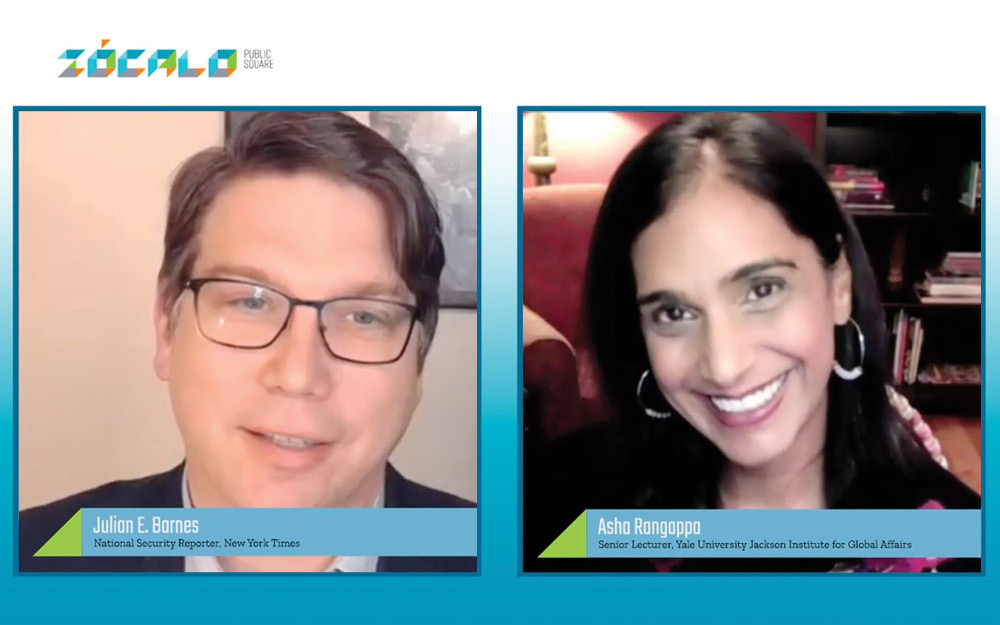

Julian E. Barnes and Asha Rangappa discuss, "What Do We Do Now?"

The title question for Zócalo’s event—“What Do We Do Now?,” posed just days after the historic presidential election of 2020 was finally decided—is also the last line of a 1972 Robert Redford movie, The Candidate. It’s spoken by Redford’s character, who unexpectedly wins a big election—and realizes he has no idea what to do next.

“Unlike Robert Redford,” said event moderator Julian E. Barnes, national security reporter at the New York Times, guest Asha Rangappa, a Yale national security law scholar and former FBI counterintelligence agent, “knows what we do now.”

Barnes then turned to Rangappa and opened the discussion by asking her to take stock of our national security institutions after four years of a Trump administration. How badly politicized are they now, and how hard will it be to undo that damage?

Nothing is broken for good, said Rangappa. However, she expects that the Department of Justice and the FBI, in particular, will take time to walk back from the politicization introduced by this administration.

“I think simply not being the target of vocal attacks by the person sitting in the Oval Office will go a long way,” she said, “but it’s going to be a challenge because under a Biden administration, there may be crimes uncovered involving people from the prior administration, and this once again will place the Department of Justice and the FBI in political crosshairs, even if they are pursuing legitimate operations.”

There’s a tradition in American politics, said Barnes, where the prior administration isn’t prosecuted when a new administration comes to power. He asked Rangappa if she thinks president-elect Biden should respect that history.

There’s too much that needs to be looked at, Rangappa said, pointing, for instance, to the paper trail that led to migrant children being taken from their families. “That to me is in the realm of when we discovered the [George] W. [Bush] administration had authorized torture,” she said.

The best way to determine if the government should take legal action against the Trump administration, she said, is to bring in a special counsel who can figure out what actual violations of federal law were committed. “I know we’re kind of special counseled out,” she joked, however, she added, “you really want someone who is insulated from political influence and has a very clear mandate that they follow.”

“That’s the best we’re going to be able to do short of letting it go, which I don’t think will be an option,” Rangappa continued.

Before the Trump administration leaves office, Barnes asked, is Rangappa concerned about any 11th-hour declassifications?

Yes, she said. What concerns her most is that the administration’s selective declassifications are all a “constant attempt to displace blame on the 2016 interference from Russia to Ukraine or some other entity.” That is one of the goals of declassifications before Trump leaves office, she believes: “to make the case [that] this didn’t happen.”

These 11th-hour declassifications, Rangappa said, will ultimately benefit Vladimir Putin the most. This information not only helps Russia with plausible deniability, she said; it primarily will help the Russians identify leaks and could potentially put sources in danger. “That’s what worries me.”

Looking further ahead, Barnes asked what can be done to prevent the norms that Trump broke during his presidency from being broken again in the future.

Strengthening protections for inspector generals of the intelligence community is one avenue, said Rangappa, pointing out, for instance, that the impeachment proceedings only happened because inspector general Michael Atkinson alerted Congress to the whistleblower complaint about Trump’s communications with the president of Ukraine. “Inspector generals are a vehicle for Congress to learn about misconduct in the executive branch,” she said. “What we saw was an attempt to cut that channel off at the knees by installing loyalists in that position or creating dubious legal justifications for not passing on whistleblower complaints.”

Audience questions piled in for Rangappa, asking her to address everything from whether Trump might attempt a self-pardon to the future of the Department of Homeland Security.

Self-pardon, Rangappa said, “depends on whether Trump is going to be a rational actor or a not-rational actor.” Rangappa also thinks it’s possible the president may step down at some point—“maybe even the day before inauguration”—so that Pence would be able to grant him, his children, and other players, like Paul Manafort and Michael Flynn, pardons. “That I think would be much more airtight,” she said.

Another audience member wanted to know how worried the intelligence community is about secrets Trump could reveal after leaving office. “It’s absolutely a real concern,” said Rangappa, noting the president’s $421 million of debt. “From an intelligence standpoint, he’s vulnerable, and he has valuable information that other countries would be very tempted [by]—and they’d be dumb not to try and exploit.”

One of the last questions of the discussion returned to the intelligence community itself, and how intact it is at this point.

The damage is mostly at the top, said Rangappa. “If there’s one thing we’ve learned of the last four years, the thing that has saved us is our vast bureaucracy,” she said. After all, it was a CIA analyst who blew the whistle on the Ukraine call, and rank-and-file agents who continued the investigation. “Our civil service, our bureaucrats—these are the people that are making our country run,” she said. If a critical mass of people were to exit, then the culture of these organizations might change, but that hasn’t happened. “I think right now the culture of these organizations is mostly still nonpartisan,” she said.

Send A Letter To the Editors