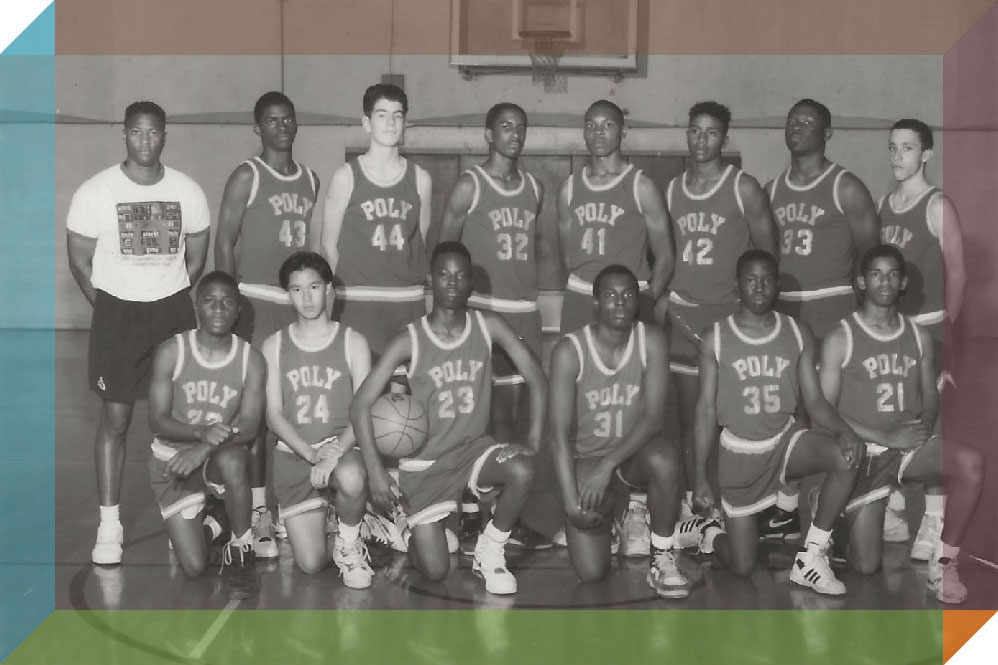

Author Ky-Phong Tran (#24 front row) played basketball at Long Beach Poly High School, once ranked the #1 sports high school in America by Sports Illustrated. Courtesy of the author.

Like any proper Southern California basketball story, this one starts with Magic Johnson.

It’s 1986, and I’m 11 years old, living on the north side of Long Beach. My TV has two dials and two telescoping antennas. I randomly turn on Channel 9, where a Los Angeles Lakers game is playing (back when games could be seen for free). I watch as Magic comes down on a fast break in Inglewood, looks straight southeast at me in Long Beach, and then throws a no-look pass to James Worthy streaking down the right side of the court for a swooping dunk.

A few plays later, Magic—somehow both the tallest player on the court and the best dribbler—rebounds the ball, and in three dribbles, covers the entire court. When he is cut off on his drive, he disappears, spinning full speed the other way in a balletic pirouette and laying the ball up in a swish as soft as a fireman handing a baby off to her mom.

Immediately, I said to myself: I want to do that.

I had no business falling in love with basketball the way I did. My family of five were refugees from Vietnam. We didn’t do after-school activities, summer camps, or organized sports. My brother was a visual artist. My sister played piano and was a good student. No one played sports. Heck, no one even watched sports. But after witnessing Magic orchestrate that ’86 Lakers fast break like a symphony of bodies, I meekly asked my dad for a hoop in our driveway.

I was shocked when he agreed. But of course, he did it in the most Vietnamese of ways. He built the court himself, buying a rim, attaching it to a backboard of scrap wood that he had cut himself, and mounting it to our garage with two Frankenstein-like steel bolts. Little did I know that that orange ring and cheap backboard would develop a 34-year-and-counting relationship with the game.

I’m not sure there’s a more meritocratic place in the world than a basketball court. As a person of color in America, you are judged every day. There’s a long list of places you will discover you are not welcome. But on the court, at least in good games with knowledgeable players, you earn your place. As a 5’7” Vietnamese American in a game of giants, I learned this in spades: If you can play, you can play.

Amidst the squeak of rubber sneakers and the chatter of trash talk, basketball is actually a silent language. A small ripple of your fingers says “I’m open” without announcing it to the world. A subtle head nod signals a stealthy cut to the basket. A thumb point and a smirk mean “This guy (or girl) can’t guard me.” Off the court, I associate the game most with the sound of life-affirming laughter. Have there ever been more fun and shenanigans than on the long bus ride home after a far-off tournament? I mean, who knew you could grow lifelong friendships by insulting people’s mothers?

I didn’t need youth park leagues, YMCA games, or travel ball to learn how to play. I had older cousins, and they taught me the game. They played with great skill and the even greater ferocity of fatherless Vietnamese boys whose dads had died during war. They took me to play pickup games against older players from the get-go. My first “coaches” were the grown-ass men whom I competed against.

Beginning in high school, I had quality coaches, all Black men, who not only taught me the skills and strategy of the game but also—because I was often the only Asian kid in the gym—the confidence and moxie needed to be on the court.

You would think that playing in the basketball hotbed of Southern California—and at two high school programs (Long Beach Jordan and Long Beach Poly) that featured dozens of future college and professional basketball players—I found my greatest competition in organized high school or travel ball games. While those games featured talent and skill, the most intense games I’ve played in my life were actually pickup games. Having played all over the world, including at famous spots like Venice Beach, UCLA Men’s Gym, and MacArthur Park in Oakland, I’ve found pickup games all have the same thing in common: No one wants to lose. The reward for winning is not a trophy, it’s that you get to keep playing. There’s no better feeling than leaving a court after holding it all night and having guys beg you to stay so they can keep trying to beat you. (Winning a few games, scoring on a local, and getting a dap afterward at the most well-known outdoor court in the world, Rucker Park in Harlem, is a close second, though.)

I live in Torrance now, where I’ve coached a number of my two sons’ basketball teams. It’s endearing to see preschoolers try and dribble a ball that seems half their size. I also love hearing “Hi, Coach” from former players in the neighborhood, and I’ve saved every card thanking me for teaching the game with joy and positivity. (I promised myself I would never yell as a youth coach and I’ve kept that promise: One, it’s not a good look. Two, it doesn’t work.)

Author Ky-Phong Tran (top row, right) gives back to the game by coaching the next generation of basketball players (including his son) on the FOR Razors based in Torrance, California. Courtesy of the author.

For two years, my oldest son has played on a year-round team I coach in a historically Japanese, and now predominantly Asian American, league. I was hesitant to make such a big commitment at first, but the allure of coaching the same players year after year convinced me to sign on. There are ten third-grade boys on the FOR Razors, some skilled enough to make three-pointers and perform crossover dribbles, and some who struggle with layups and catching the ball. Coaching the games is enjoyable but the true thrill I get from it is seeing them improve and develop at their own rate. A game where all the boys score at least one basket is my favorite.

The team, once a group of strangers, has become a community. When we unite our ten families for holidays, birthdays, and big NBA games, we number at least 41 people. As a Vietnamese American who was estranged from most of his family back in Vietnam, the parties give me a sense of all those epic family gatherings I missed out on due to war and history.

Now in the midst of a global pandemic and recession, our leagues, games, and tournaments have all been suspended. We tried Zoom practices, but they left me feeling empty. A few weeks ago, we started running together to boost fitness and camaraderie. Lately, we’ve begun socially distant shooting competitions.

In Los Angeles County, basketball has been effectively shut down since March. Gyms are shuttered and the rims have been taken down at the parks. But I’m fortunate to have a driveway hoop. It is an expensive splurge with a huge glass backboard and breakaway rim that I imagine my father would have both admired and disapproved of.

In addition to missing the game and my team, I’m also struggling with the everyday challenges we all are currently facing. I’m stressed to the joints worrying about my wife who used to work from home in a quiet and orderly house. I’m worried about my two sons’ virtual schooling and their social isolation. I wake up in the middle of the night grinding my teeth, thinking of the challenge of teaching my own high school English students from afar.

When it all gets too overwhelming, I go to the driveway and shoot the rock. Of course, I am biased, but shooting a basketball could be the most perfect of human movements. When you do it correctly, the ground and your body and the ball and the rim and the ground again, become an arc, a splice of the most perfect shape in nature, the circle. When the ball swishes through, you are a rainbow, your pot of gold the satisfaction that your actions have met your ambitions.

Go try it. Find the rim with your eyes. Square your shoulders. Raise both arms up as if in prayer. Let the energy build from your toes and flow through your body. Release the ball from your fingertips like a wish onto the world. And remember: Shooting a basketball is a promise to yourself, and to do it right, you have to follow through.

Send A Letter To the Editors