Hawai‘i has a mixed record of welcoming migrants, but even its best efforts are now being stymied by a federal government that is working against those who wish to come to the state, said panelists at a Zócalo/Daniel K. Inouye Institute “Talk Story” event in Honolulu.

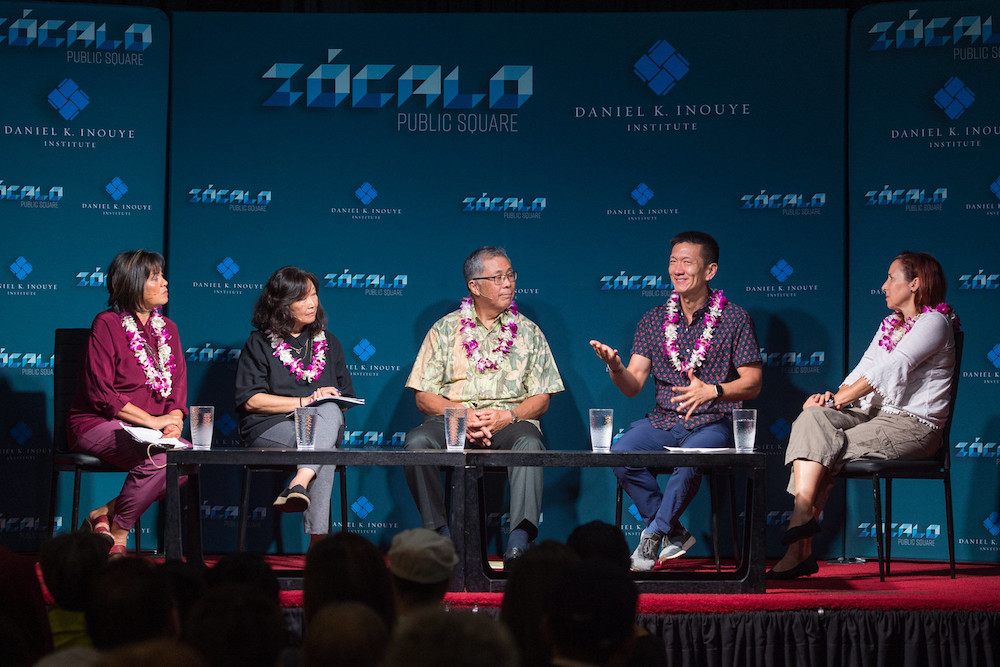

The panel discussion, titled “Does Hawai‘i Welcome Immigrants?” and held before a full house at Artistry Honolulu, drew together a Hawai‘i-born historian of immigration, a leading immigration lawyer, a refugee services professional, and the state’s former attorney general.

Under questioning from the moderator Catherine Cruz, host of Hawai‘i Public Radio’s “The Conversation,” the panelists said that, while Hawai‘i could do more to welcome immigrants, the recent actions of the Trump administration and the conservative U.S. Supreme Court make it a challenge simply to protect the migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers already here.

Clare Hanusz, an immigration attorney, said she would give Hawai‘i a C+ or B- in its efforts to welcome immigrants. She noted that the state has created driver’s licenses for unauthorized immigrants, and guaranteed in-state tuition at the public university for all residents, regardless of immigration status. The state has not been a target for federal immigration raids, she added, and the state’s people have not erupted in an anti-immigrant backlash, as in other states. She suggested that the fact that native Hawaiians and other residents have their own experiences with discrimination may make them more open.

“I think that native populations understand that people get screwed all over the world, and so they don’t begrudge people who are trying to save their lives and find a way here,” Hanusz said.

But she also noted that Hawai‘i has not designated itself a sanctuary, and that the state government and localities don’t provide legal assistance for people in removal proceedings, as some other states do. She also said that people in the islands should be more vocal and more informed. She suggested the audience attend immigration court hearings in Honolulu’s federal building to see a “strange system” that is making it increasingly difficult for even law-abiding people who serve their communities to remain in the country.

“There have been victories in keeping families in Hawai‘i together, but they are getting fewer and fewer,” she said.

Yale University historian Gary Okihiro said he saw today’s immigration restrictions, which are tougher on nationalities considered undesirable for reasons of race and religion, as strong echoes of the past. He recounted in detail how modern Hawai‘i has been transformed into a multicultural place through immigration, from Europe, China, Japan, Korea, the Philippines and Micronesia, and other countries.

But beginning in the early 20th century, Okihiro said, Hawai‘i had to live under restrictive U.S. laws that targeted people of Asian heritage. And Hawai‘i residents have often been split about welcoming migrants, who can be valued for their work but feared for their impact on land and culture. Today’s “dehumanization of immigrants has a long history,” he said.

Former Hawai‘i attorney general Doug Chin, who led the state’s legal challenges to President Trump’s ban on visitors from Muslim majority countries, said that today’s climate is especially difficult because the highest officials in the federal government, including a majority of the U.S. Supreme Court, refuse to acknowledge the obvious: that new immigration restrictions are unconstitutional and based in prejudice.

The Trump Administration’s ban on U.S. travel by people from several predominantly Muslim countries was preserved by a 5-4 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that saw the conservative justices defer to the president, and thus ignored Hawai‘i’s own preferences on immigration policy. “[The president] is calling for a total and complete shutdown of Muslims coming into the United States … and the five people in the majority were able to gloss over that,” said Chin, who added that the case, along with his mother’s recent passing, had prompted him to have long conversations with his father about his parents’ experiences as immigrants from China.

Recently there have been cuts into the services available to refugees, asylum seekers and other migrants, said Terrina Wong, former deputy director of the Pacific Gateway Center, which assists refugees from overseas in resettling in Hawai‘i. Under the Trump administration, the number of refugees allowed to enter the country had declined from 75,000 annually early in this decade to just 18,000. And the federal funding that her center depended upon has ceased.

Wong also raised another issue, in response to questions from Cruz and from the audience: conflict between Hawai‘i residents and migrants from the “compact nations” of the Pacific, in particular, Micronesia. She said that “cultural misunderstandings” had led to difficulties, and she criticized the state government for, a decade ago, making them ineligible for the state medical services that many need.

“We could do a lot better with our Pacific neighbors,” she said. “We have talked about better preparing Micronesians before they come.”

During a question-and-answer session, members of the audience asked about economic exploitation of migrants, about preparations for future waves of migrants, and about how U.S. policy displaces people around the world.

One questioner asked plaintively why more can’t be done to stop the separation of child migrants from their families, as well as mistreatment of children by federal border and immigration authorities.

In response, Chin, the former attorney general, noted that immigration and international law is a slow process. And Hanusz, the immigration attorney, said that stopping such abuses may not happen in the courtroom, but will involve stronger protests.

“We should all be in the streets a lot more,” she said. “It’s criminal what the United States is doing. We’re all in a little bubble here in Hawai‘i, we’re away from the border … But it needs to get challenged.”

Send A Letter To the Editors