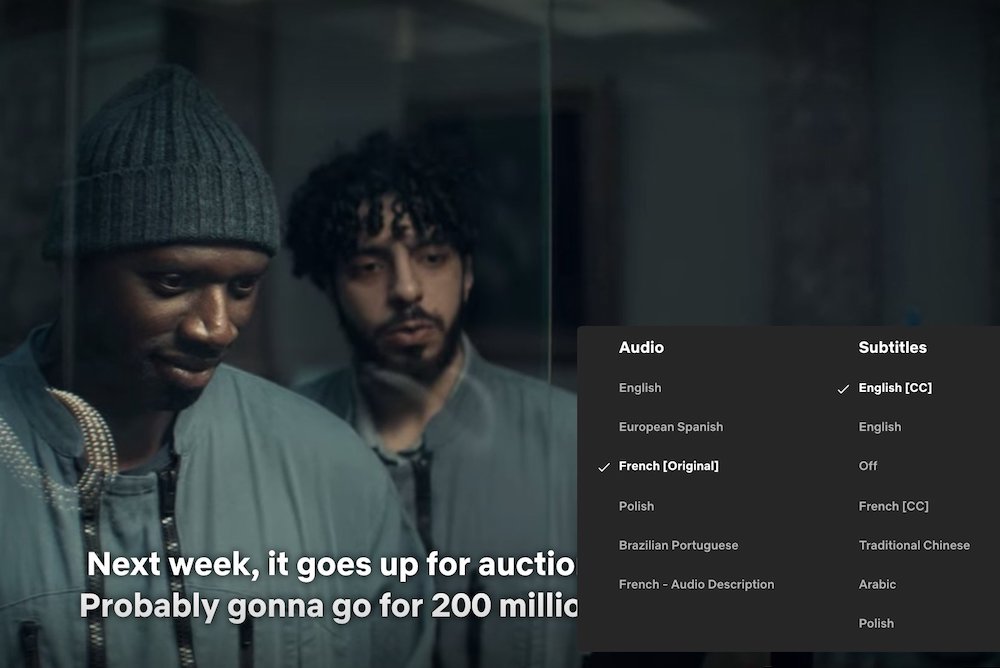

The French mystery thriller Lupin became the most-watched non-English series on Netflix and is also the platform’s most popular series of 2021; it’s been lauded for its seamless translations. Courtesy of Netflix/Lupin.

If you don’t notice my work, it means I’m doing my job properly.

I’m an audiovisual translator, which means that I—and others like me—help you understand the languages spoken on screen: You just click that little speech bubble icon in the bottom-right corner of your preferred streaming service, select the subtitles or the dub, and away you go. These scripts are all written by someone like myself, sitting quietly at a computer and spending day after day trying to figure out, “What are they actually saying here?”

I decided to become an audiovisual translator because it allows me to combine cinema and French culture, my two favorite things. But there is also something about the anonymity of the work that appeals to me, which is the name of the game for our craft. As Bruce Goldstein, director of repertory programming at New York’s Film Forum, put it in The Art of Subtitling, “Good subtitles are designed to be inconspicuous, almost invisible.”

Of course, it’s impossible to be truly invisible. Translating film and TV always involves some form of compromise. But we do our best, carefully dissecting what is being said in the source language, then reassembling it in the target language so that you have the same viewing experience as a native speaker, and may even forget you’re watching a “foreign” film. Whether working (as I do) from French into English, from Spanish into German, or Japanese into Swedish, the process is always the same: We pay close attention not only to the meaning of the words, but to the actors’ emotions, the cadence of their speech, their body language, the themes and narrative structure of the script, the historical period, and the social context. Together, these cues provide a host of tiny hints, all of which add extra layers of meaning and must be accounted for in the translation. Translating all these layers is a bit like solving a Rubik’s Cube—it’s easy to do one side, but what about all of the others?

Say I’m dubbing a ghost story set in a bourgeois Parisian household in the year 1850. The French grandmother stands in a doorway and whispers, “A tout de suite, mon petit.” How would you dub that into English? I might try, “See you in a minute, my darling,” but that doesn’t sound stuffy enough for the 19th-century bourgeoisie. It needs to be more uptight, more formal. So what about, “See you in a moment?” The issue there is the cinematographer has lit the scene so the actor casts a sinister shadow into the room. She’s not just standing there, she’s lurking, and if I were a grandmother trying to lurk in a doorway, I wouldn’t say, “See you in a moment.” However, I might say “See you soon.” That could work—especially when you consider the spooky quality about the alliterative s’s and the ghostly “ooh” in “soon.” “See you soon, my darling” perfectly fits the atmosphere of the scene. Except this introduces a new dilemma: “my darling” doesn’t sync with the actor’s lip movements. Her mouth is closed for the “p” in “petit,” whereas the “d” in “darling” would require it to be open. In dubbing, the end of a sentence is one of the most important parts to get right: If the last word is poorly lip-synced, it sticks out like a sore thumb and risks distracting the viewer. In an ideal world, I’d find a new term of endearment that syncs with “mon petit.” “My petal,” perhaps, though it is not nearly as good as “darling”—it makes the grandmother sound too affectionate. But in this case, a compromise is necessary. At the end of the day, a loose translation is less distracting than bad lip sync.

At times, I also must compromise when it comes to personal taste. For example, I might be subtitling a rapper renowned for Eminem-style punchlines, like: “C’est le retour de la légende de Jimmy, même si j’peux craquer à tout moment comme Djibril.” With these lyrics, they’re making a tasteless joke, comparing themselves to Djibril Cissé, a French footballer who has broken both of his legs. I don’t find broken legs especially funny, nor is it a joke that I would ever make myself. Still, this sick humor is a key element of their controversial persona, and the English-speaking audience deserves to understand what they’re saying so they can make up their own minds. A translator must never censor the source material: I must put my own opinion to one side and render the translation as faithfully as possible. It’s a challenging task, but also an instructive one.

In this case, since most Americans are unlikely to have heard of Cissé, I start by “translating” his name into that of another famous sportsman, a popular figure that an American audience would recognize by name. In order for the punchline to work, I need someone who would have suffered some kind of terrible injury. A fairly gruesome Googling session suggests the late basketball player Kobe Bryant, who died in a helicopter crash. Now I need to reverse-engineer the scenario. At first, the rapper pretends to be arrogant (légende), then undercuts themself by admitting they’re scared of failure (craquer… comme Djibril). After looking for an arrogant-sounding phrase that rhymes with “Bryant”—eventually settling on “rap giant”—I must find a way to describe Bryant’s accident that also acts as a metaphor for failure. This produces the solution: “It’s the return of the rap giant, even if I might crash any minute like Kobe Bryant.” The offensive punchline leaves a bad taste in my mouth, but because it leaves the same bad taste as the original French, it feels like a faithful translation.

My job is always easier when I’m working on a story that I really care about. If I’m hooked by the plot and can empathize with the characters, then I can produce a deeper, more intuitive translation because in that moment, I am that character. When my wife gets home from work and asks how my day went, my first impulse is not to tell her about myself, but about the imaginary colleagues on my computer screen. I spend my days listening, empathizing, and listening some more, until eventually I lose myself in whatever I’m translating, and become invisible. When the process is flowing well, it’s both relaxing and satisfying, like being in a meditative state in which I’m channeling the emotion of every scene. There have even been a few times over the years, when I’ve been working on something especially good, that I was so immersed in the story that translating a single line of dialogue left me breathless or moved to tears. It can be quite jarring to reach the end of the working day and suddenly have to emerge from this fictional world, to open my mouth and speak my mind again, to remember who I am.

This line of work is not really suited for those with big egos. Most of my colleagues—the actual, real-life ones—are modest, sincere, and soft spoken. And even though these qualities are the very things that make us good at our job, I do wish that we could sing our own praises a little louder, and bring some more attention to our invisible craft.

Especially because these days, though there are more films and TV from around the world than ever before, in many countries (such as the UK, where I live, or Spain, where my colleagues assure me the situation is even tougher), rates are falling and deadlines are getting tighter. This has inevitable repercussions on quality, not to mention our livelihoods. It can be hard to publicize our achievements because we usually sign non-disclosure agreements, and more often than not, filmmakers regard us as an afterthought, something to be rushed through at the distribution stage. Thankfully, many of the best filmmakers realize how important the translation stage is and are closely involved in the subtitling and dubbing process. They also pay fairly, so that we can take our time getting it just right.

It’s possible for subtitles and dubs to be so seamless that they feel invisible without pushing audiovisual translators ourselves out of sight. I’m proud of what I do, and I want the world to know how much care and consideration I, and thousands like me, put into our work. That being said, there is still a certain satisfaction in being the hidden conduit between cultures, the solitary name that appears in a film’s credits after everyone has left the cinema. It is precisely our invisibility that allows a family watching Netflix in Chicago to empathize with a bourgeois grandmother in Paris or an edgy rapper in Caen. Translation is about helping people to understand each other, and it feels good to be able to do that on a daily basis.

So the next time you click on that intriguing Polish dystopian thriller, or the latest award-winning Italian gangster series, spare the briefest of thoughts for all the people behind that little icon in the bottom-right corner. Then please, forget all about us.

Send A Letter To the Editors