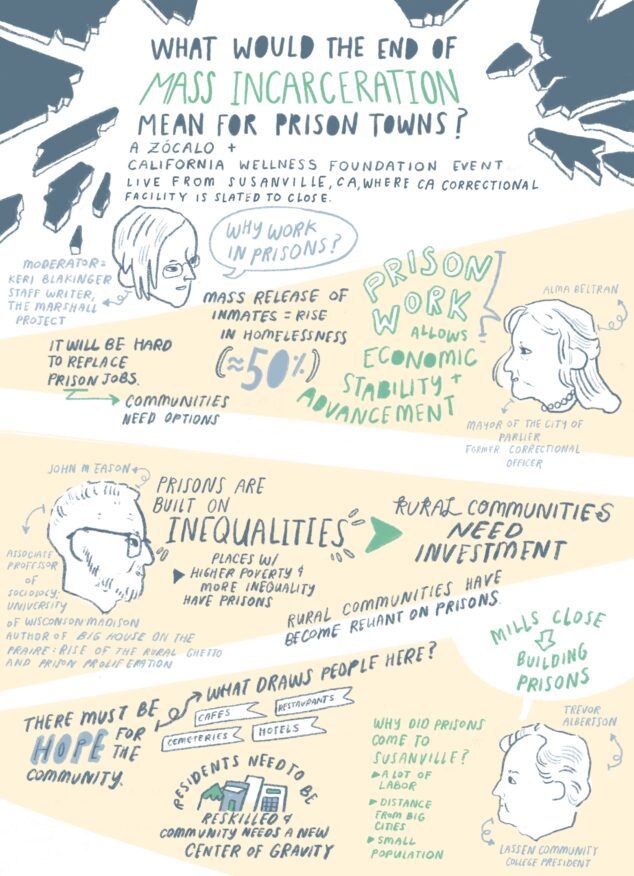

From left to right: Keri Blakinger, Alma Beltran, John M. Eason, and Trevor Albertson.

Efforts to close prisons need to come with assistance to rural communities that depend on these institutions, said panelists at a Zócalo/California Wellness Foundation event in the northeast California town that could see a prison close this year.

The event—titled “What Would the End of Mass Incarceration Mean for Prison Towns?”, which also was accompanied by a collection of essays on the subject—was held at Veterans Memorial Building, on Main Street in Susanville, California. Susanville has a population of 16,000, nearly 7,000 of whom live in its two prisons. The state of California has announced its intention to deactivate the older of the prisons, California Correctional Center, by June 30, 2022; the city has brought a lawsuit to stop CCC’s closure.

The panel—which brought together a leading scholar of prison towns, a former correctional officer and current mayor of another small California town, and the president of Susanville’s local community college—linked Susanville’s current predicament with national debates about criminal justice. In different ways, the panelists made the case that the challenges of ending mass incarceration are linked to America’s failure to invest in and develop its rural communities.

“There are opportunities in rural America,” said University of Wisconsin sociologist John M. Eason, author of Big House on the Prairie: Rise of the Rural Ghetto and Prison Proliferation. “And we haven’t focused enough on giving rural communities enough attention to wean themselves off of caging people.”

The event was moderated by Marshall Project staff writer Keri Blakinger, who noted that she herself had served time in prison. She pressed the panelists on why towns become dependent on prisons, and how they might take a different economic or civic path in the future.

Eason, who also directs his university’s Justice Lab, said that while there is considerable attention on the inequality prisons create, we often overlook that prisons were built on inequality. Rural communities with high poverty rates are more likely to have prisons. At several points, he noted that the late-20th-century boom in prison construction has often been the country’s only public works program for rural places.

Eason detailed how he has mapped and created data sets on all state-owned prisons built in the United States—more than 1,600—and analyzed the towns where they are located. When you compare towns with prisons to similar towns without prisons, the prison towns see a rise in median home value and median income, and decreases in unemployment.

But that isn’t the whole story: “Rural communities are sending more people to prison than ever,” he added.

Eason called Susanville an “outlier” among prison towns for various reasons, including being whiter and more Republican than many such communities, and having unusual infrastructure strengths. But he also noted that Susanville was representative of communities that became dependent on prisons after losing major industries.

Historically, Susanville attracted a young male labor force to work in timber, mills, and farming, another panelist, Lassen Community College President Trevor Albertson, explained. But when the first prison, CCC, came in the 1960s, he said, the prison paid more than in the mills, which began to close. With the arrival of the second prison 20 years ago, prisons became dominant economically, at some cost to the town’s commercial vibrancy.

Albertson said that the state’s announcement of its intent to close CCC, and the litigation to stop the closure, had created uncertainty for the town and for prisoners. His community college, whose student body includes inmates, could lose about 200 full-time enrollments. They’ve been working to make sure that their students continue to receive education, whether they stay or are moved to other facilities.

Image by Soobin Kim.

“Where it has been troubling and really problematic with the closure … is the not knowing. I know it wears on folks in town, I know it wears on folks working inside the prison,” said Albertson. The inmates are not immune, either. “No one asks about the folks in that prison.” Those students’ concerns are particularly troubling, he added, because “when you can’t control your own life, how can you control your education?”

Another panelist, retired correctional officer Alma Beltran, is the mayor of Parlier, a city of more than 14,000 people in Fresno County. She spoke extensively about Avenal State Prison, where she said she took a job because of the good pay, job security, and opportunity for advancement.

She also detailed how the town of Avenal depended economically on the prison. Prison employees and sub-contractors drove home buying, apartment rentals, and retail sales. And the spike in Avenal’s population numbers, as a result of the growing numbers of inmates, made the city eligible for more federal and state funds based on population.

In response to questions offered in the YouTube chat room or by text, panelists addressed Susanville residents and their current predicament directly.

“You are very important because you are the first rural institution to close,” Beltran said of the CCC prison. But she added, it won’t be the last—she anticipated seeing Avenal on an upcoming list of closures. “Other cities need to look at what’s happening here, because they might be next.”

Albertson, the community college president, said that “there’s something next” for Susanville. There is economic development money to “reskill” people who need new jobs as well as the possibility of creating a new “center of gravity” that would draw people to the region.

He offered an idea for one such entity: Susanville’s beauty and location make it a strong candidate to be the home of a new national cemetery, which could draw visitors and help the local economy.

“There has to be something beautiful after there has been something ugly,” he said.

Eason, in addressing Susanville, said that many urban people don’t care about rural places, so Susanville has to do the work itself.

“My question is: what’s the local infrastructure that is compatible with growth industries?” Eason asked. “How much investment would it take? This isn’t something you snap your fingers or change overnight.”

Susanville needs a plan, and he offered personally to assist the town in putting one together—because its future is crucial for rural communities everywhere. “If you want to close prisons,” he said, “you have to give rural communities some options.”

Send A Letter To the Editors