When Kids Make Art, a Richer Story of War Emerges

The Stone Soup Refugee Project Helps Young People Move Beyond Empathy

The sea is stormy, please help me!

My wings are small, please help me!

The butterflies are afraid, please help me!

My world is ignored, please help me!

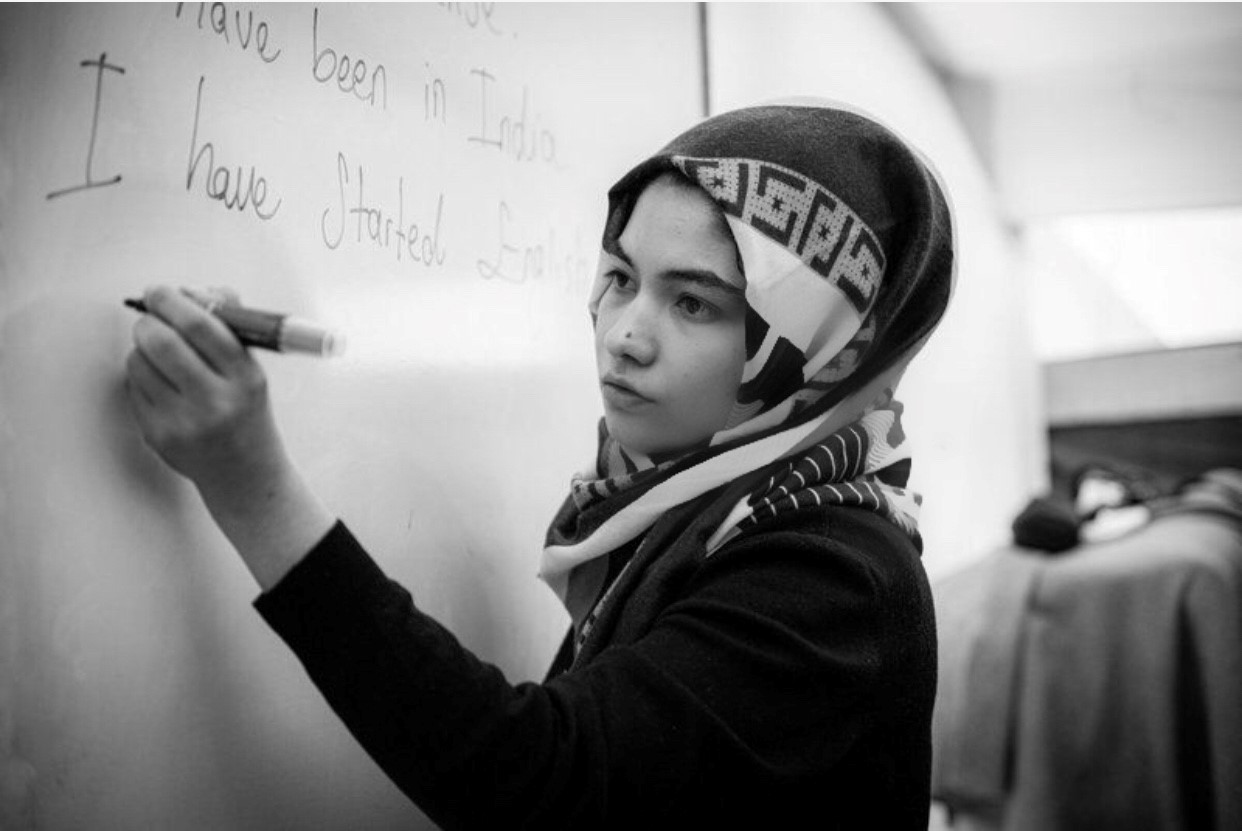

Parwana Amiri, a poet from Herat Province, Afghanistan, was 16 years old and living in Ritsona, a refugee camp north of Athens, Greece, when she wrote these words. Her poem “Fly With Me” challenges us to look and beckons us to listen. We do. And we feel her desperation, her hope, her anger. But we also anticipate this narrative. Her words fulfill and breathe life into our expectations of the experiences of a teenager displaced by war. But what happens when we move beyond passively receiving a work like this? What happens when young people, in particular, consider these works with more context—about the artists, their life histories, and even the more mundane aspects of their everyday lives?

Getting past the immediate expression of knee-jerk empathy—as human as that feeling may be—and creating an experience of deep reflection rooted in knowledge and personal connection is a core operating principle of the Stone Soup Refugee Project, which I direct. In collaboration with organizations around the world, we publish young refugee artists in Stone Soup, a literary magazine by and for children, facilitate creative writing workshops, and connect young people living in refugee camps to those living outside of such precarious situations as artists and writers. Through sharing creative works produced under starkly different circumstances, the young people gain dimension and nuance to one another, and move beyond dominant narratives of war and suffering.

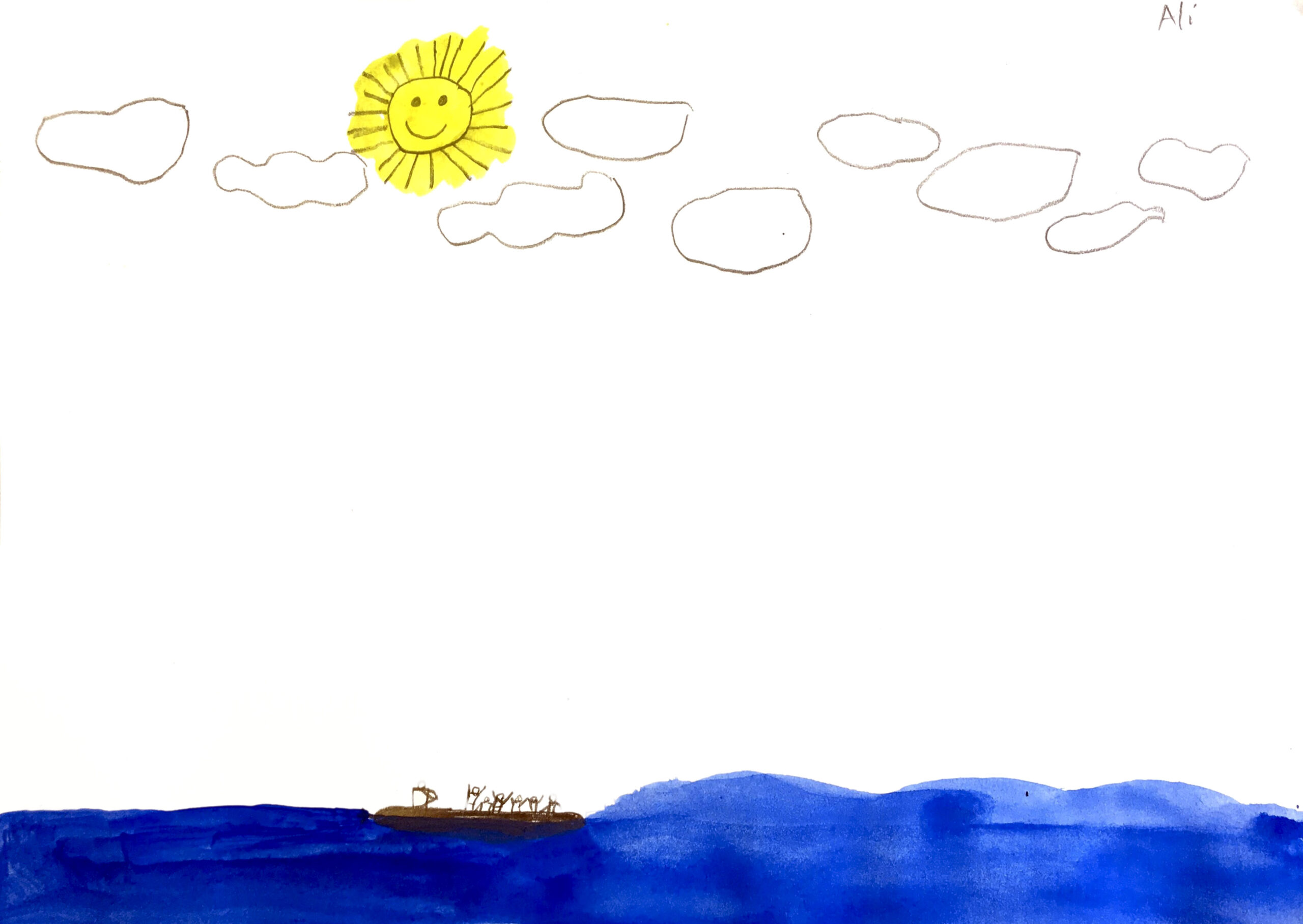

Young people, like most of us, approach the art and writing of young refugees from a place of empathy. When we see the tear-streaked face of a father cradling the smiling head of a dismembered body, limbs strewn about while bombs drop debris overhead, in a drawing by a 13-year-old Syrian girl, we feel empathy. When we see 12-year-old Ali’s painting of a lone boat floating beneath a smiling sun on an otherwise empty, rolling sea, its passengers’ stick-figure arms outstretched in desperation, we feel empathy.

Indeed, Jack*, a British participant in our pen pal program, expressed this sentiment in his correspondence with Sammah, a young refugee in Kenya. “I know that you have a hard life. You must be so brave to survive,” Jack wrote. “I can’t believe that you have an alien identity. I live in a solid house, with a passport. I wouldn’t survive in your condition.”

Sammah responded with a picture of her coffee grinder and explained, “We’re Ethiopian, we like coffee.” Alongside a picture of her house, she wrote, “This is what the houses here look like.” Her letter closed with an echo of Jack’s sentiments. “I will not give up” sits wedged between a drawing of a tree and her thatched roof house. Amid the vivid imagery and enthusiastic descriptions of the material objects that comprise her daily life, these words feel like an afterthought.

Through personal contact, a different, richer story emerges between young people. A story grounded in context wherein school work, friendship, and family life emerge with deeper significance against the backdrop of a starker reality of which Jack was already, perhaps vaguely, aware. Through these kinds of exchanges, young writers and artists, like Jack and Sammah, become people to each other.

Another project, the “Half-Baked Art Exchange,” a joint initiative of the Stone Soup Refugee Project and U.K.-based My Start project, allowed South Sudanese boys living in Kakuma Refugee Camp to create a piece of artwork in collaboration with young members of the broader Stone Soup community based in the U.S. and the U.K.

We began with a workshop where Kakuma Camp participants created an original piece of artwork, reflective of their lives, with a My Start project facilitator. Meanwhile, Stone Soup participants attended a workshop to learn about life in Kakuma Camp and various aspects of their partners’ cultural practices and lived environments. Following this, Stone Soup participants received the works created in Kakuma Camp and added to them in ways that sought to highlight the original piece while creating a dialogue between two people and two worlds.

Akech, from Kakuma Camp, began “Silver Specks” by layering found objects, colored packing paper, and thick glue baked in the desert sun to depict a line of yellow, green, and red squares with scattered flecks of silver against a brown background. His U.S.-based partner, Georgia, interpreted the colored squares in “Silver Specks” as a road, and added shadowed silhouettes, and little bits of sticks tied with wire to represent a fence. “I wanted to show joy, bright and bold,” she said, “but still trapped in the brown land, caught by the sharp threads of a barbed wire fence.”

For participants like Georgia, the workshop offered an opportunity to humanize and gain a deeper understanding of the experiences of young people displaced by war, social collapse, and climate crisis. As part of their workshop about life in Kakuma Camp, Georgia and her fellow Stone Soup participants had viewed a video showcasing the lives of Akech and other Sudanese artists. “Most people imagine [a refugee camp] to be a toxic wasteland full of sadness and hunger and a weary thirst for escape,” Georgia explained. But the video “showed people dancing, laughing, hugging, and going about their daily lives.”

For the young refugee participants, this workshop, and other Stone Soup initiatives, offer a platform to tell their own stories, in their own voices, for an audience of their peers. Lobola, a Sudanese boy, said his piece, “Full Pink Sun Half a Yellow Sun,” depicted how being in the camp “is like being in another world [apart] from the rest of the world and the sun is in the middle because it is so so hot here.” His collaborative U.S.-based partner, Anika, added a piece of paper with the word “Home”—because it is not just a place of abstract suffering, but a home, and for many, including Lobola, the only one he’s ever known.

This storytelling has powerful effects. Parwana Amiri, the 16-year-old writer of “Fly With Me,” says that for her, “writing is immortality.” By immortalizing a young person’s experience of war and trauma, and providing a deeper connection and context for their art, we move beyond the simplistic initial response of empathy that war narratives provoke. And in forging deeper solidarities, our own sense of agency comes into being—a sense of agency from which we might disrupt hollow deflections of suffering in favor of imagining alternative possibilities.

Send A Letter To the Editors