Finding L.A. in Food Splatters and Spiral Bindings

Three Centuries of Cookbooks from Clubs, Churches, and Other Groups Chronicle How the City Has Lived, Worked, and Eaten

This piece publishes alongside the Zócalo/LA Cocina de Gloria Molina/California Humanities program “Do We Need More Food Fights?” tomorrow, Thursday, September 14, at 7PM PDT. Register to attend online.

When I open an old cookbook, one of the first things I look for is a “splash page”—one covered with decades of food splatter. It’s a strong indication that the recipe on that page is a good one, well-loved, and often used. Drops of red sauce on yellowing paper become marginalia, a notation from readers past, and a way to commune with previous generations in the kitchen.

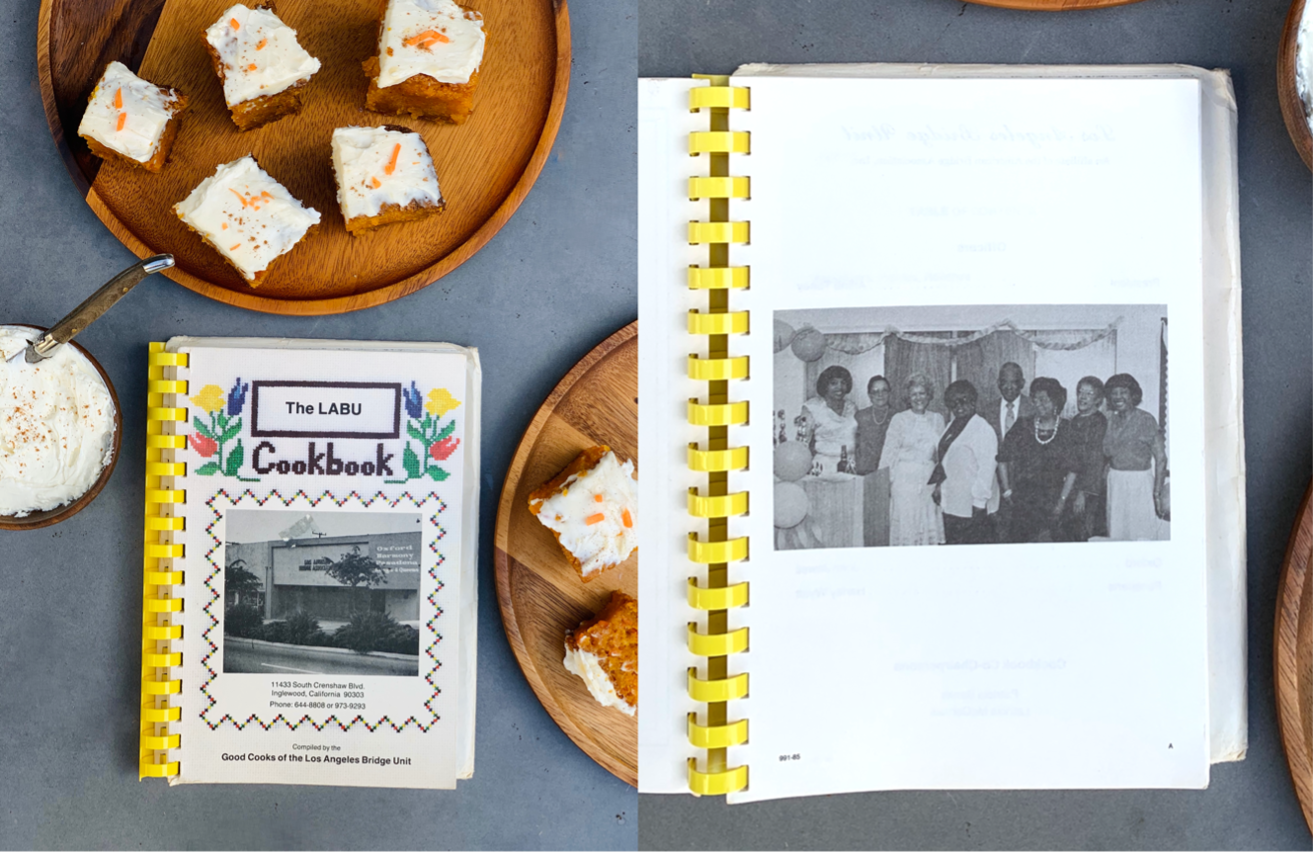

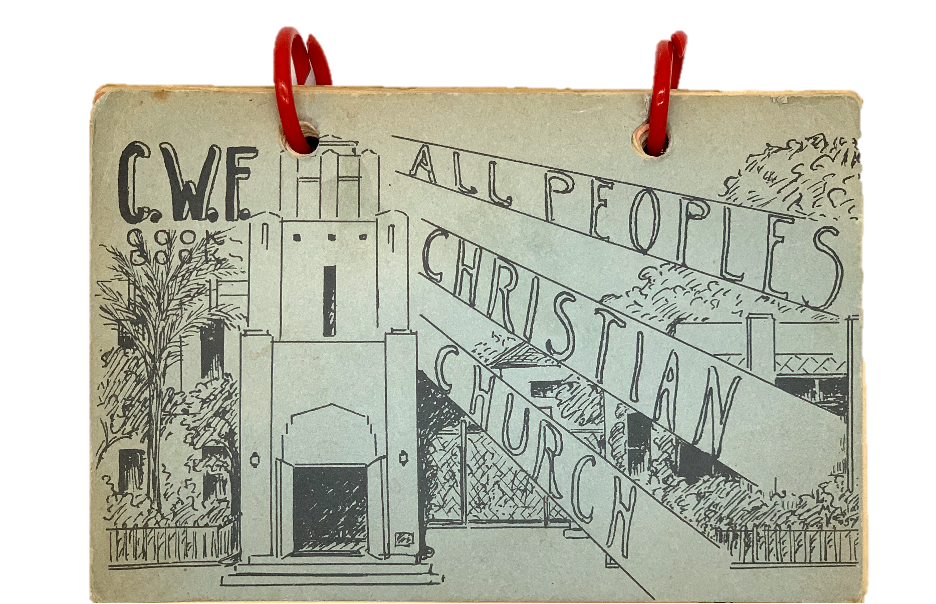

Several years ago, I began collecting and cooking from community cookbooks I found in the bottom of boxes in thrift stores and at estate sales around Los Angeles. At first it was the covers, not the recipes, that caught my eye. Like the hand-drawn rendering on the front of a 1950s cookbook from All People’s Christian Church in South Central. But soon, I was cooking from the books weekly, often Googling the recipe contributors to try to learn more about them. In California Cooking, recipes compiled by the Art Museum Council of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1986, I found the name of a dear friend’s recently deceased grandmother—a happy surprise.

I started digitizing these books, and my personal collection grew into the Community Cookbook Archive: LA, which now houses over 400 recipe books from Los Angeles clubs, collectives, and organizations. These self-published books weren’t from famous chefs or instructors but instead shared how non-professionals cooked at home. While many of them are not in libraries or other institutional holdings, they were preserved on home bookshelves, passed between generations, and now serve as amazing records of Los Angeles culture.

The term “community cookbook” conjures images of volumes spiral-bound in the 1970s, filled with instructions for Jell-O molds and tuna casseroles. But collective recipe books are a far older phenomenon, dating back long before coil binding was even invented. The books in the Community Cookbook Archive span three centuries of Los Angeles. Indeed, as soon as there was hardcover book printing in this city, there were community cookbooks. Early community cookbooks were typically sold as a creative fundraising tool for women’s clubs and church auxiliaries who did not have access to more traditional modes of funding. However, by the mid-20th century, all sorts of groups were compiling recipes—a bridge club in Inglewood, a bowling league in Long Beach, docents at the Natural History Museum, and the Universal City cast and crew of the TV show Murder She Wrote.

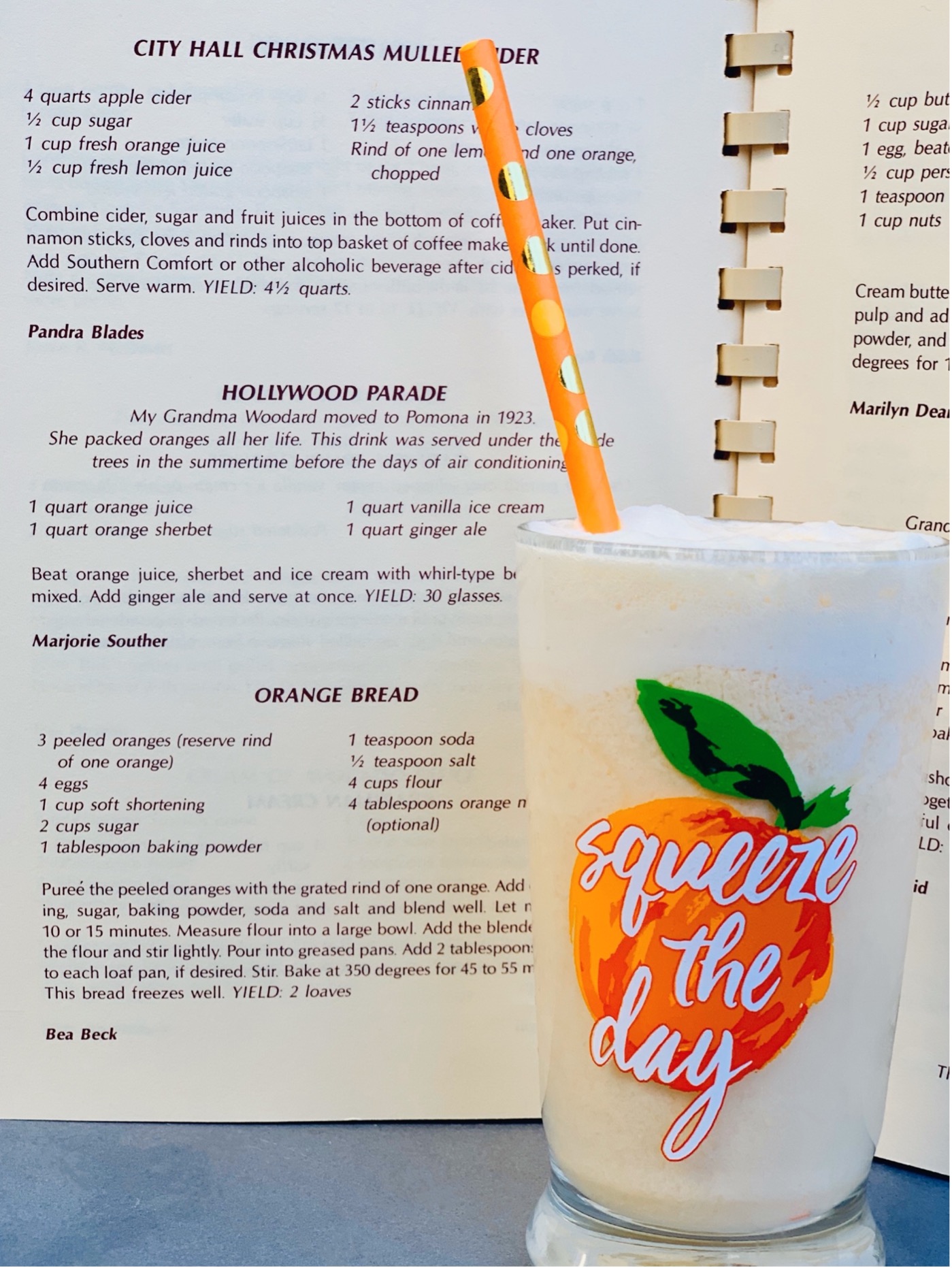

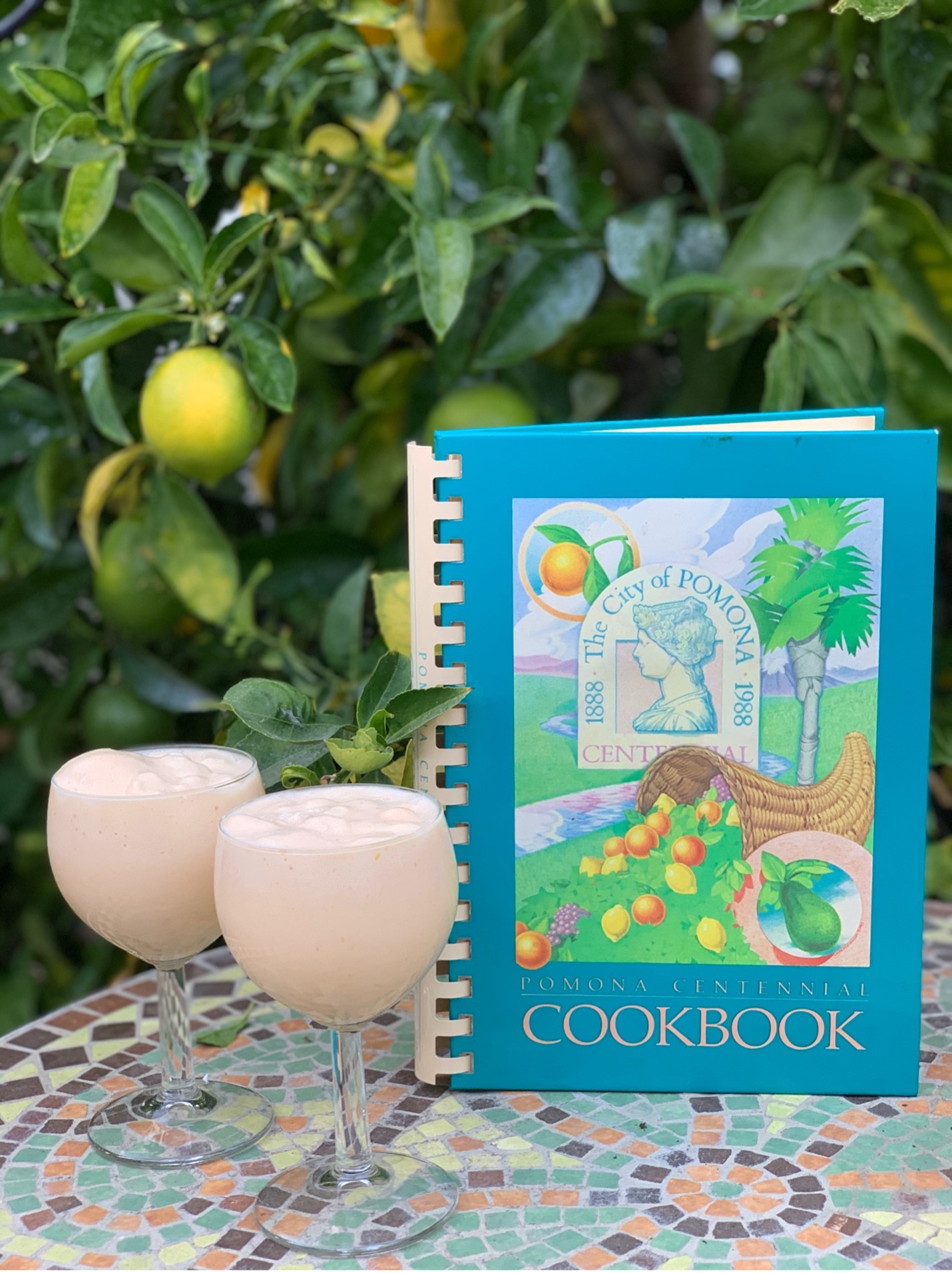

The books in the Community Cookbook Archive document Los Angeles stories through the lens of food. Recipes chart neighborhood demographic shifts, technological innovations in the kitchen, and wartime scarcity. Featured ingredients speak to Southern California’s unique food history. In Cooking the Native Way, produced in 2018 by the Chia Cafe Collective, you’ll find recipes utilizing acorn flour from native oaks, amongst many other Indigenous food sources. Southern California’s Spanish Mission-driven colonization of land and shift to agriculture is also evident, especially in the abundance of citrus recipes. The Pomona Centennial Cookbook from 1987 includes a recipe for “Hollywood Parade” punch, calling for one-quart orange juice and one-quart orange sherbert. Ahead of the recipe, the contributor, Marjorie Souther, writes, “My grandma Woodard moved to Pomona in 1923. She packed oranges all her life. This drink was served under the shade trees in the summertime before the days of air conditioning.”

It’s not uncommon for the books to take on a scrapbook quality with maps or custom artwork, such as the hand-stamped cover design of Comidas Mexicanas from 1937, a bilingual cookbook with recipes from women living in Pasadena’s Mexican communities. Many cookbooks also contain yearbook-style photographs of club members, places of worship, and images of significant Los Angeles architecture. A photo of the Philanthropy and Civics Club on S. Wilton Place—the former home of real estate developer and Crenshaw Boulevard namesake George Crenshaw—is featured in the opening pages of the club’s 1933 cookbook. The recipe collection preserves this since-demolished home’s grand facade, making it an unexpected vehicle for civic memory.

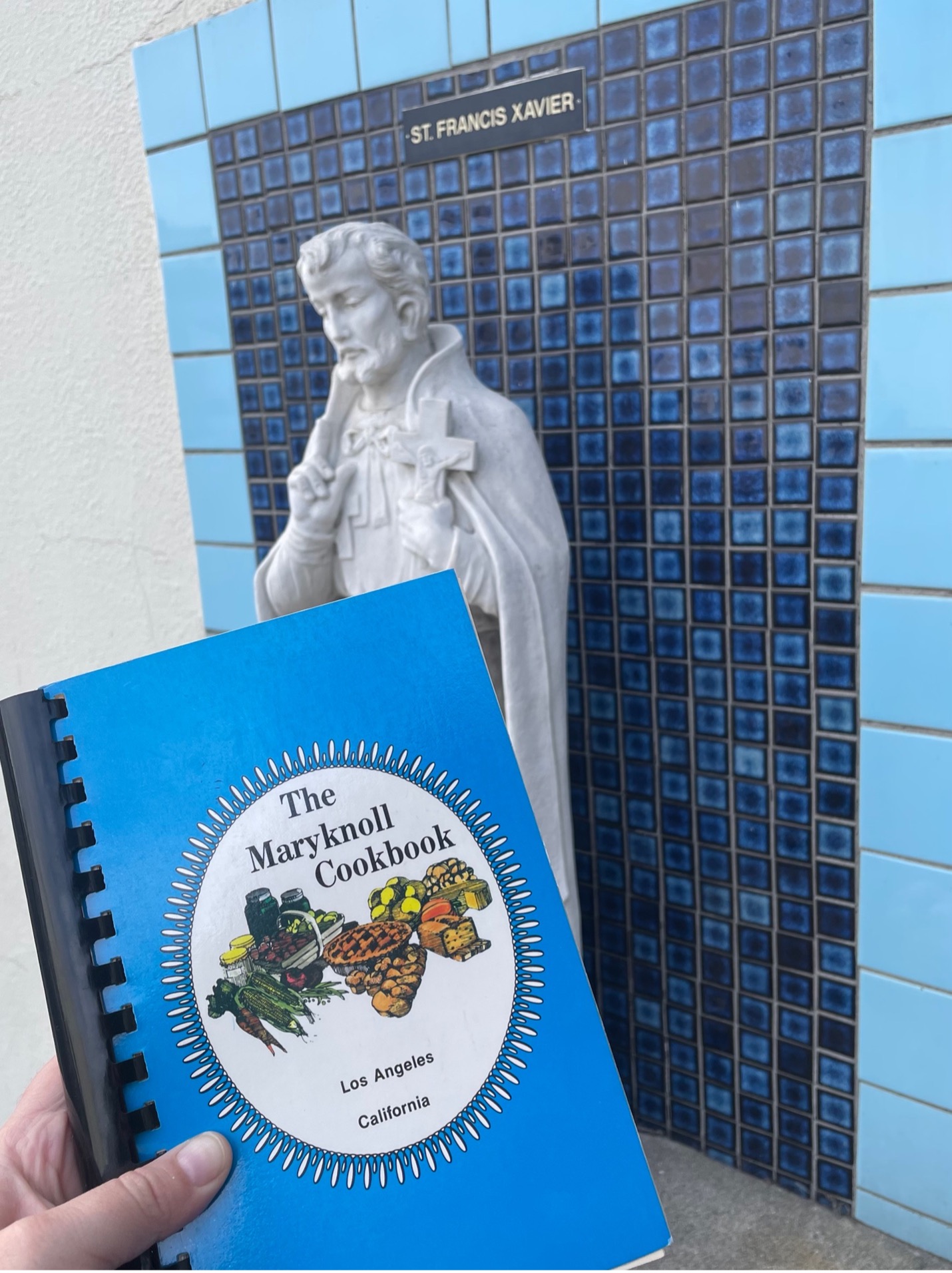

Often passed between individuals as gifts, community cookbooks also became trojan horses for personal histories. How We Cook in Los Angeles, published by the Ladies’ Social Circle of Simpson M.E. Church in 1894, features first-person essays amongst recipes for dishes like walnut cake and cucumber pickles. Almost a century later, The Maryknoll Cookbook, published in 1983 by downtown L.A.’s Maryknoll Japanese Catholic Center, also offers recipes for walnut cake and cucumber pickles. Yet this book, too, also gives us a window into Angelenos’ lives. It opens with a dedication to and profile of Sister Mary Bernadette Yoshimochi, who was born in Shiga, Japan, at the turn of the 20th century. Sister Bernadette became a nun in 1928, arriving in California a few years later, where she helped care for Japanese tuberculous patients at Maryknoll Sanitorium in Monrovia. The U.S. government incarcerated her in Manzanar during World War II, and afterward, she joined Maryknoll in Los Angeles.

I consider many community cookbooks to be subversive narratives, through stories like Sister Bernadette’s. They offer information that undermines or supplements the dominant, contemporaneous history of Los Angeles. In community cookbooks, local names appear in print that may not have been published anywhere else—even in phone books, which frequently only listed a household’s men, or in census data, due to systemic undercounting of certain demographics. A community cookbook’s list of contributors is, then, an alternative record of who lived, worked, cooked, and ate here.

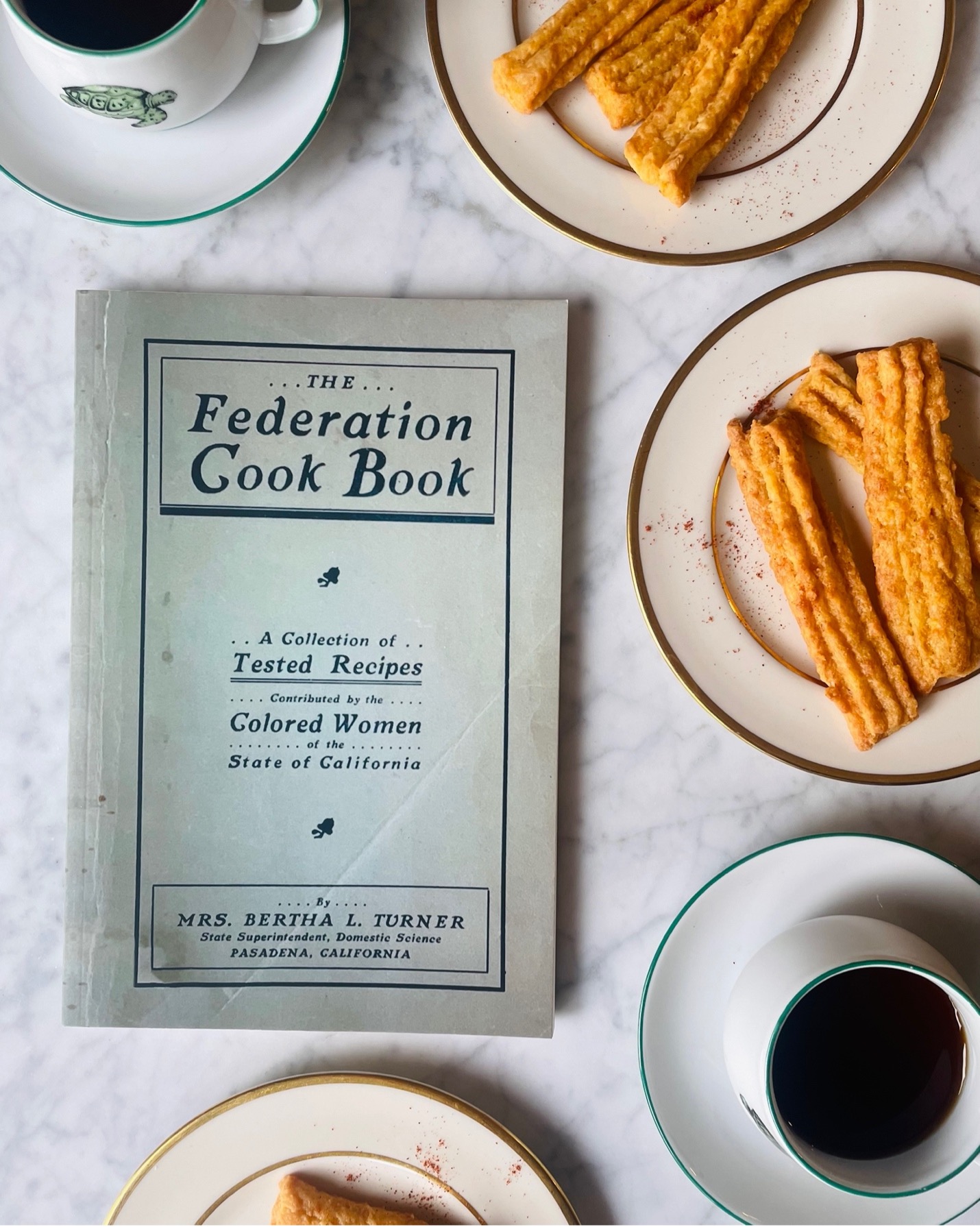

Beyond being primary source documents, community cookbooks are instruction manuals meant to be used in the here and now. Their “splash pages” are a testament to the volumes’ original utility. There’s something powerful about sitting down to a meal shared with someone who is no longer here. This is true whether you’re making suffragist and poet Eva Carter Buckner’s cheese straws, from the Federation Cook Book, published in Pasadena in 1910, or Anne Brunell’s “Pleasure Dome” liverwurst and cheese appetizer from UCLA Engineering’s Enjoy! Cookbook, undated, but likely from the late 1960s. Every time I cook from these books, I learn something new about Southern California—and see food as both a way of commemorating the past and an avenue for gathering together in the present.

Send A Letter To the Editors