The golden guns of the Museo del Enervante. Courtesy of Ioan Grillo.

Amid the gridlocked streets of northern Mexico City lies a fascinating and surreal museum that is not open to the public. Officially called the Museo del Enervante—a rather dull technical name that could be translated as the Museum of the Stupefacient—it is better known as the “Narco Museum.”

Located inside the sprawling complex of the Ministry of National Defense, the headquarters of the Mexican army, the museum gets its unofficial moniker because it displays the craziest artifacts that Mexican soldiers have nabbed from drug traffickers. Vials of marijuana, crystal meth, heroin, cocaine—even black cocaine—are on display alongside chunks of “trap cars”—vehicles, with secret compartments in their gas tanks and seats, which are used to drive narcotics into the United States.

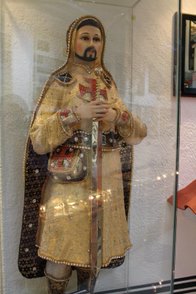

The highlight of it all is a room entitled “Narco Culture.” Inside are the glittering trinkets that traffickers spend their blood-stained dollars on—which means it’s where some of the billions of dollars that Americans pay for drugs end up. A cell phone is bathed in gold; a table and chair set are carved with symbols of the Santa Muerte, or Holy Death; a majestic lion and beautifully muscled tiger are stuffed and standing.

The “narco saint.” Courtesy of Ioan Grillo.

Journalists and investigators have to apply to the Mexican army to get into the museum. It would be seen as bad taste to open it to tourists while violence still rages. Since Mexico launched a military crackdown on drug cartels in 2006, there have been more than 300,000 homicides and tens of thousands of disappeared; soldiers and police themselves have carried out massacres.

Over two decades of covering the violence in Mexico, I have been to the museum three times for research, and I’ve watched the collection—which is displayed across several large rooms—expand with the addition of ever-weirder items.

For my most recent visit, I was focused on the weaponry because I came to research my recent book, Blood Gun Money: How America Arms Gangs and Cartels, which explores the iron river of guns flowing from the United States over the Rio Grande. But I was also interested in the culture around guns, and how the narcos decorate them like they are sacred items.

The guns in the narco museum include collections of full-sized rifles, especially Kalashnikovs, which the narcos affectionally call “cuernos de chivo” or “goats horns” because of their curved clips. These are mostly made in Eastern Europe, exported into the United States, sold retail, and then smuggled into Mexico. As a journalist, I have covered too many murder scenes where the bullets of AK’s and AR-15s are scattered on the street.

The narcos are also fond of handguns. In the museum, you see those that have been decorated and turned into high-priced collectibles or ornaments. Many have the initials of the drug lords spelled out with diamonds or other precious stones. One has JGL, short for Joaquin Guzman Loera, known to the world as El Chapo, who after many escapes was convicted in 2019 in New York and sentenced to life in the “Super Max” prison in Colorado.

Another handgun has an eagle under the letters ACF, the initials of Armado Carrillo Fuentes, nicknamed the Lord of the Skies because he flew cocaine in a fleet of private jets. Carrillo Fuentes is alleged to have died in a plastic surgery accident in 1997, while one of his old DC-6 planes has been turned into an attraction in a children’s play park in the town of Parral, Chihuahua.

Others bear the names of their owners’ heroes, such as Mexican revolutionaries Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa. And another pistol still has the name of Versace, citing the Italian fashion mogul and his label. It grabs my attention how drug lords can celebrate both revolutionaries and entrepreneurs. They are rebel capitalists.

Staring at the golden guns, alongside religious symbols such as the Holy Death in statuettes and paintings, makes me wonder why the narcos put their weapons on such a pedestal. Perhaps they venerate them as sources of power, the tools that have elevated them from poor campesino famers in mountain villages to millionaires or even billionaires in a booming global industry.

Yet the same guns drown their homeland in blood—and have been used to end the lives of many of these same gangsters and their loved ones. One gun in the narco museum is etched with that chilling quote attributed to Plato: “Only the dead have seen the end of the war.”

Mexico’s drug war has long been about more than drugs. The cartels have diversified into a portfolio of rackets, from stealing vast amounts of oil from pipelines, to wildcat mining that wrecks the environment, to seizing control of migration routes and extorting the undocumented people heading to the United States. The different sides of this war are blurred with top government officials accused of working for the cartels; among them, former Public Security Secretary Genaro Garcia Luna sits in a U.S. prison on drug trafficking charges.

While we might disagree about aspects of the drug wars, we should agree that they deserve commemoration. There has been a brutal period of violence here that needs to be remembered. Most of the sites of the worst atrocities have been left unmarked, as if nothing happened, when there could be plaques and memorials to them.

The Narco Museum is a tribute to this period. But it shows only one side of the story, one told by the army but showing the ornaments of the drug lords so it is glittering and golden. It doesn’t speak to the suffering.

I hope someday in the future, the museum can be opened up to the public with the golden guns alongside exhibits documenting the bloodshed and tragedy.

Such an opening will mean that the violence is history, a past story of conflict that can be studied, like the Mexican Revolution. If the flow of that iron river of guns could be slowed or stopped, then that day could come sooner.

Send A Letter To the Editors