Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California. Photo by Joe Mathews.

If you’re having a hard time processing the scale of death produced by the COVID-19 pandemic, you’re not alone. In the face of mass casualties, many of us have chosen the path of denial, embracing conspiracy theories, resisting public health orders, and falling into anger and anxiety.

So let me suggest a healthier alternative to wrapping your mind around this moment’s carnage. Visit the largest, prettiest cemetery you can find. I recommend the original Forest Lawn, the first of the six Forest Lawn memorial parks, a place sprawling enough to have graves in two cities, Glendale and Los Angeles.

I recently spent two days walking all 290 acres of Forest Lawn-Glendale—the most historic, and Californian, of our state’s cemeteries—and found that it clarified my thinking and even improved my mood.

The place also helped me to put in perspective the full human toll of COVID-19. Since Forest Lawn opened here 114 years ago, in 1906, it has interred 340,000 souls on this property. Under current projections, the United States will experience 340,000 COVID deaths by sometime in January, 10 months after the March lockdowns began.

Those numbers also made me think of Colma, the Bay Area’s lovely and haunting city of cemeteries, just south of San Francisco. That necropolis, after more than a century of existence, is now the final resting place for an estimated 1.5 million people. Worldwide, we are on track to pass 1.5 million confirmed COVID deaths before Christmas.

Such statistics are sobering and tragic. They also reflect a fundamental human failure: We experience individual death intensely, but struggle to recognize death in the aggregate. That’s why we can more forcefully rally together in response to one death—like the police killing of George Floyd—than in response to escalating numbers of COVID deaths scrolling across our screens.

Our myopia is why we need cemeteries right now, and not just as places to bury our dead.

“Cemeteries are not just a place to reflect on the past,” wrote the longtime Forest Lawn chief executive John Llewelyn in A Cemetery Should Be Forever. “They remind us to keep the present in perspective.”

Especially, perhaps, when the present is so frightening.

Forest Lawn’s mission, originated by its early leader and builder, Hubert Eaton, was about putting a sunny California spin on death. An innovator, like so many Golden State institutions, Forest Lawn was the first “memorial park,” the first to ban tombstones (requiring ground-level markers that didn’t obstruct views), and the first to provide all your death needs—a cemetery, crematory, church, flower shop, mausoleum, columbarium, and mortuary—together on one site.

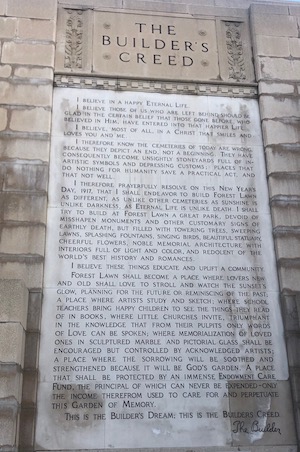

Photo by Joe Mathews.

“I believe in a happy eternal life,” Eaton wrote in Forest Lawn’s “Builder’s Creed” in 1917. “I therefore know the cemeteries of today are wrong, because they depict an end, not a beginning.” To better serve humanity, he pledged, “I shall try to build at Forest Lawn a Great Park, devoid of misshapen monuments and other customary signs of earthly death, but filled with towering trees, sweeping lawns, splashing fountains, singing birds, beautiful statuary, cheerful flowers, noble memorial architecture with interiors full of light and color, and redolent of the world’s best history and romances.”

Forest Lawn has been relentlessly satirized (by Evelyn Waugh in his 1948 novel, The Loved One) and critiqued (by Jessica Mitford in her 1963 exposé, The American Way of Death). Serious types have dismissed it as a “Disneyland of Death.” But at this particular moment, I found visiting the happiest cemetery on Earth soothing, and thought-provoking.

I encountered joggers, bikers, landscape painters, and people walking babies in strollers. From a distance, I listened to a funeral full of jokes and laughter. I heard birds sing as I enjoyed 360-degree L.A. views from the esplanade. A half-dozen people chatted amiably about the weather while admiring “The Mystery of Life,” a sculpture group of 18 human figures gathering around a stream that flows from an unseen source toward an unknown destination.

By its usual standards, Forest Lawn was pretty quiet. Its art museum—which houses an important collection of stained glass, the world’s largest black opal, and William Bouguereau’s 1881 painting “Song of the Angels”—was closed. There were no school field trips on the grounds. Tens of thousands of people, including Ronald Reagan, have been married at Forest Lawn, but during my visit there were no weddings in the cemetery’s three churches, which were locked.

Still, I enjoyed the way the place resembles Southern California in miniature, with its different topographies (windswept hills, cool valleys, a sprawling basin), cultural mishmash (Italian statues, Scottish and Irish churches, and crypts with inscriptions in every modern Asian language), and obsession with being big (Forest Lawn notes that its large wrought-iron gates are twice as wide as those at Buckingham Palace, and the Hall of Crucifixion houses “the world’s largest permanently mounted religious painting”).

Forest Lawn is perhaps the best place in Tinseltown to get close to a celebrity—everyone from Walt Disney to Jean Harlow to Michael Jackson is interred there—though you have to do some detective work, since the staff won’t tell you where they are. I did manage to find the famed early 20th-century L.A. preacher Aimee Semple McPherson, who, in her Divine Healing Sermons, advised, “get alone in the wilderness of quiet and stillness before God.”

I found powerful stillness in the Great Mausoleum, where I chatted with a woman who was looking for the crypt of Paramahansa Yogananda, the Indian guru who popularized yoga and meditation in the U.S. And I laughed at discovering that the crypt of California Gov. Culbert Olson, famous for being an atheist, is just steps away from the mausoleum’s stained-glass reproduction of da Vinci’s “The Last Supper.”

Down the hill from the mausoleum is an older, flatter cemetery section so filled with light it feels like heaven’s front porch. There I walked amid many graves from 1918 and 1919. Most of the people buried in them had died in their teens, 20s, and early 30s, the most common ages of Spanish flu victims.

From there, I headed up to the Court of Freedom, which includes a mosaic reproduction of John Trumbull’s “Signing of the Declaration of Independence” that’s three times larger than the original painting in the U.S. Capitol. I read the text of the Declaration inscribed next to the painting, and reflected on Jefferson’s wisdom in putting “life” before “liberty” and the “pursuit of happiness.”

Death is a constant of course, but the speed of this pandemic is overwhelming us, to the detriment of the living and the dead.

We are in such a desperate rush to get past COVID that we’re trying to ignore its realities. It seems likely that we’ll forget this era as fast as we can.

We shouldn’t ever put the pandemic behind us. We will all need to remember its lessons, to honor its sacrifices and its heroes, so we might see its after-life as a beginning, not an end. Here in California, I hope we will memorialize every last one of our pandemic dead, with a monument that is beautiful and colorful and big, and makes people happy when they visit it.

Send A Letter To the Editors