Illustration by Be Boggs.

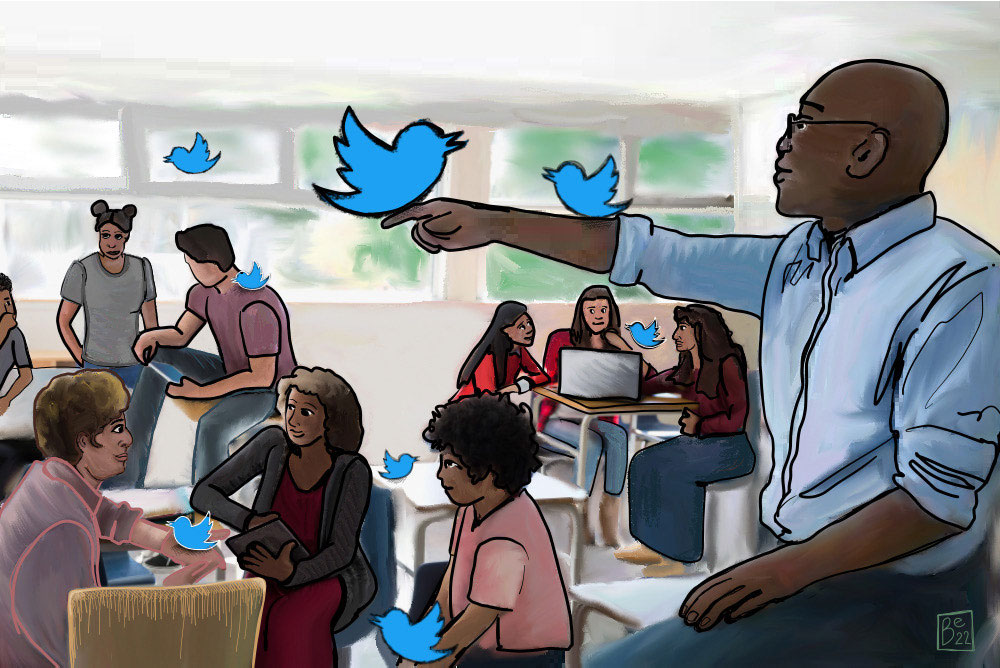

For most teachers, social media has no place in a classroom. When they do use it, they often retreat to or remain within the safer confines of “walled garden” discussion and message boards where everything can be monitored and tracked and kept isolated from the outside world. But since 2015, we’ve been training our Advanced Placement U.S. History students at Barrington High School, in Illinois, to step into the “Wild West” of the real internet.

As social studies teachers, our job is to help build informed, concerned citizens who participate in our society. In turn, we strive to cultivate and model appropriate behavior. For decades that only entailed the physical world, but times have changed. According to a 2018 study of teen social media habits, 95 percent of students have a smartphone, and 45 percent are online “almost constantly.” As teachers, we can choose to ignore social media because of its negative attributes or we can acknowledge that our students are using it and take responsibility to help them form healthy, intelligent, appropriate habits on it.

Incorporating social media into our lesson plans was something that began organically. Back in 2013, our district, Barrington 220, rolled out a 1:1 program to provide all students with a laptop or tablet to support their learning. In keeping with this initiative, we started sharing additional materials and articles on Twitter that supplemented our course content for interested students. Eventually, some industrious ones began to share and create content of their own, which, over time, led to a “back channel” discussion emerging on Twitter. We found that the students who were accessing and contributing to it on a regular basis were more tuned into our course and tended to perform better on assessments. When some of the quietest students in class found their voices via Twitter, too, we became convinced that we were really onto something; not only were we now often hearing from students we would not have heard from otherwise online, these more hesitant students were becoming comfortable enough to contribute more in class as well.

Once we decided this back channel was a useful aspect of our course, we began to create a more formal pedagogy around it, giving students the option to participate in class discussions in person or via Twitter by tweeting to the course hashtag #APUSH220 from a school-related Twitter account. The need to explicitly teach various elements of digital citizenship arose out of necessity from there.

Because we require students to tweet @ their source as a citation, and we encourage them to find and tweet @ the author, too, they become part of real-time conversations. Students’ tweets will occasionally bring journalists and historians into brief discussions with us—sometimes to answer a question or clarify a point, or sometimes simply to thank them for reading and sharing. Our students are always delighted to have the academic world acknowledge the work they’re doing, and we always appreciate professors and writers taking time to interact with our students.

Still, if you’ve spent any time online, you won’t be surprised to learn that such interactions don’t always go smoothly. Anonymous accounts have argued with, instigated, and mocked our students. We have had our own students bombard the hashtag with inappropriate material, sometimes intentionally, sometimes not. A few students have shared inflammatory opinions about current politics or other unrelated events. But when a troll or some other anonymous malcontent tries to mix it up with our students, it provides for an excellent teachable moment. We discuss, as a class, how to handle it and what course of action to take using the “reporting” and “blocking” features. We have even taken these steps together, as a class in order to address issues. In relevant instances, we begin by speaking to the individuals involved, whether they are the victim or the perpetrator, in order to remind them of appropriate behavior and the right steps. It’s the 21st century equivalent of “how to handle a bully.” This training is especially important because, according to Pew Research, 59 percent of teens today have experienced cyberbullying or some other form of online harassment. By offering guided experience in these situations, we can empower students to know what to do and to see that they should expect, and demand, to hold each other more accountable for their actions.

Of course, to be a responsible digital citizen today also requires the skill to differentiate valid, reliable sources from those that are not credible. But determining the reliability of online sources is not something that the average high school student is trained to do. A 2016 study led by Stanford History Education Group’s Joel Breakstone and Sam Wineburg confirmed our own observations: students are painfully bad at determining a reliable source from a piece of propaganda, misinformation, or “fake news.” As our students naturally make mistakes with what they are sharing and saying, each misguided tweet becomes a real-life teachable moment. Additionally, each positive contribution became a real-life example of good digital citizenship and a chance to further applaud their growth.

In that vein, we also encourage students to use our school-affiliated Twitter accounts to share their own creativity with a wider audience. Student musicians have shared videos of themselves performing music from our period of study. Our student artists have shared a wide variety of art related to the content, from political cartoons, to comics, to beautiful pieces packed with symbolism. We even invite and encourage our students to create their own memes about course content. All of these creative expressions are seen by people outside the walls of our classrooms, which improve the quality of our students’ work because they took this “authentic audience” into consideration when creating their pieces.

There’s another benefit to this type of teaching: the pace of an AP U.S. History course is fast and no single topic is lingered upon for very long. The constant back channel discussion on Twitter allows for our students to discuss any topic they want in greater depth or detail. Additionally, students can bring information into the course that would otherwise be missing. If a student wants to opine about the quality of the front-facing armor on a WWII Sherman tank, they most certainly can (as long as they cite their reliable sources). Stories about our students’ families, or the sharing of artifacts or heirlooms, can also be done, quickly and easily, on Twitter. Students who ask niche questions in class that require further investigation are encouraged to do so and to share their findings for the benefit of all of our classes. Any group, point of view, or intricacy of history is encouraged as long as it constructively adds to our class discussion.

As to be expected, the quality and frequency of the discussions on our course hashtag ebbs and flows from class to class, based on the personalities of the students. But all it takes is a few bold students to “jump in” and get the conversation going, and then many other students more comfortable on the periphery are willing to contribute. The better the students know each other in person, we have found, the more likely they are to put themselves out there on Twitter. We know to expect that each year’s discussion will look nothing like the previous, with our different students, with different interests and personalities, but that is simply the result of allowing students to choose and control the direction of their own online conversation.

Though we keep participation on Twitter optional as to remain respectful of rules and expectations students may have at home, we’re fortunate to have had the overwhelming support of parents, guardians, and administrators over the years toward our work. In 2018, our district even brought in Devorah Heitner, a scholar on digital media and technology, to speak on the importance of strengthening digital citizenship through the cultivation of positive online relationships, reputation, and time management skills.

We strongly believe that the only way the narrative around our nation’s use of social media will improve is if we choose to take on this challenge and show students how to be good digital citizens. We’re proud to have created our own little carved-out corner of the real online world, where we can encourage students to take risks, make mistakes, learn from them, and improve. In turn, we hope that #APUSH220 elevates our students’ training to something integral, not just to the course but to their lives.

Send A Letter To the Editors