When Sewers Were New, Clean, and Amazing

Archival Photographs Reveal an Engineered Labyrinth of Civic Optimism

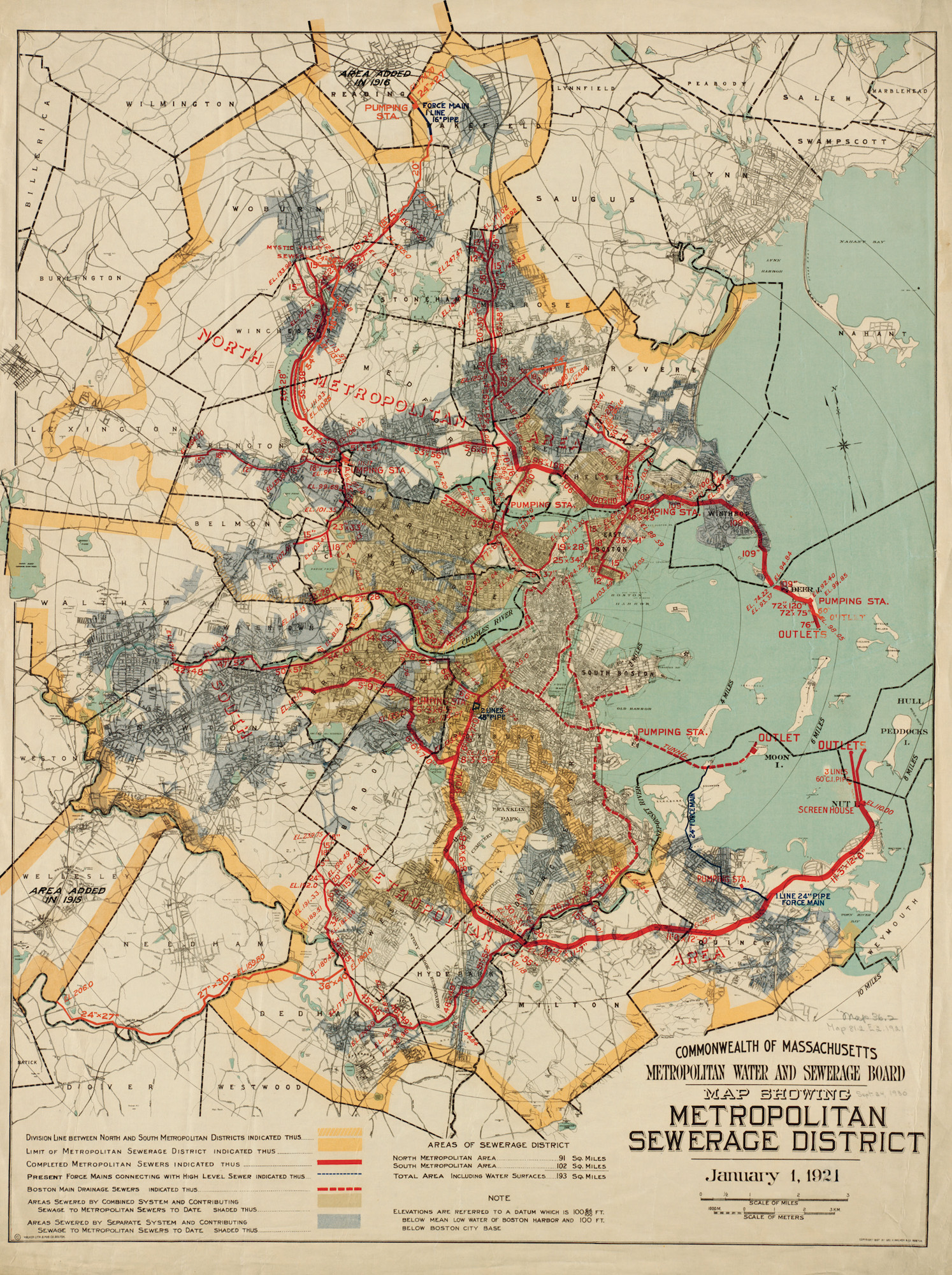

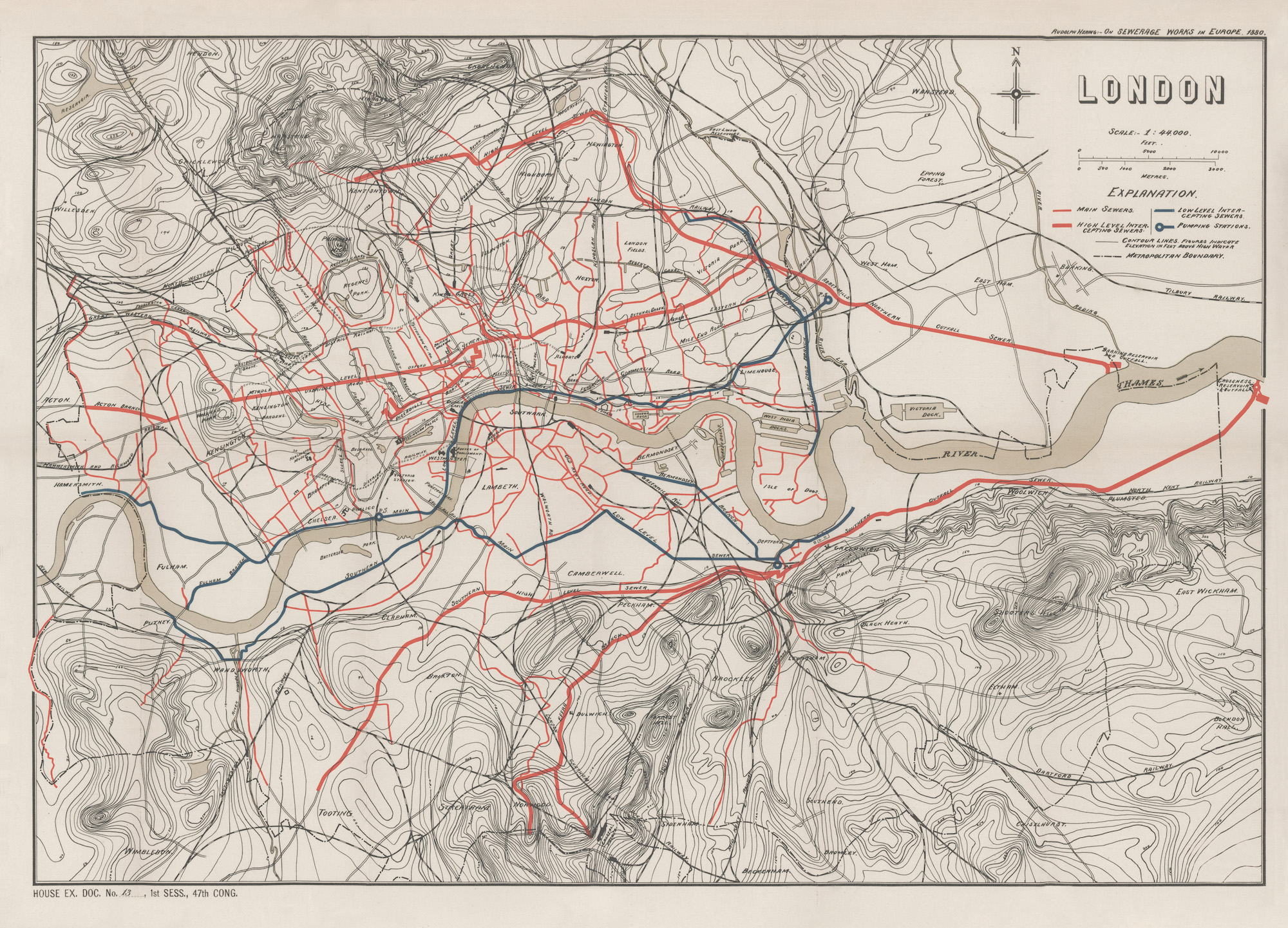

Below our city streets lies an ad-hoc world of subterranean tunnels and pipes. The oldest are brick and concrete sewers that once carried waste streams in one direction, rainfall overflow in another. Today, these waterways must contend with newer sewers, subway tunnels, power lines, and fiber-optic cables. But in the 19th century, these labyrinths were the only man-made things that existed below ground.

Archival photos reproduced in Stephen Halliday’s An Underground Guide to Sewers give us a rare view of these sewers of the past, as they looked to the people who engineered, built, and maintained them.

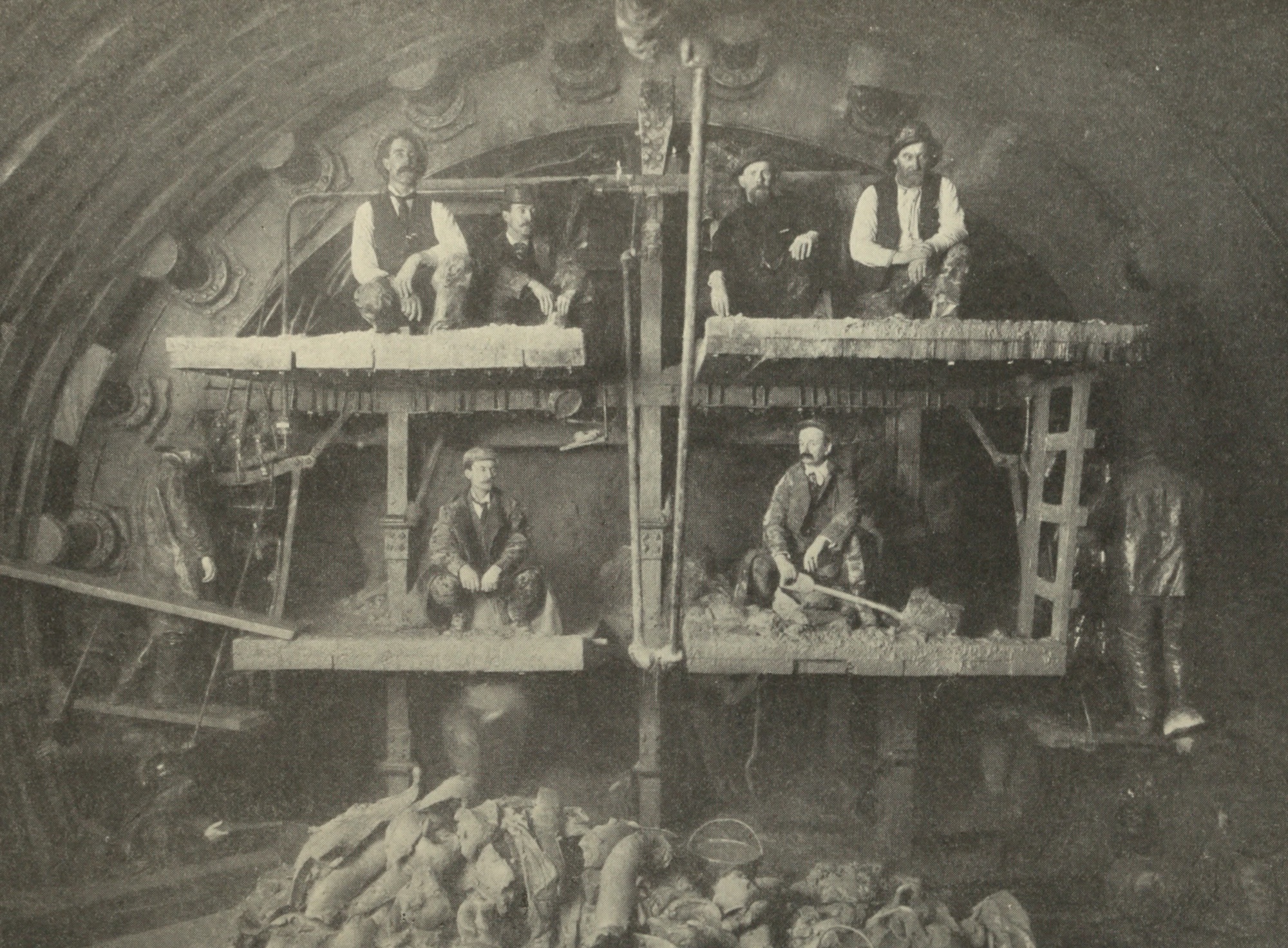

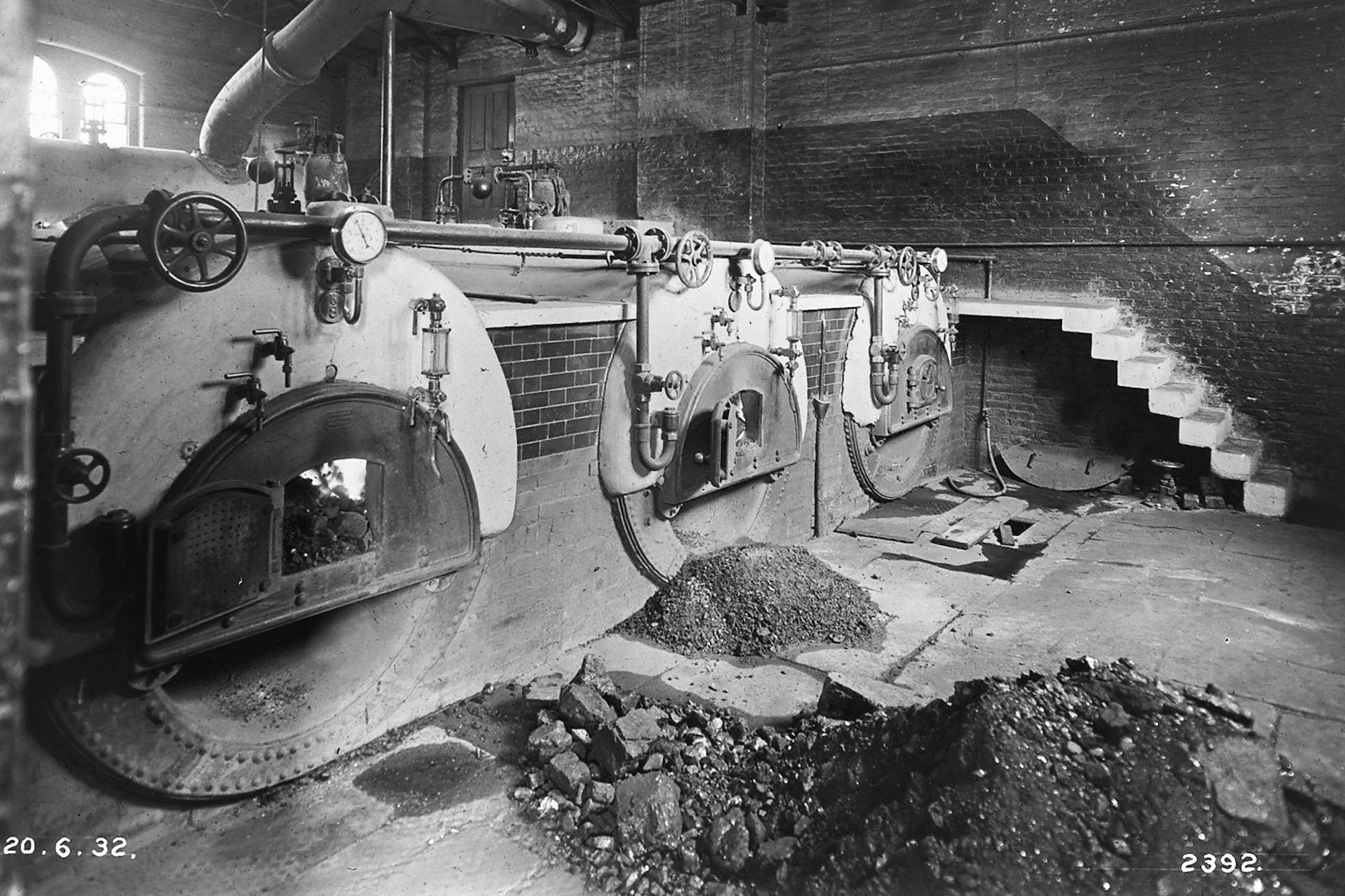

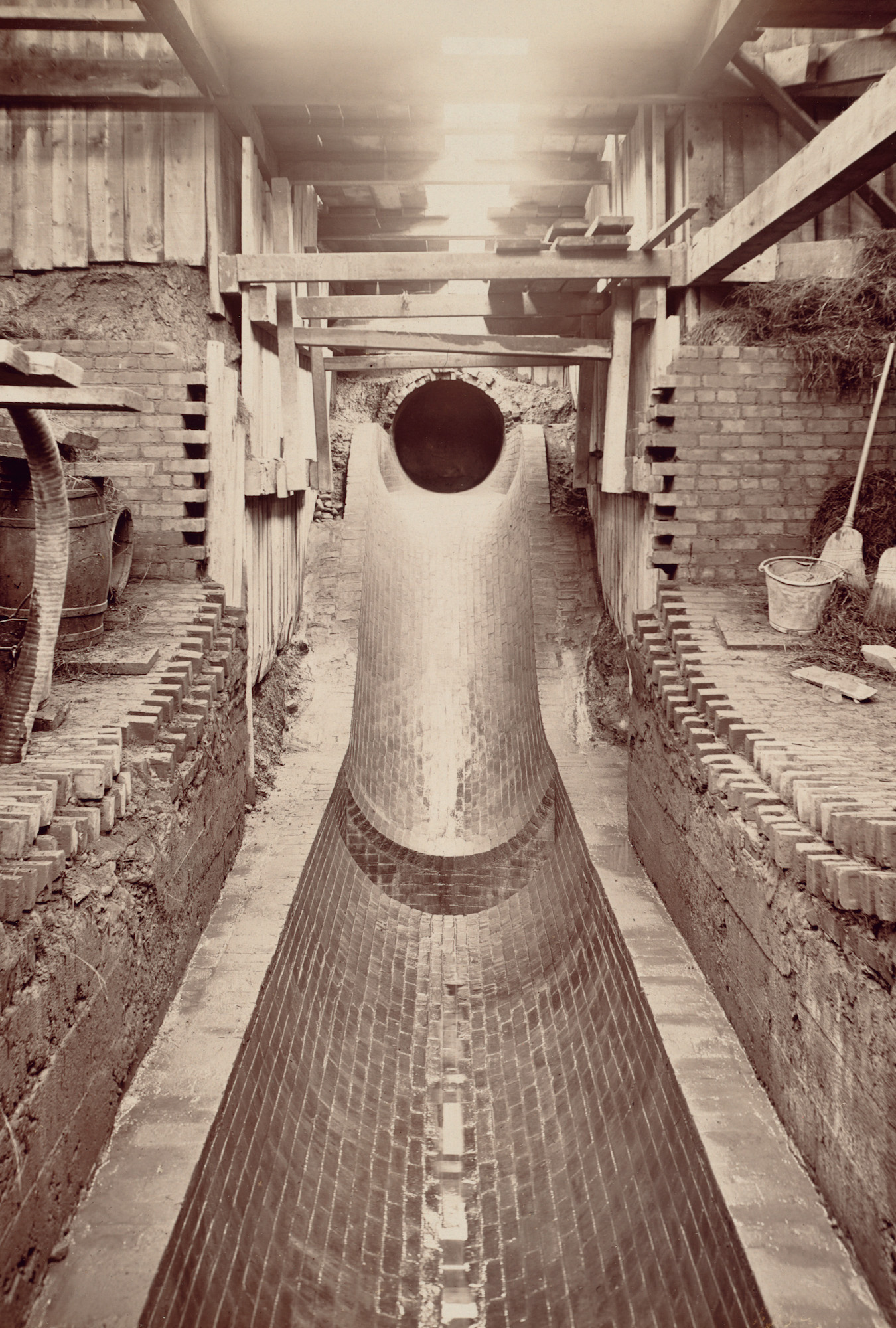

Most of these photographs—dating from the 1880s to the 1940s—show new construction; the before without the after. Pristine iron bars free of rust, walls too freshly mortared to settle and crack, cement yet unstained by water and waste. Older photos show brick-lined culverts, each brick having been laid by hand.

These images are evocative, sometimes beautiful, appearing like black-and-white outtakes from a forgotten film noir. Storm drains appear as volumes of space, empty by design most of the time. Circular and oval tunnels lead from crawlspaces to caverns beneath reinforcing arches. Concrete corridors and junctions, absent any signage, make one wonder what would have happened if Robert Frost’s traveler had gone underground.

But there’s more to these spaces than their cosmetic wonder. These are, after all, not only sites for the flow of waste; they were also places of work. The men photographed in Victorian coats or Depression-era caps and vests do more than provide scale: they remind us that every sewer tunnel started as a noisy construction site. Imagine the human and mechanical din as rocks were carted or bulldozed away, dozens of workers wrangling stone and earth to fit engineers’ specifications.

Sewers were—and continue to be—the great enabler. As industrialization drew people to the city, those people, in turn, made new demands on water and waste systems. That’s why most of the projects pictured here were at capacity soon after completion. Perhaps that knowledge also imbues these photos with a sense of optimism; designed to solve problems, the sewers continued to work, unobtrusively, from their hiding place, to meet ever larger demands.

With this collection, we get to appreciate today what most people didn’t get to see then. It’s a privileged look at the triumphs of industrial-era infrastructure, but it’s also only one chapter of the narrative. What is left to the imagination is how these underground spaces have since been transformed: the aging materials replaced, the time that’s elapsed, overwriting the glory of a feat of engineering.

Send A Letter To the Editors