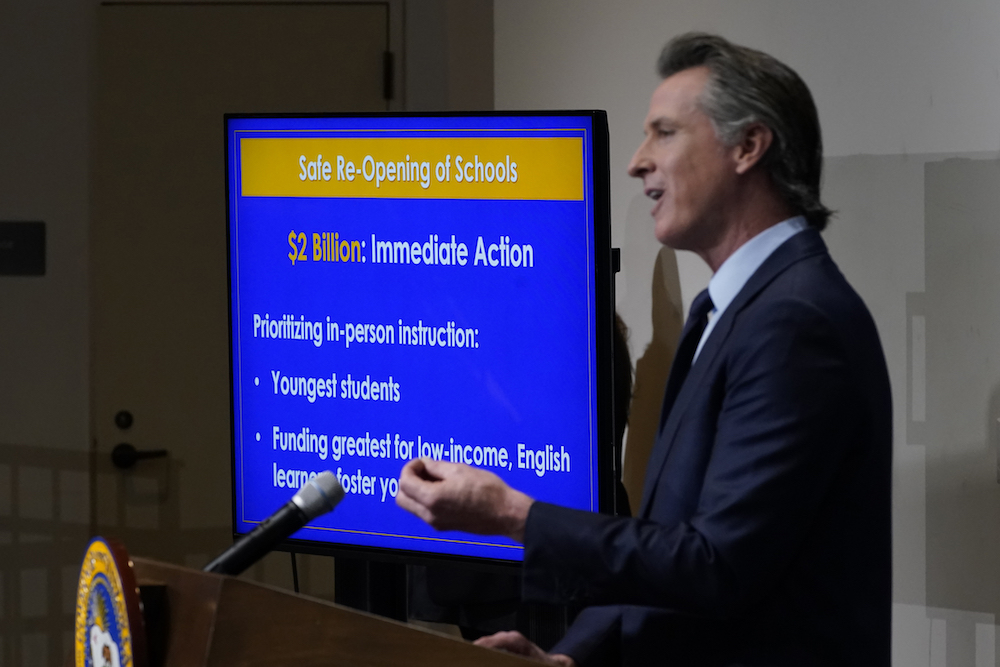

Gov. Gavin Newsom outlines his 2021-2022 state budget proposal. Courtesy of Rich Pedroncelli, Pool/Associated Press.

In the midst of California’s pandemic catastrophe, we may be seeing, at long last, the demise of the dominant mode of thinking of our state’s leaders: “budgetism.”

Budgetism is the false and conventional wisdom—promoted relentlessly by our state’s media and by elected officials of both parties—that the real measure of California’s success is the condition of the state budget.

For decades, if the budget was balanced or in surplus, California was supposedly on the move, a superpower, or even a national model of success. If the budget was in deficit, California was supposedly in crisis, a failed state, or a cautionary tale of excessive ambition.

But now the budget and everyday reality have diverged with tragic force. When Gov. Gavin Newsom earlier in January introduced a new budget with a $15 billion surplus, it occasioned little of the usual celebration and declarations of governance success. Instead, some wondered why the money hadn’t been already spent responding to the greatest emergency of many Californians’ lives.

The COVID-19 death toll is growing by hundreds per day, and has surpassed 30,000. Schools are closed at great cost to children’s development and mental health. Businesses have been shut, many forever, and thousands of people are abandoning the state altogether. Public fury is mounting against the pandemic response decisions of local and state officials, including Newsom, the target of a recall.

In the wake of this massive tragedy, we’ve managed to put aside our obsession with black and red ink, at least for now. But if this shift were to become a permanent thing, it would be a surprise—and a historic passing. That it has taken a once-in-a-century cataclysm to threaten our budget-centric thinking shows just how deeply ingrained budgetism has become in California, and just how divorced from reality our conversations about state governance have been.

Budgetism endured because it provided an easy, one-number scorecard to judge governance in a highly complicated state. Gov. Gray Davis might have reversed two decades of Republican dominance and achieved important education reforms, but he was a failure worthy of recall because he produced a massive budget deficit after the dot-com bust. Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger might have brought historic political reform and climate change legislation, but he was a failure because he presided over a big budget deficit after the Great Recession. (“Schwarzenegger legacy is crippled by budget deficit,” the Mercury News editorialized in a typical assessment.)

The Jedi master of California budgetism was Gov. Jerry Brown, who—despite neglecting mounting problems in everything from housing to unemployment insurance—left office as a media darling because he produced big budget surpluses. The Luke Skywalker of budgetism was the young and brilliant finance director and gubernatorial aide Ana Matosantos, a wizard at conjuring surpluses from California’s impenetrable budget rules.

But this particular force has a very dark side. Budgetism—by focusing so much attention on annual accounting—obscures deeper troubles.

Our state’s leaders like budgetism because it offers cover for their inaction and their failures to manage agencies, to reform the state’s many broken systems, and to execute the progressive policies voters say they want. Sure, major educational studies may conclude that California needs universal child care and more and better instruction for K-12 students, but that would require tens of billions in additional spending that could put the budget into deficit. Yes, the state’s faltering infrastructure, from waterways to health facilities, needs hundreds of billions of dollars in new investments, but we only can address a fraction of that need for risk of throwing the budget out of whack. And of course, it’s a matter of life and death that we accelerate management of our forests and wildlands to reduce fire risks, but can we really afford the cost?

Why hasn’t the dark side of budgeting been more aggressively and publicly challenged? Because politicians punish those who do. Democratic legislators who dare challenge legislative budgets and demand stronger investments lose committee assignments and offices, and get beaten up by interest groups and even their own party.

Over the past decade, when I’ve taken on budgetism in public forums, and suggested we need broader constitutional reform to produce better governing systems and management, I’m often dismissed by politicians and fellow pundits as “unrealistic.” (One Democratic consultant even dismissed me, a rather boring father of three living in a Southern California suburb, as “a revolutionary.”) And when I suggested in this space that then-Gov. Jerry Brown stop summing up the state’s prospects along budget lines and instead see more of California’s lived realities and broken systems in its different regions, he referred to me as a “declinist” in his state of the state address.

I pray that now, after this terrible year, politicians will stop the name-calling and the budgetism, and think more broadly about bigger changes in California, and broader measures to evaluate those changes. Good metrics would shift the focus from funding to management—a vital shift, in a state where bigger spending on homelessness hasn’t produced sufficient housing for the unhoused, and more money for unemployment hasn’t always reached the truly unemployed.

It shouldn’t be that hard to come up with broader measures of whether California is succeeding. So far, the most serious effort at quantifying that is the California Dream Index from the reform powerhouse California Forward.

The index tracks progress toward a more equitable California statewide and across 11 regions, on 10 indicators—air quality, short commutes, broadband access, early childhood education, college and career technical education, income above cost of living, affordable rent, homeownership, prosperous neighborhoods, and clean drinking water.

You can quibble with whether those are the 10 best indicators to follow, but the index offers the smartest measurement we have so far of whether California’s performance is meeting its people’s needs. And it’s a much more accurate picture of the state’s health than whether the budget is in balance.

Send A Letter To the Editors