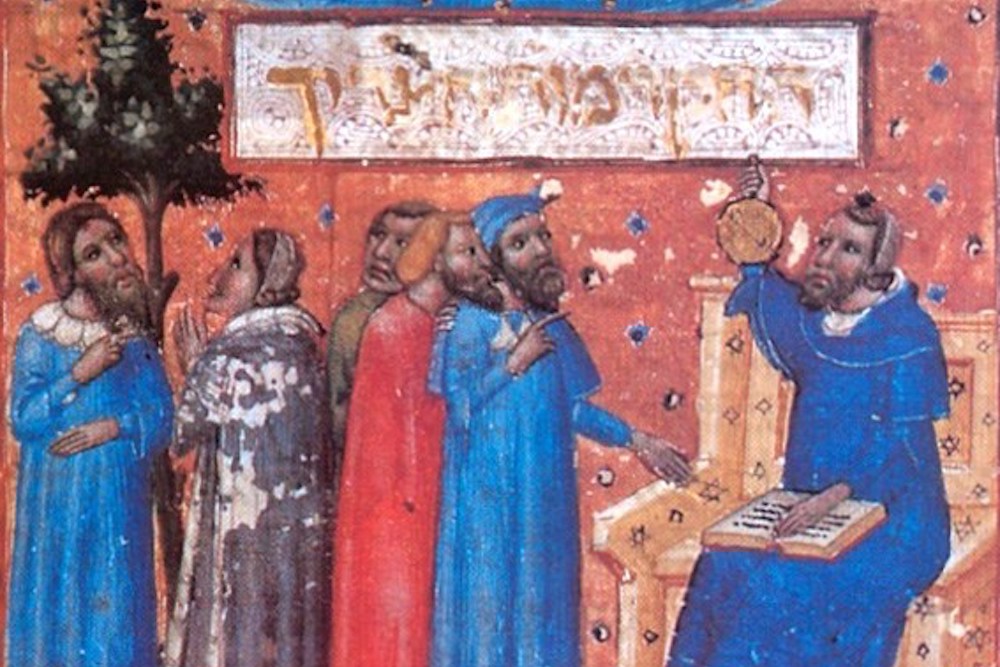

“How does one confess,” asked 12th-century Jewish philosopher Maimonides. “He states: I implore You, God, I sinned … I regret and am embarrassed for my deeds. I promise never to repeat this act again.” Courtesy of Public Domain.

The Biblical story of the Gibeonites rarely makes it into the classroom of a Sunday School or Hebrew school, but the tale has much to say to 21st-century Americans.

The Gibeonites, a Canaanite group, forged a pact with the Israelites when the Israelites were conquering the land—but, after a series of twists and turns, wound up their permanent servants. The Gibeonites became “hewers of wood and drawers of water for the House of my God,” according to the book of Joshua.

The arrangement persisted for a few hundred years, until Saul became king and slaughtered the Gibeonites. The Bible doesn’t offer details of the massacre, but it does record that many years after Saul died, during the time of King David, God punished the Israelites for the great injustice by bringing about a great famine.

After three years of starvation and want, King David was desperate to save his people. He met with the few remaining Gibeonites and asked how he could make restitution: “What shall I do for you? And with what shall I make atonement, that you may bless us?”

This story is one of the earliest recorded examples of collective apology. King David wants to apologize and make restitution for the sins of a generation long dead—for actions that he had no hand in—but he doesn’t know how to do it. Today, similarly, many Americans are recognizing the importance of making long-overdue amends to the people we have injured—and encountering the same sort of unsettled uncertainty.

These are hard questions: How do the descendants of those who committed a historical wrong find the will to apologize, atone, and make restitution to the descendants of those who were wronged? And how do the people whose forebears suffered so greatly find the courage to negotiate such an apology and ultimately accept it?

My deep interest in collective apology has two roots, one planted in years of work as a rabbi and the other planted in years of activism in social movements. Listening to people recount the hurt they experienced, and the harm they perpetrated, sensitized me to how infrequently we use the tools of apology. Some communities see themselves as inheritors of deep, and unaddressed, collective trauma. Other communities acknowledge past wrongs but feel no personal responsibility for them.

Collective apology seemed like the tool to change the stories that communities tell themselves. It was also a great spiritual challenge, which is why I made it the focus of two years of sermons for the high holy days, that time in the Jewish liturgical year known as the “10 days of repentance,” when the difficult practices of atonement and forgiveness occupy our hearts and minds.

My first sermon drew upon the work of David Lambert, a University of North Carolina religious studies scholar. His book How Repentance Became Biblical shows that our contemporary notion of repentance has few antecedents in the Bible, and instead is rooted in rabbinic ideas that came later on. If our ideas and practices around repentance had already evolved once, I suggested, they could evolve again. I framed collective repentance as a new horizon for American society. Many congregants told me the sermon sparked table conversations over holiday meals. I felt I was just getting started on the topic.

My second sermon drew upon the research of Samuel Oliner, a Holocaust survivor and scholar of altruism and collective apology. Oliner wrote about how large groups of people—societies and governments—collectively pursued alternatives to violence and polarization. In his research, he found that altruism, genuine apology, and forgiveness, though difficult to achieve, often led to reconciliation.

Oliner tracked down more than 100 contemporary examples of collective apologies. The breadth and depth of his list shocked me. Oliner was able to point to five noteworthy examples from the 1990s alone.

In 1993, the U.S. Congress apologized to native Hawaiian people for the American overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i 100 years earlier. In 1995, the South African government established the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to hear from perpetrators of crimes during apartheid. In 1997, British Prime Minister Tony Blair initiated an apology to the Irish people for British responsibility in the 1840s Potato Famine. In 1998, Pope John Paul II apologized to Jews for the Catholic Church’s not doing more to stop the Nazi regime during World War II. In 1999, the president of the west African country of Benin came to the U.S. to apologize to African Americans for his country’s complicity in the transatlantic slave trade.

As I studied Oliner’s list, one collective apology caught my attention: a Japanese company’s arduous attempt to apologize to American prisoners of war for harsh labor camps during World War II.

In December 1941, two weeks after Pearl Harbor, Japanese forces attacked the U.S. Army base on the Philippine island of Luzon. Seventy-six thousand troops became POWs; Japanese soldiers marched them more than 60 miles (an episode later known as the Bataan Death March), beating and killing some POWs, while allowing others to die of disease and starvation. POWs who survived were taken to camps in Japan, and contracted out as slave labor to 14 different Japanese companies.

A generation after the war, many people in Japan began to think it might be time to make a collective apology to American POWs. The process dragged on for decades, as Japanese leaders repeatedly issued and retracted apologies, sometimes issuing denials of war crimes and approving textbooks that suppressed the true history. It wasn’t until 2015 that conditions for a successful apology developed, in large part because of a Japanese American named Kinue Tokudome.

Tokudome was born in Japan just after World War II. In her Japanese high school in the 1960s, no one talked about the conflict; it was only after she moved to California at age 26 that she learned about the war. In 1986, when a book by a Japanese author denying the Holocaust became wildly popular, Tokudome became so upset that she spent a year crisscrossing the U.S., interviewing survivors and translating their stories into Japanese.

As she worked, Tokudome met American ex-POWs who talked of their continued hopes for apologies from the Japanese companies that had forced them into hard labor. Sensing an opportunity, Tokudome wrote letters to the companies. Only one responded: Mitsubishi Materials, which had forced 900 POWs to work in the snowy mountains, mining copper for Japanese bullets and submarines.

Collective apologies require an apology broker, someone rooted in the society that committed the act who is empathetic to the suffering of those who were harmed. In the story of the Gibeonites, this was King David, who asked, “What shall I do for you? And with what shall I make atonement, that you may bless us?” In Mitsubishi’s apology to American POWs, this was Tokudome.

Tokudome, in negotiating an apology, partnered with Jim Murphy, an American who had worked as a POW in Mitsubishi Material’s copper mines for captors who instructed, “You work or you die.” Murphy told Tokudome there were three things he wanted to hear in an apology: “I did it, I’m sorry I did it, and I will not do it again.” In this, Murphy identified the three elements of a successful collective apology: admission, regret, and promise. The 12th-century Jewish philosopher Maimonides prescribed the exact same formula: “How does one confess? He states: ‘I implore You, God, I sinned … I regret and am embarrassed for my deeds. I promise never to repeat this act again.’”

Mitsubishi was willing to listen, and after many talks, scheduled a formal apology ceremony for Sunday, July 19, 2015, in Los Angeles. During the ceremony, Mitsubishi executive Hikaru Kimura described the harsh life in the mines, without food, without water, without medical attention. Through an interpreter, he told Murphy, “When I understand the sad truth of the matter, I feel a pained sense of ethical responsibility as a fellow human being. As a representative of Mitsubishi Materials, I apologize to you, deeply.”

Murphy had seen a draft of the statement in advance, but arrived that day still unsure if he would accept the company’s apology. Then, as he watched, seven Mitsubishi executives stood up and bowed at the waist. The bow lasted for 14 seconds. Murphy formally accepted the apology.

I told this story in my second sermon, hoping my community might see an apology issued to Americans as a model for how we might offer collective apologies.

Each of us has been wronged by someone in our lives. We know the feeling of distance, disconnect, and anger that we harbor before granting forgiveness. And anyone who has wronged someone else knows how guilt accumulates until an apology and reconciliation have occurred. We understand the basic process of an individual apology. If we choose not to apologize to someone we have hurt, it’s generally because we can’t bring ourselves to do it—not because we don’t know what an apology looks like.

But the pursuit of a collective apology is more arduous, fraught, and volatile, as past experience—Biblical and contemporary—shows. Trauma and guilt travel through time, and collective apologies, when they happen, generally occur generations after the initial wrong.

A Biblical teaching connected to the Ten Commandments touches on the idea of cross-generational culpability. “God does not remit all punishment,” reads a verse that is repeated in Exodus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy, “but visits the iniquity of parents upon children and children’s children, upon the third and fourth generations.” This idea may be anathema to our modern sense of individual justice, but there is no statute of limitations for societal sin. Iniquity committed at the societal level is indeed born by future generations, who are responsible for taking corrective action. The bridge of collective apology must span two expanses: the sea of society and the river of time.

This second sermon generated more reaction than the first, probably because I tried to bring the concept home. I reminded my community of the many collective apologies that we Jews have received in recent memory, for the traumas of the Holocaust and for historical Christian antisemitism. But then I also said, “As an American, I can imagine collective apologies that we will one day make to Native Americans for centuries of crimes against indigenous peoples. And I can imagine collective apologies we will one day make to African Americans for our society’s foundational investment in slavery. And as a Jew, having spent time in the West Bank off and on over more than twenty years, I can imagine collective apologies that the Jewish people will one day make to Palestinians.”

Those lines triggered productive discomfort. “Rabbi, should we really apologize to all of those groups? This one, of course, but that one?” Collective apology in theory is one thing. Collective apology in practice is another.

And yet I see signs that more Americans are more willing to consider collective apologies for some of the societal sins embedded in our past. Or at least I can say, I am ready to help pursue such apologies. I pray that others are too. And if those of us who are ready keep talking to others about it, perhaps we can add the United States to the list of societies that mustered the courage to take responsibility for the horrors of their pasts.

Send A Letter To the Editors