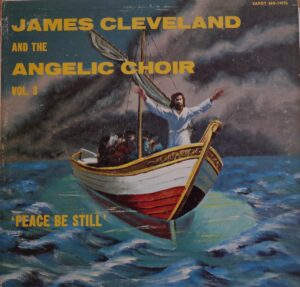

The Angelic Choir of the First Baptist Church of Nutley, N.J. recorded “Peace Be Still” under trying circumstances. Courtesy of Malaco Music Group.

“Peace Be Still,” a six-minute-long hymn, swept gospel radio in 1963.

Recorded just four days after the devastating bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, it became an instant classic, selling nearly a million copies to an overwhelmingly Black audience over the next decade.

Inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1999 and the National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress in 2004, “Peace Be Still”—the title track on a collaboration between the Angelic Choir of the First Baptist Church of Nutley, New Jersey, and the “King of Gospel,” James Cleveland—remains, to this day, an enduring cultural touchpoint for the ’60s. “No record ever,” wrote historian Anthony Heilbut, “neither Bing Crosby’s ‘White Christmas’ nor the Beatles’ ‘Abbey Road,’ has so blanketed its market.”

Of the thousands of gospel songs recorded in the early 1960s, how did “Peace Be Still” come to define its era? Was it a case of being the right song at the right moment? Were embers of emotion from the Birmingham blast hovering over the recording session that evening?

The cover of the album Peace Be Still, with artwork by Harvey Williams. The record’s title track defined an era of gospel music. Courtesy of Malaco Music Group.

That was my personal theory—that the song’s raw power was prompted by the terrorist attack. But when I interviewed Angelic Choir members, I discovered they saw things differently. They insisted that the bombing and other violent acts against African Americans did not govern their lives, nor their singing, that night. “We weren’t so disturbed that we couldn’t serve the Lord. We knew the Lord, and we were there to praise and lift up His name. That was the purpose,” one chorister, now in her 80s, told me. “So anything that happened anywhere else, we were just there to praise the Lord and thank Him that we were able to make it.”

Thank Him that we were able to make it. Therein lies the key to decoding “Peace Be Still”—gratitude to Jesus for helping his people overcome the winds and waves of oppression right there in Newark. In many ways, this sentiment speaks to gospel music writ large, which expresses the unflinching refusal of African Americans to surrender to life’s injustices, especially those incited by racial prejudice, and gratefulness to God for being their ultimate protector.

James Cleveland must have had this in mind when he recorded “Peace Be Still” in September 1963. By the time he began work on the record, the 31-year-old wunderkind from Chicago with a gravelly voice and a perfectionist streak had already amassed more than a decade’s worth of experience; a musician, singer, songwriter, and choir director, he’d done everything from steering Detroit’s Voices of Tabernacle to national acclaim for the album The Love of God to teaching a young Aretha Franklin to play piano.

His collaboration with the Angelic Choir came about thanks to a recording deal he signed with Savoy Records, an independent label with a rich gospel catalog, in 1960. The Rev. Lawrence Roberts, who was an executive at Savoy, also happened to be the pastor of First Baptist in Nutley and was responsible for organizing its choir, which sang in church every third Sunday in the early 1960s. When Cleveland approached Roberts to see if he would be open to letting him borrow the Angelic Choir for his recordings, Roberts agreed, but with one caveat: all sessions would have to take place in the church, where the choir members, who had little recording experience, would be more comfortable and their true essence could shine through.

Roberts’ stipulation proved wise: In 1962, Savoy and Cleveland recorded their first two albums with the Angelic Choir, captured during live, in-service recording sessions in the little wooden First Baptist Church. Both records, crackling with the spiritual electricity that arises between anointed gospel singers and excited congregants, exceeded expectations, won critical acclaim, and garnered big sales. The proceeds allowed the First Baptist Church to raze its wooden frame building and begin building a modern sanctuary.

Things had changed by the time Savoy authorized a third live volume in September 1963. Construction on the church still hadn’t wrapped, so the choir had to record in Trinity Temple Seventh-Day Adventist in Newark, where they were temporarily holding church services. Two key players from the original albums, Los Angeles choir director Thurston Frazier and organ prodigy (and future “fifth Beatle”) Billy Preston, were unable to make the September date. And the world was in turmoil. On August 28, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington, calling for civil rights and equal opportunity for Black Americans. Days later, on September 15, segregationists planted dynamite beneath the stairs of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church—killing four girls, injuring several others, and sending a devastating shockwave throughout the country. Places of worship had always been sanctuaries—literal and figurative—for Black people. Now even churches weren’t safe.

The Rev. James Cleveland was a gospel star before he worked on “Peace Be Still.” For decades after its release, he used the song to communicate his hopes for a better America. Courtesy of Malaco Music Group.

Nevertheless, the project proceeded. Cleveland, who had a reputation for deftly incorporating pop music techniques into gospel’s traditional core, selected “Peace Be Still” for the session after hearing a performance of Gwendolyn Cooper Lightner’s arrangement of the largely forgotten hymn in his newly adopted hometown of Los Angeles. Originally by Horatio Palmer and Mary Ann Baker, its lyrics were inspired by a New Testament story, chronicled in Mark 4:39. Jesus and his disciples were trapped on a boat during a storm: “And [Jesus] arose, and rebuked the wind, and said to the sea, ‘Peace, be still.’ And the wind ceased, and there was a great calm.”

For First Baptist, Cleveland added a few touches. At the moment in the lyric when Jesus commands the storm to stop, the Angelic Choir’s full-throated, staccato singing drops abruptly from fortissimo (thunderingly loud) to pianissimo (a whisper). The plunge elicits interjections of delight from the live audience and several choir members. They repeat the dramatic technique once again, to more shouts. The result is nothing short of spectacular sacred theater.

Perhaps lacking confidence in the album’s sales potential due to the absence of Frazier and Preston, Savoy created little fanfare around Peace Be Still’s release. The label pressed a standard 3,000 copies of the album, following a sales forecast that turned out to be off by orders of magnitude. “Peace Be Still” lit up phones at radio stations nationwide. By the end of the decade, it had sold somewhere between 600,000 and 800,000 copies, a phenomenal achievement at a time when gospel albums were lucky to hit 50,000 in sales.

“Peace Be Still” launched the Angelic Choir on the road. The group sang the hymn at the Apollo Theater and on television. They sang it at the New York World’s Fair. With Roberts as director, the Angelic Choir and James Cleveland recorded nine albums of live gospel music between 1962 and 1969, earning two Grammy nominations.

“Peace Be Still”’s impact transcends its musical drama. Like folk spirituals, it communicates on multiple layers. There is the miracle of Jesus saving his disciples by commanding the storm to cease. Then there is the allegorical statement: Because it was still risky for African Americans to record protest songs, the Angelic Choir employed the Bible story as allegory to express their hope, through faith in Jesus and personal resilience, for an end to the trials that came with being Black in America.

“Peace Be Still” is but one prominent example of how gospel music celebrates God’s dominion over earthly ills and how, in the form of a loving, fatherly Jesus, he protects and heals his people. The Ward Singers’ 1950 hit “Surely God is Able,” Rosie Wallace’s 1963 single “God Cares,” and “I Have a Friend Above All Others,” sung by artists from the Soul Stirrers to Sam Cooke and Al Green, make the same case. And no matter how bad life becomes in the here and now, gospel enthusiasts are reminded that a heavenly home awaits where, as songwriter Rev. W. Herbert Brewster wrote in the mid-1940s, the faithful will “be drinking that ol’ healing water; and we gonna live on forever.”

Like most Black music, “Peace Be Still” has evolved from coded message to explicit commentary. In 1976, the Heaven Dee-Etts of Trenton, New Jersey, covered the song as “All I Need is Peace.”

On it, lead vocalist Mary Glanton prays for relief from life’s trials: “Sometimes, sometimes, sometimes, Lord, my pillow gets wet with tears.” On her 1983 cover, gospel singer Vanessa Bell Armstrong transforms the song into a daily devotional, calling for peace “in your home, on your job, late in the midnight hour” and “when you don’t know which way to turn.”

By the 1980s, James Cleveland was using “Peace Be Still” to communicate his hopes for improving race relations in America, even in the face of injustice; just a month after Cleveland’s death in February 1991, three Los Angeles police officers beat Rodney King after a high-speed chase. Their acquittal in April 1992 sparked five days of civil unrest in Los Angeles.

Leading up to the song’s dramatic climax is the disciples’ final desperate plea for Jesus to rescue them from destruction: “The winds and the waves shall obey thy will.” The danger of the wind and the waves represents different things, to different people, at different times. For some, it represents hunger or poverty, for others it is mental or physical anguish, and for others it is violence or discrimination. But listening to it today, “Peace Be Still” can still calm the soul whenever and wherever the storms of life are raging. Its performance evokes both a nostalgic yearning for the timeless lessons taught in the little wooden churches of yesterday and hope for a better tomorrow.

“I think ‘Peace Be Still’ has lasted all these years,” remarked the Reverend Dr. Stefanie Minatee, whose mother Pearl sang on the record, “because people are living in turbulent times and they are looking for something to hold onto.” Jacqui Watts-Greadington, a latter-day member of the Angelic Choir whose aunt, Bernadine Hankerson, sang with the choir in 1963, agrees. “I often say that when trouble comes, you think about songs like ‘Peace Be Still.’ Those are the songs that carry you through.”

Send A Letter To the Editors