Rigaberto Moreno picks and cleans crimson grapes in Laton in California’s San Joaquin Valley, October 2002. Courtesy of Gary Kazanjian/Associated Press.

California’s San Joaquin Valley is often dismissed as small and rural. To the contrary, it’s a massive area of farms, ranches, small towns, and growing cities, emblematic of the American West as a blend of Old West values and New West technology. It’s also historically distinctive as one of the most ethnically diverse regions in the United States.

Most Americans know little, and think less, about this complicated and neglected region. Novelist Manuel Muñoz describes the valley, where he was born and grew up, as “a strangely unexplored area of our nation. As a region, it gives so much of its bounty to the rest of the country and receives little in return.” By bounty, he means food. He could also mean the bounteous way valley migrants and immigrants have nurtured our collective American story.

The agriculture of the valley today is a joint creation of 19th century Mexicans, Californios, and Chinese, as well as 20th-century African-Americans, Sikhs, and Okies—along with dozens of other ethnic groups, like Assyrians, Croatians, Volga Germans, Russian Molokans, Mien, Hmong, and my own family of Basques and Béarnais. Farming was the lure for many migrants, who often found themselves in a triangular squeeze of resentment, rejection, and accommodation. While some who came to exploit the land then found themselves exploited, many immigrants bettered their lives.

By the 1890s, settlers from Japan, Sweden, Italy, Norway, Portugal, Turkish Armenia, and other regions helped make the center of the San Joaquin Valley “one of the more cosmopolitan regions in the country,” says the scholar David Vaught. By 1900, farming colonies blurred into new settlements, “creating a vast, unbroken region of small farmers.”

That’s when my Béarnais-American grandfather grew wheat and barley as a tenant farmer along the San Joaquin River. After World War I, with the expansion of irrigation and the development of deep-well turbine pumps, he moved to the interior valley to plant a vineyard and cotton on his own forty acres. One-third of the nation then lived on farms and ranches. Today, after a stunning hundred-year shift, a scant one percent of Americans remain on the rural lands that feed us.

Nicknamed “The Other California” because its character is distinct from the state’s tourist and metropolitan haunts, the San Joaquin Valley joins the Sacramento Valley to stretch 450 miles through nearly three-fifths the length of the state. It comprises the largest area of the richest soil in the world. Most farmers don’t like the generic term Central Valley because it expunges the distinctiveness of the two valleys that grow more than 230 crops and one-third of the nation’s fruits and vegetables. This expanse is also more populated than Oregon and larger than Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Massachusetts combined.

A bit of agricultural and environmental history is important here. At the heart of the Great Depression, during California’s worst recorded drought, farms were going under as their wells pumped dry. Unless something was done, it was predicted that the area’s underground aquifer wouldn’t last another thirty or forty years. So the federal government launched the Central Valley Project, joined later by the California State Water Project, building dams, reservoirs, aqueducts, canals, tunnels, and lateral ditches to send water up and down the state. An irony of the water projects is that they killed off half the smaller family farms in the valley, while helping bigger and richer corporate “farmers” like Standard Oil, Prudential Financial, Southern Pacific Transportation Company, Getty Oil, and Shell. “Get big or get out” became the valley apothegm. My family got out.

In his novel Census, Jesse Ball writes:

No one but farmers understands fairness.

What is there to understand? I asked.

That there isn’t any.

A story that doesn’t often get told is how many valley farmers and ranchers, like most of my neighbors of immigrant and migrant stock, hung on. California farms remain smaller on average than in the rest of the nation. A current aerial flyover map of Madera County in the center of the state, the area where I grew up, shows hundreds of small parcels of twenty acres or less. Of 1,507 farms and ranches in the county, most are small: half are less than 60 acres and 1,095 are smaller than 180 acres. Only 118 are 1,000 acres or more. Some small farms get rented to larger ones. The original 40 acres once owned by my grandfather are now leased for table grapes to the biggest agribusiness investors in the San Joaquin Valley.

The problem of vanishing water—a defining characteristic of both the urban and rural West—is still extreme in the San Joaquin Valley. All farmers and ranchers, large and small, and the workers on the land suffered during this decade’s seven-year drought. With no federal or state surface water, farmers let millions of acres go unplanted, costing agriculture billions of dollars. Hot, dry winds stirred up fungus spores from the dirt, causing a silent epidemic of deadly valley fever, mostly among the poor. A front-page photo in the Fresno Bee in 2015 showed Cha Lee Xiong on his small twenty-acre farm near Sanger, hunkered down in a barren field with dirt in his cupped hands after his well went dry.

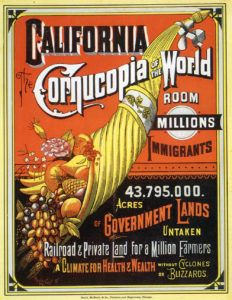

Advertisements like these recruited farm workers from around the world to California’s San Joaquin Valley. Courtesy of Frank Bergon.

In 2016, as the drought neared its end in other parts of California—but not in the valley—a controversial and sullied presidential election revealed a widening gulf between the country and the city. I came to see this split while writing about the valley, where mostly conservative small-town and rural residents sensed a clamor for their votes without a matching desire for understanding or empathy.

My initial intention was merely to write profiles of valley people I knew. Eventually my portraits became a book about generations of immigrants, migrants, and their descendants, who remain suffused with a prevailing ethic from the 19th century. An Old West state of mind emblazoned the career of the Dust Bowl migrant Darrell Winfield, who for thirty years reigned as the iconic Marlboro Man without abandoning his trade as a working cowboy. My valley friend Fred Franzia, the legendary creator of the best-selling wine in history, popularly known as Two-Buck Chuck, consciously adopted the work ethic of his Italian grandmother who’d immigrated to the arid valley of rattlesnakes and jackrabbits.

In the new millennium, the San Joaquin Valley endures as one of the most racially and ethnically rich areas in the country. Two out of three people are racial or ethnic minorities, and two out of five minorities are foreign-born. Belief in the valley as a place of individual freedom and economic opportunity for those who pursue education and work hard—a faith American at its core, though Western in its intensity—has become harder to maintain beyond a wistful dream in an era of gated communities and suburban isolation.

Not all is bleak. Sal Arriola, a Mexican immigrant who crossed the border with his family without authorization when he was three, now farms the biggest vineyards in the country for the family-owned Bronco Wine Company. Irene Waltz, of mixed German and Chukchansi heritage, told me she experienced no discrimination in valley schools, worked for nearly forty years as the manager of grape contracts for Constellation Brands, and served as treasurer and now insurance executive for the Picayune Rancheria of Chukchansi Indians. Albert Wilburn, a valley high school valedictorian and student body president who became the first black captain of the Stanford football team, and a physician, remembers his boyhood valley as a place of tolerance.

“We assumed tolerance,” he told me. “It came to us through osmosis and was as natural as drinking water and breathing air.”

From many rural and small-town people I heard how the valley gets a bum rap. Or no rap at all. A common refrain arose: “It’s like we don’t exist. We’re invisible.” If we are to understand America as it really is, the San Joaquin Valley and all its people must become visible.

Send A Letter To the Editors