Picturing Blood and Kinship

After Eunice San Miguel Recovered From Cancer, She Painted Her Relationship to Her Family and Her Body in a New Way

On the morning of December 9, 2017, I was driving north on the 110 Freeway in downtown Los Angeles when I received a call. It was the doctor I had seen the night before after I noticed bruises appearing in odd places on my body. Hearing the sounds of traffic in the background, she asked if I could pull over. She had some news, she said.

That was the first of many times I felt a tingly feeling of dread all over my body. As I waited for her to call me back, I felt conscious of each breath, each heartbeat, each hair, and pore. It was as if my senses were heightened, and my body was preparing for a fight.

I was a healthy 32-year-old. That Friday morning my mind had been focused on the painting I had been working on, hanging out with friends, and doing some Christmas shopping. But I realized at that moment that everything was about to change.

After the second call, after letting myself cry for a good while, I turned around and drove back home. The hardest part was explaining to my family why I wasn’t going to work: All of my blood counts were abnormal, I had to say; I was being referred to a hematologist—a doctor who specializes in blood disorders—that afternoon.

I didn’t let anyone come with me to the appointment. I didn’t want to burden them with what might happen, but I also did not want to feel responsible for anyone else’s feelings. I thought, wrongly at the time, that I had to face this on my own.

The severity of my diagnosis hit during that first bone marrow biopsy. Even though I was numbed up, I could feel the pressure on my pelvis when my doctor put her whole weight on my body as she tried to scrape a sample from the center of my bones.

I was diagnosed with Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL). It was important, I was told, that chemotherapy start right away. I remember being reassured that APL, once the most aggressive and deadly Leukemia, was now the most curable. Although that was nice to hear, it didn’t really mean anything to me at that moment. Cancer was still cancer.

I like to be in control, and I like to get things done. It’s part of my personality: When I want to do something, I know I can rely on myself to get it done. And I’ll do it. So at that moment, to realize I no longer had control over what was happening with my body was disorienting. I felt betrayed and blindsided by my body—and by my blood.

They wheeled me to a chemotherapy clinic right next door, where other patients were receiving their treatments. I remember the faces of patients and nurses who turned to look at me. My eyes were puffy from crying, my hair was a mess. I’m sure I looked terrified. I saw a lot of empathy in their eyes, but I couldn’t reciprocate or respond to their kindness. Usually, when someone smiles at me, I smile back, but I was too miserable to engage at that moment.

I was admitted to the UCLA Ronald Reagan Hospital, where I stayed for 25 days. My time there was the worst part of my experience. I was trying to come to terms with my diagnosis while going through the extremely intense medical treatment. It was sensory overload. In the beginning, they woke me up every two hours to check my blood. All the beeps, all the sounds, the lights, the uncomfortable bed, everything that I wasn’t used to—it was just terrible. But comfort wasn’t the priority; they were trying to keep me alive.

When I first was diagnosed with APL, I’d resisted leaning on others. While I was in the hospital, though, I realized I had it all wrong. My family and friends became regulars around my hospital bed. My mom, in particular, stayed with me every night I was an inpatient.

Strangers also came to my aid. I am forever indebted to people who took time out of their lives to donate the blood products that saved my life, allowing me to stay healthy while the chemotherapy did its job.

Then I was discharged and received outpatient chemotherapy. For four weeks, I’d go in Monday through Friday for infusions. I’d have a month off, and then repeat the process again, for a total of eight months.

My dad went to all my infusions with me. The few times he wasn’t able to go my brother went instead. It was like having a job. Every morning, I’d wake up at 6 a.m., and eat breakfast so we could get there around 7:30. They did blood tests, and checked how I was doing every Monday. They’d also do an EKG just to monitor my heart because one of the drugs can be really hard on it. If I was good to go, I had an infusion, which took about two hours, with the prep time and the other thing they had to give me added in. It sometimes took longer than that, and I’d fall asleep. Sometimes I’d draw or knit or crochet or embroider to pass the time, but mostly I’d just try to sleep. It was usually lunchtime—1:00 or 1:30 p.m.—by the time I’d be allowed to leave.

Once I started responding to the medicine, and my body started to heal, I got a little bit calmer with the whole situation. I just treated it as, “oh, well this is what I have to go through, I just have to do it”—just like if I were to have a job or have a project due or a painting due—if this is what I have to do, I just have to do it.

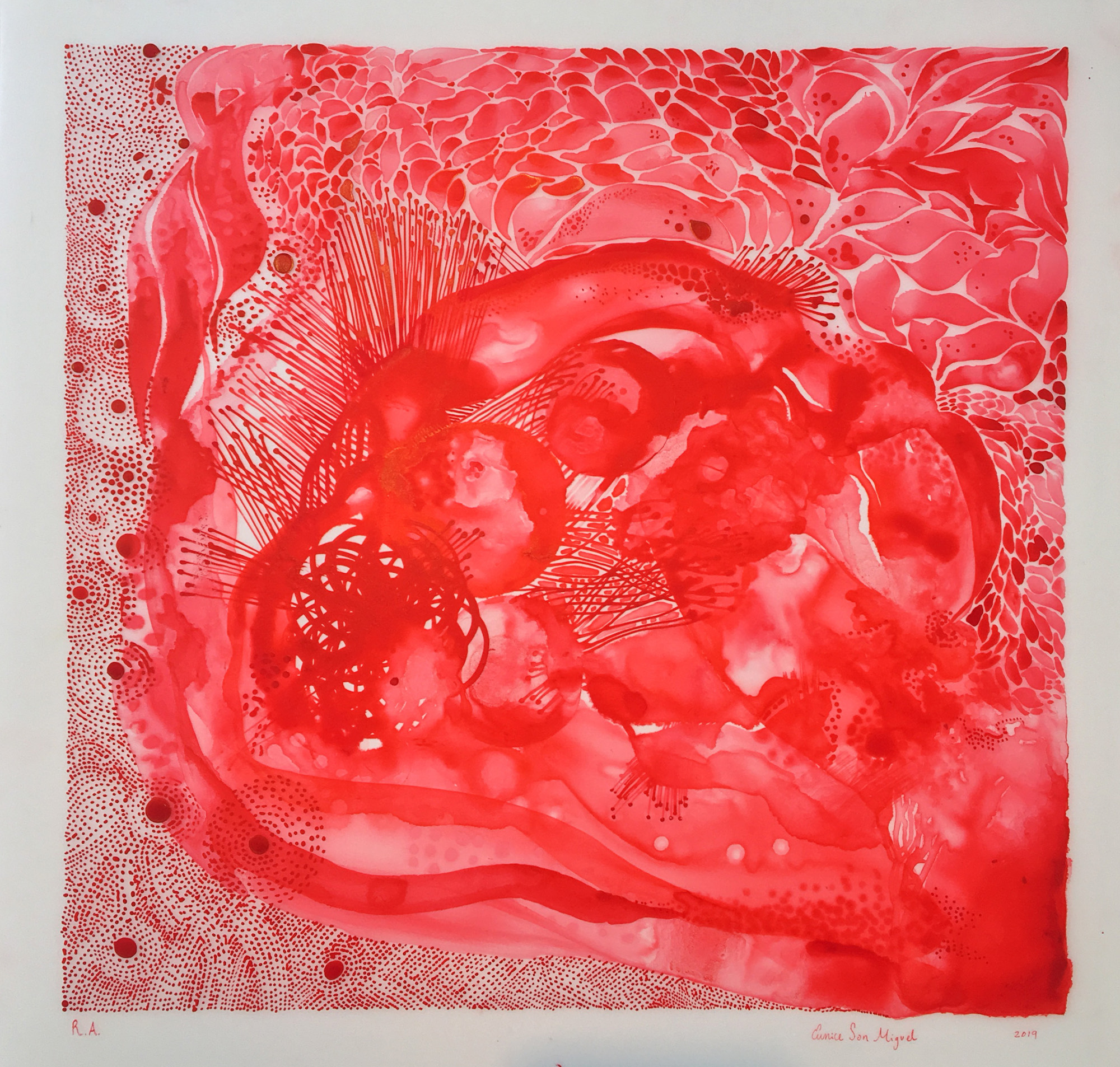

When I finished treatment and my cancer was in remission, I was invited to be part of a four women group show entitled “KIN” at the Center for the Arts in Eagle Rock along with artists Frieda Gossett, Ranee Henderson and Ming Ong, who also curated the show. Each of us was asked to interpret what kin meant. And as I thought about it, I decided to do something on my treatment and my family’s support and care throughout it.

I usually do very figurative work. Figurative can mean literal: It’s a representation of something. If you draw a figure, the viewer sees it as ‘a figure,’ that can’t be mistaken for anything else. But I started doing red paintings with red ink. The art was abstract, which is odd for me to do—dots and dashes and lines and circles—just the shape, basic shapes. But it felt like getting back to the basics, almost like relearning things about myself, and about how I experienced life. It felt less restricted, more free. The red, I realized, also looked like drops of blood.

As I worked, I started thinking about my family, and how they supported me while I was there. Each of the six large red paintings I did came to represent a particular family member.

I did another group of paintings about the 110 infusions of the chemotherapy drug, Arsenic trioxide, that were needed to save me. I made 110 smaller paintings: one to represent each infusion that I had. Some of them are representational, some are portraits, but the majority of them are abstract. There’s no beginning or end with those; just however I was feeling at the time.

This collection of work gets at what was happening to my body, with all of these blood cells, and platelets, and hemoglobin, what have you—all the parts of blood. Healing, and getting better, and not only from the drugs, I think, but from my family, whose support also helped me heal.

This association might not be noticeable to anybody else, which I don’t mind. I like people projecting their own interpretation and seeing what they want to see in the painting. I love that about art. You make your own connections.

Send A Letter To the Editors