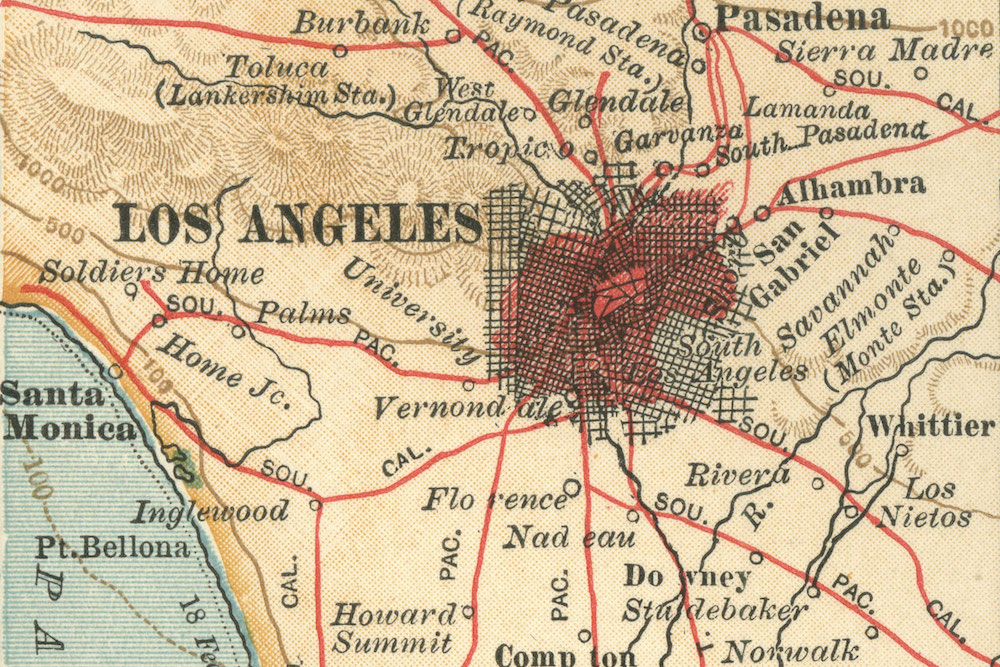

Map of Los Angeles, California, circa 1900, from the 10th edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Courtesy of the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

California is finally getting the local government apocalypse it has long needed.

And, thankfully, it’s going to be even worse than I had hoped.

For the record, I love and revere local government. In most of the world, it’s the most democratic, participatory, and effective level of government, and it deserves to be the most powerful and best-funded.

But in California, local governments are too weak and too small to be of much use. Why? There are simply too many of them. And so, for the past decade—in columns, speeches, and a book I co-authored—I have pined publicly for an “extinction event” that would kill off thousands of California local governments. Now COVID-19 is fulfilling my awful wish, causing declines in local tax revenues so steep that many cities, counties, and school districts may never recover.

Heartless as it may seem, the only way to save local government in California is to eliminate some local governments.

Our ship of state is barnacled with governments. In addition to the state, with its hundreds of agencies and commissions, we have 58 counties, 482 cities, 977 school districts, 72 community college districts, and nearly 5,000 special districts, governing everything from mosquitoes to cemeteries.

Taken together, all these governments resemble nothing so much as San Jose’s Winchester Mystery House, with an incoherent design and an overabundance of rooms that produce feelings of frustration and futility.

Our myriad local governments struggle to come together to solve regional problems like crime, transportation, or economic development. Indeed, they usually get in each other’s way. Citizens are represented by so many different governments that neither they, nor our shrinking local media, can monitor agencies’ behavior. With so little scrutiny, our local governments produce corruption, unsustainable retirement benefits, and other fiscal messes.

Our messy conglomeration of governments doesn’t represent the people’s will. Instead, it saps their trust. And it is this distrust of local government that has led Californians to limit the powers of local officials—especially the power to tax, via Prop 13 and related ballot measures. The result is that our city councils and school boards are among the weakest in the U.S. And developers and public employee unions exploit local governments’ weakness to suck out most of their money, leaving few resources, even in good times, for parks, libraries or arts.

Local government weakness also has centralized California power at the state level. Our cities, counties and school districts spend much of their time begging for cash in Sacramento, where local governments are the biggest lobby.

COVID-19 only deepens this dysfunctional dynamic. Our local governments lack the resources or expertise to decide how to respond to the crisis by themselves; Sacramento makes the big decisions. And with financial support slow in arriving from the federal government, local governments are already cutting services and laying off employees. Local bankruptcies of cities, and state takeovers of school districts, are now on the horizon.

In all this pain lies great possibility. The local apocalypse is so big and that every local government may need a bailout to survive. But there are simply too many governments, and too little money, to save them all. In this moment, we need two enormous changes in the nature of our local governments.

First, we will need to have fewer of them—that’s the extinction for which I pined. Second, we must make remaining local governments more powerful and resilient, so they can give us more in good times, and hold up in future crises.

To do these two things requires confronting a great California curse. Yes, we have the economy, size, and population of a large nation—we’d be the 35th most populous on Earth if we were independent (something Governor Gavin Newsom’s highly publicized brag that California is a “nation-state” acknowledges, in a backward way). But because we’re a state within a larger country, we don’t have our own regional governments—our own states—like real nations do.

We should. Our regions—the North State, the Bay Area, the Central Coast, Sacramento’s Capitol Region, the San Joaquin Valley, the Inland Empire, greater Los Angeles, and greater San Diego—have the size and character of American states. And in our daily lives, we Californians are really citizens of those regions. Our economies are regional, our sports teams have regional fan bases—and our biggest problems are regional. But, unfortunately, instead of having powerful regional governments, we’re split up into tiny shards of local governments instead.

Let’s fix that, by allowing California citizens to establish regional councils—an idea first suggested by California’s constitutional revision commission in 1996. These regional councils could form plans to consolidate our local governments and build real power.

A good start would be folding our thousands of special districts into existing city and county governments. Fiscally weak local governments could be merged into stronger ones. It also would make sense to combine small, contiguous counties, cities, and school districts.

My home county of Los Angeles, with 88 cities, is ripe for this. Do we really need both an El Monte and a South El Monte, a Covina and a West Covina, a Pasadena and a South Pasadena? Artesia, Cerritos, and Hawaiian Gardens already share one school district—why not a City Hall, perhaps with Lakewood and Norwalk as well?

To avoid having newly combined cities become larger versions of our current local weaklings, consolidation must be accompanied by restoring local government power—above all, the power for local officials to tax whatever they like. Local governments would then have control over their fiscal destinies, and could provide better services and more stable employment. In each region, local governments should jointly enact taxes to address regional concerns like transportation, public health, economic development—and disaster preparation.

More powerful local governments would be more democratic and accountable. Watchdogs are more likely to emerge when governments have more power to reach into our wallets. These newly consolidated governments also could more easily eliminate of outdated programs, and produce more responsive, technology-based systems for providing services.

“We continue to provide [government services] without adequately re-examining their fit for the world we live in today,” former Santa Monica city manager Rick Cole recently told the Planning Report. “If we were starting from scratch today, we would design a government that looked more like the iPhone than the rotary phone.”

One blessing of this terrible pandemic is that we can redesign our nation-state. The politics are more favorable, too. The statewide interests that protect centralized state power—our labor unions and corporations—are also reeling from the effects of COVID-19. Any bailouts for them should be conditioned on their support for empowering local government.

The local apocalypse is here—whether we wanted it or not. Let’s make the most of it.

Send A Letter To the Editors