGA pros and help them gain admission to white tournaments.

Despite these challenges, the UGA sustained a lasting, national reach that rivaled any single black baseball league. It featured a steady stream of players from all regions and hosted tournaments in Los Angeles to Boston and everywhere in between—including Chicago, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Indianapolis, Philadelphia, Washington, Dallas, Kansas City, Memphis, and Miami. The tour and its fans confronted issues of diversity, economic mobility, and class dynamics within the black community like no other sporting association had to: Its players ranged from poor former caddies from the South to middle- and upper-class professionals who held memberships at elite country clubs.

And as the country’s only national golf tour for black players, the UGA featured nearly every African-American who competed on the PGA and LPGA tours before the 1996 professional debut of Tiger Woods—27 men and three women. Few other American sporting organizations can claim such a distinguished history.

Send A Letter To the Editors