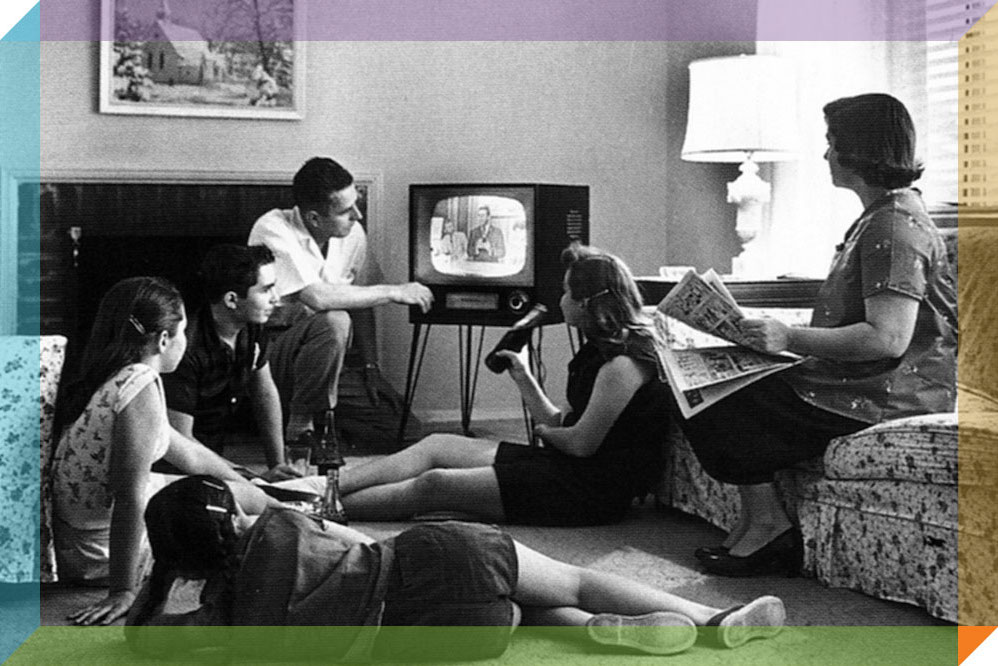

The mood in the room shifts when the TV turns on. Credit: Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

I wish I was watching TV right now. When I’m not watching TV, I like to reflect on all the previous times I’ve watched TV or look forward to the times when I will again.

I’ve held telly as the pinnacle of all possible evening activities for a good few years now. When I’m glued to the screen, slumped out on an oversized cushion because my housemates have bagged the sofa, I never worry I should be somewhere else; I don’t question whether I ought instead to be broadening my mind.

Without a doubt, my best TV-watching experiences took place in 2017, when I was 22, in the English county of Cornwall, in the port town of Newlyn. I was staying at the cottage of a couple named Denise and Lofty, whom I’d never met before but had offered me up their spare room when I moved to Newlyn to research the Cornish fishing industry for my book, Dark, Salt, Clear: Life in a Cornish Fishing Town.

My first night at Denise and Lofty’s place, I was pretty nervous. I’d spent all day on the train, traveling up from London to Penzance, the first to the very last stop on the line. They picked me up from the station and, as we drove along the coast toward Newlyn, I could make out the last few day fishing boats heading back into the harbor, their lights casting galaxies across the darkening water. Neither Denise and Lofty nor I knew quite what to say to one another as we sat in their lounge, plates of buttery baked potatoes balanced on our laps.

But when they turned the TV on, the mood in the room shifted instantly: we relaxed into ourselves, conversation becoming easier because there was no longer a gaping silence any of us had to fill. Lofty asked if I liked the soap Coronation Street. I said I hadn’t seen it before. “Well, you’re going to get to know it pretty well living here, my love!” he winked, and the two of them burst into coarse, gravely laughter, the product of many years diligently spent chain-smoking.

I came to love our evening TV routine. As the light faded, I would appear at the front door, exhausted and smelling strongly of fish, after days spent working on deck of a crabbing vessel or ring netter, which catches pilchards. With the television on and the three of us curled up on the sofas, Denise would tell us stories of the demanding tourists she’d served at the fishmongers where she works, which is a two-minute walk from the ship’s chandlers where Lofty works. (I am often told that “For every one man at sea, that’s five jobs on the land.”)

I believe that the freest exchanges take place when you are not facing one another but rather when your eyes are on something else. It is in that moment that language becomes untethered. Each word is given the space to open outward and drift. For me, this can happen on walks, on benches, in cars with your feet up on the dashboard, while staring out at the sea, and, and my personal favorite, in front of the TV.

British anthropologist Daniel Miller has suggested home is “the place where most of what matters in people’s lives takes place” and “the site of their relationships and their loneliness: the site of their broadest encounter with the world through television and the Internet.” And so, the way we use TV says a lot about us, and our relationships. On that sofa, every wall decorated with paintings of the sea and each surface with a toy fishing boat, listening as the winds picked up and the waves crashed against the harbor wall, we would talk about our lives more honestly than I was used to back home in London. By the time I left, I would consider them a second family.

From Denise and Lofty’s cottage, I then headed down Newlyn’s North Pier to board a deep-sea trawler that would take me away from the Cornish coast for eight days with four other fishermen I barely knew. The Filadelfia (PZ – Penzance – 542) was a 79-foot beam trawler, skippered by a barrel-bellied fisherman called Don. She was built in 1969, the same year man felt the Moon beneath his feet for the first time. Like Apollo 11, the Filadelfia was a voyager, transporting man away from familiar landscapes into the unknown, protecting her crew from the mysterious waters existing just outside her thick, steel, yellow-painted shell.

While out at sea, I learned that a fishermen’s trawler is much more than their place of work. It is where they eat, sleep, dream, smoke, watch telly, and wait to go home. Each vessel becomes a figure to whom they feel deeply connected for the rest of their life.

Every three hours, Don hauled the nets that were dragging along the ocean floor up and we would get to work gutting whatever fish are brought up—mostly lemon sole, dover sole, turbot, bream, monk fish and rays. The crew gave me my own knife, smaller than theirs, with yellow tape twisted around the handle, and patiently taught me how to disembowel each species of fish. Once the haul was over, the men either retired to the cabin down below where we all slept together, or headed over to the galley to smoke and watch TV.

All trawlers have TVs in their galleys. These stay on day and night, providing an unending background burble. On our first night, while the crew polished off my last few chips (you eat like a king at sea: huge, comforting school-dinner meals of beef, steak, sausages, chips, and mashed potatoes), we sat close together, twisting round to face the TV so we could shout answers at The Chase (Don and the crew’s favorite gameshow) and jeer at contestants when they got obvious things wrong.

Peter Collett, a behavior psychologist, suggests that television “buttresses social relationships in the sense that it gives people something to discuss.” The Chase suddenly became the most important thing; we would reference past contestants like old friends, particular episodes where we would, as a team, have beaten “the chaser.” Our TV-watching ritual held us together, especially as the week drew on and we became more tired and homesick. It was a way of feeling connected without having to speak, and a comfort that simultaneously reminded us of home.

My favorite evening of TV-watching on the Filadelfia occurs on our final night at sea. For dinner, we’d feasted on a spectacular roast cooked by Don, the meager size of the galley’s oven and lack of surfaces in no way limiting his culinary ambitions. From the oven, Tetris-like, he produced a steaming tray of golden roasted potatoes, swede mash, Yorkshire puddings, an overflowing pot of cauliflower and broccoli cheese, honey-roasted parsnips set to a perfect crisp, and tender strips of beef.

While we sat nursing our bloated bellies, we found ourselves confronted with Johnny Depp’s eyeliner-smudged and darkly tanned face swinging the wheel of the Black Pearl. There will probably never be a more appropriate environment for watching Pirates of the Caribbean than shoulder-to-shoulder with four fishermen as you drive through the running sea in a wet night. The crew guffawed and slapped the table as the pirates ran rings around the Royal Navy officers.

And when Elizabeth Swann joined the buccaneers, exchanging her corset for a pair of men’s trousers and a sword, I could not help but glance down sheepishly at my fish-stained tracksuit and think of my yellow-stripped knife hanging up on the deck. We watched the film right through, snug from the winds and rains drawing around the boat, the heat from the oven fogging up the galley windows, thinking of the homes we would be returning to the next day.

Truth be told, just before I came to Newlyn, I had stopped seeing the point of television. I was at university and trying to work out what shape my life would take. I’d felt anxious then that everything I consumed should be an additive: something that would help me become a great writer or a great thinker. TV-watching, I worried, had no obvious use to me.

But during my time living with Denise and Lofty, I learnt that the best conversations are not the big ones you are trained to reach for in university, with all those long words with which to explain the world away. The best ones are the small chats that occur during the adverts between TV shows or as the credits roll for Coronation Street. These are the conversations that make you laugh, that don’t have to carry much weight, and that, because they can be silly and forgettable, help to solidify friendships and relationships.

TV-watching enables a particular kind of vulnerability: to sit close to one another and just be present together, without performing, without needing to assert our identities. It is also a portal through to past times. Watching TV allows me to be close to Denise and Lofty again, to be on a rusty trawler in the middle of a raging sea, to remember all those extraordinary things that happened to me in the fishing town of Newlyn.

Send A Letter To the Editors