Medical sociologist Grace Yoo. Image courtesy of Pamela Palma.

How have immigrant communities addressed a rampant disease—and maybe beaten cancer?

Some answers to that question lie in the story of a San Francisco campaign against hepatitis B.

Americans of Asian heritage have by far the highest rates of chronic hepatitis B virus infection; while less than 1% of the total U.S. population has “hep B,” one in ten Asian Americans are infected. And San Francisco, with a large population of residents of Asian heritage, has the highest rate of liver cancer in the country, reflecting in part high levels of undetected chronic hepatitis B infection.

More than a decade ago, activists and community members in San Francisco launched a major media campaign that portrayed people of Asian heritage as heroes for getting tested, screened, and vaccinated. It was the very first time that I had seen Asian Americans who looked like me in a mainstream ad.

By engaging Asian Americans as messengers to the community, including hard-to-reach immigrants, to change perceptions of the infection, the campaign offers broader lessons for how to address other hard-to-discuss public health issues.

The campaign started in 2007, with AsianWeek Foundation organizing diverse Asian Americans and immigrants to focus on ending hep B disease. Ted Fang, then AsianWeek’s executive director, brought together health leaders, including Samuel So, MD, of the Asian Liver Center at Stanford University, and Janet Zola (then with the San Francisco City and County Department of Public Health), to form a coalition called San Francisco Hep B Free (SFHBF). Mitch Katz at the San Francisco Department of Public Health put his full support behind the effort.

This coalition also included immigrants and leaders in Asian American organizations, as well as in the media, government, community, and business sectors. The campaign’s goals were to move Asian Americans to get screened and to convince public and health care providers to test and vaccinate Asian Americans for hep B.

This coalition set out to develop communication strategies that would break the silence about hepatitis B and normalize discussion of it. Without funds to start, organizers began by soliciting strong public statements of support from then-Mayor Gavin Newsom, who proclaimed the goal of making San Francisco free of hepatitis B.

San Francisco Supervisor Fiona Ma, then the only Asian American on the board of supervisors, wrote and led the passage of legislation calling for testing and vaccinating all Asian Americans in San Francisco, and also talked publicly for the first time about her own chronic HBV infection.

Having broken the ice through effective communication, the coalition soon got funding for bus signs and billboards introducing the campaign. In 2007, bus ads featuring Newsom encouraged testing for hepatitis B.

In 2008, an ad campaign called “B a Hero” featured Asian Americans with drawings of capes and Superman costumes superimposed on their everyday clothing, with a “B” appearing in place of the Superman “S.” The concept: getting tested for HBV and talking to friends and family about being tested would make anyone a hero. This upbeat approach, designed by a team of Asian Americans, proved very effective.

Courtesy of Grace Yoo.

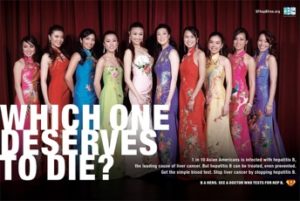

The 2010 ad strategy was tougher because it focused, in a very personal way, on the statistical likelihood of developing cancer by having an undetected infection. Featuring local volunteers of various Asian ethnicities and backgrounds as beauty pageant contestants, one ad noted that one in 10 Asian Americans were infected with hep B, the leading cause of liver cancer, and posed the question, “Which One Deserves to Die?” A second ad asked the same question over a tableau of an inter-generational Asian family gathering for a photo.

Courtesy of Grace Yoo.

As a medical sociologist, I researched the roles of Asian Americans, their leaders, and celebrities in this San Francisco effort—the first study of such health promotion campaigns. I was particularly interested in how “narrative communication”—official stories, invented stories, and personal stories—can educate the public about a particular health issue. Such narratives had shown results in the Witness Project, a program in which local African-American breast and cervical cancer survivors talk about, or “witness,” their cancer experiences.

What I learned from San Francisco’s campaign was that breaking the silence and using personal narratives from respected Asian-American leaders helped destigmatize hep B. While the disease had previously been associated with “bad people” or “bad behavior,” the campaign repositioned it as something that the community could act to confront, in the service of greater health for all. In many Asian countries where hep B is common, infected patients are acculturated to feel ashamed or fearful, and consequently hide their disease. A common perception in Asia is that those infected somehow deserve it.

The San Francisco campaign successfully reframed this discourse among Asian immigrants and Asian Americans by providing factual information on transmission, emphasizing medical solutions, and creating positive emotions and feelings of empowerment. In effect, as then-San Francisco Board of Supervisors President David Chiu told me in an interview for my study, what the study did was to bring hep B “out of the closet.”

Destigmatization is a first step, but it is also a process that needs to be continually reiterated. Jason Liu, an activist who was a premedical student at the time, told me that even when he told Asian Americans that their primary mode of hepatitis B infection was from fluids transferred during the birthing process, the stigma is still difficult to eradicate given that hepatitis B can be transmitted sexually or through drug use.

One of the most important strategies to counter the persistent stigma was to have well-known and respected Asian Americans speaking out. Personal disclosures by Supervisor Ma and Alan Wang, then a news anchor at the local ABC affiliate, were particularly helpful. In an on-air piece, Wang, who said he was inspired by Ma’s disclosure, described the discovery of his own infection status and his ongoing monitoring and treatment to prevent liver cancer. He has proven to be a key resource and voice for the campaign by talking about his hepatitis B infection openly.

Jeanette Tam, who worked for a health plan focused on Chinese Americans at the time, told me that the campaign had broken a barrier. “This is not something that Chinese people and Chinese families discuss: weaknesses. And so with Fiona Ma coming out and talking about that, it was an eye opener to me.” That a public figure would risk her public image by coming forward impressed Tam enough to encourage her to speak up as well. Tam said, “And even if you choose to tell someone to get prevention, get tested, and get vaccinated, that’s good. And if it goes as far as, ‘You know what? I’m going through it too,’ it puts a human face on it so that people don’t have to feel secretive.”

Focusing on the upbeat message that this problem could be solved encouraged greater involvement by members of the community—especially since up to two-thirds of infected Asian Americans who are infected are unaware of their disease and the potential for liver cancer. SFHBF’s “B a Hero” campaign was built around the idea that addressing hepatitis B is a heroic cause and that “we,” everyday people, can make a difference.

Another successful strategy involved shifting the paradigm of the disease away from the impression that it is a death sentence by refocusing attention onto solutions such as vaccination and treatment. Thus, the taboo against discussing “bad news,” especially news related to death, was subverted by the message that by working together the community can prevent hepatitis B disease and liver cancer. Community activist Mary Jung said this gave participants a positive outlook: “Isn’t it nice to work on something that’s preventive? … Instead of always raising money for research like for cancer, or something like that.”

Many respondents to my surveys cautioned that it has been easier to destigmatize hep B among Asian Americans born or raised in the U.S., compared to those who are first-generation adult immigrants. But it appears that the San Francisco campaign, by having U.S.-born Asian Americans as leading figures, was able to communicate across the generations to these adult immigrants. And in establishing this precedent the campaign also broke new ground.

Even though this landmark campaign occurred over a decade ago, its lessons continue to resonate. The San Francisco campaign was culturally appropriate. It ran the first major U.S. market ad campaign featuring all Asian American models. Ethnic and general media campaigns were closely coordinated in five languages, but primarily in English and primarily through general market outlets. In addition to getting the cultural aspects right, the campaign used the right messengers and offered the right sorts of messages.

All told, the San Francisco campaign provided a model for communicating and organizing around health issues in the Asian American community—or in any community suffering from a stigmatized illness or condition.

Send A Letter To the Editors