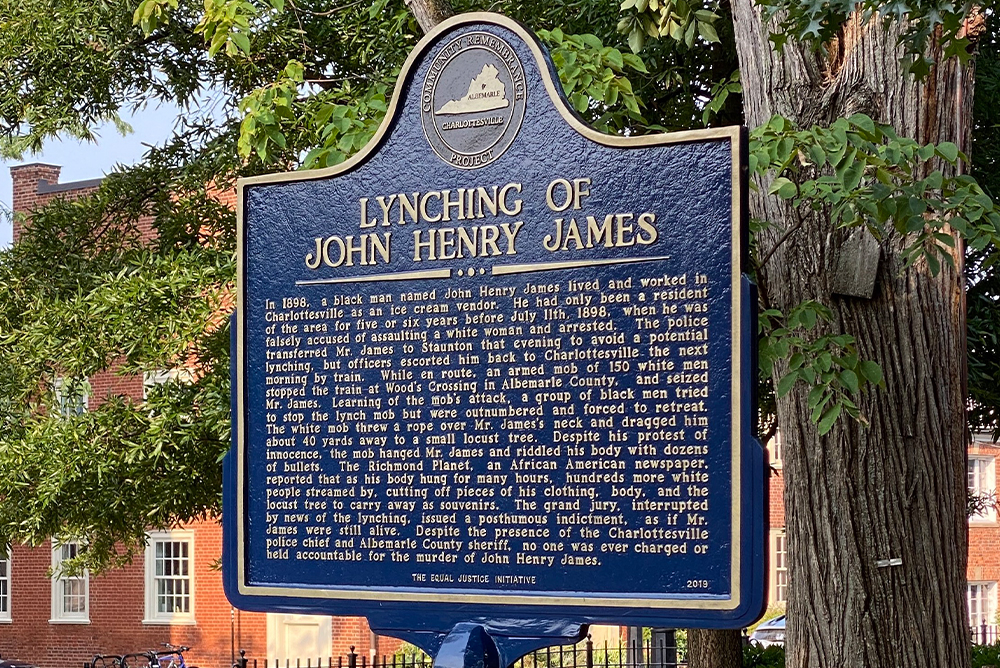

Margaret Burnham, director of the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project at Northeastern University, argues that it’s time for attorneys and courts in the U.S. and Southern states to revisit decades-old rape accusations, many of which led to lynchings of Black boys and men. Pictured above: a historical marker on the grounds of Virginia’s Albemarle County Courthouse commemorating lynch mob victim John Henry James, who was posthumously charged with rape. An Albermarle County judge threw out the 125-year-old indictment this year. Courtesy of Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society/Cvillepedia. Public domain.

This piece publishes alongside the Zócalo/Mellon Foundation program “How Does Confronting Our History Build a Better Future?” Read a summary of the event and watch the discussion here.

On July 12, 1898 John Henry James’ body, riddled with bullets, hanged from a locust tree. The Virginia man had been in the custody of the Albemarle County sheriff, awaiting grand jury action on a rape allegation, when a mob of 150 people kidnapped and killed him.

James, the story went, sexually assaulted one Julia Hotopp. (I belabor here, in confirming your suspicion that James was Black and Hotopp white.) There were doubts surrounding Hotopp’s allegation. Still, a newspaper applauded the mob, noting that “the people of Charlottesville heartily approve the lynching.” The grand jury, determined to have its say too, over a corpse no less, issued a posthumous indictment.

For more than a century, James was an accused rapist. He obtained a minuscule measure of justice on July 12, 2023—the 125th anniversary of his death—when Albemarle County prosecutor James Hingeley asked a circuit court to revisit the indictment, and judge Cheryl V. Higgins, at long last, dismissed it.

These officials are to be commended; criminal indictments do their best work in the universe of the living. James’ is an easy and instructive case, illustrating with blinding clarity the umbilical link between illegal lynching and state-sanctioned rape executions, two corporeal atrocities that were, infamously, pretty much reserved for Black males—boys, as well as men.

James’ exoneration is also a prophetic case. It demarcates a path forward for a crucial American reckoning with a thousand-plus state executions of Black males accused of assaulting white females, mostly in latter-day Confederate states, at the hands of a supremacist legal regime.

That John Henry James’ indictment came after his lynching may seem absurd—but in 1898, and for decades thereafter, such was the symbiotic common ground between the county courthouse and the lynching locale. Legal officials raced against the mob to confer upon these killings the stamp of validity, and lynching parties, enacting “lynch law,” adorned their proceedings with the rituals of the courtroom. Lynchings were extensions and expressions of the administration of justice, not estranged from it. A case in point: in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1917, a group of men known as the Shelby Avengers announced their intention to lynch a man charged with the sexual assault and murder of a white teenager, giving people ample time to reach the location where, they promised, justice would be dispensed. After the man was burned, decapitated, and dismembered, the Commercial Appeal reported, “throughout the entire proceedings there was perfect order … and none offered violence not countenanced by the summary court.” The newspaper also complimented the Avengers for having the forethought to appoint a treasurer to secure compensation for those participants who had absented themselves from work to search for and lynch the man. Jury duty.

This pattern persisted from the end of the Civil War until the early 20th century. Beginning around 1909, with the introduction of the electric chair, the numbers of legal executions rose, slowly replacing extralegal lynchings, at least in Virginia. Some scholars of lynching—Fitzhugh Brundage, for example—have expressed skepticism that a rise in legal execution in the early 20th century correlated with a decline in extralegal lynching. But the historical record is replete with evidence that executions were understood to be a replacement for the mob, particularly in Virginia.

From 1880 to 1909, 27 Black men were lynched in Virginia for rape or attempted rape, while just seven were lynched in the four decades that followed. From 1908 to 1965, Virginia executed 56 men on non-lethal sexual assault charges. All of them were Black. These numbers are not anomalous: 19th-century versions of the state’s rape laws explicitly split white rape from Black rape. Before the Civil War, only “free negroes” charged with assault against white females were subject to the death penalty; the penalty for white males was limited to a 10- to 20-year prison term. Over its entire 400-year history, the state killed just three white men for rape, all before 1868, and no white man was ever put to death for attempted rape while 36 Black men suffered that fate—one as late as 1940.

In 1921, the state’s highest court made the connection between the rise in executions and the decline in lynching explicit. In Hart v. Commonwealth, a case sanctioning the execution of a 21-year-old for attempted rape and rejecting his argument that the sentence constituted cruel and unusual punishment, the Virginia court opined that “the likelihood of the resort to lynch law, unless there is a prompt conviction and a severe penalty imposed. . . is well known to exist.” (Indeed the state apparently deemed attempted rape more heinous than attempted murder—an offense for which no one in Virginia, Black or white, was executed after 1863.)

For decades to follow, Virginia’s Supreme Court—comprised entirely of white male jurists—aided and abetted what U.S. Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun later described as a “machinery of death.” From 1908 to 1963, the court wrote opinions in 73 capital and non-capital cases of rape and related crimes; they reversed the sentences of approximately one-quarter of Black defendants compared to nearly two-thirds of white defendants.

Other states enforced similar laws. Louisiana also ran a two-tiered legal regime for rape prosecutions, effectively reserving its capital penalty for Black defendants charged with sexual assault on whites. Since 1900, the state has executed around 40 defendants for aggravated rape; all but two were Black. It has never executed a white man for the rape of a Black woman. South Carolina has, since 1900, executed around 66 people for sexual crimes, of whom 61 were Black. Florida has executed 48 men for rape and related crimes, of whom 44 were Black. And in Georgia, since 1900, 87 of the 93 men executed by the state for rape have been Black.

The U.S. Supreme Court declared the death penalty for rape unconstitutional in 1977. But its decision in Coker v. Georgia hinged on the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment, and never addressed the penalty’s longstanding racial intent and impact. Had it done so, lower courts might have been on notice to protect against unconstitutional bias in the administration of rape laws by, for example, ensuring fair and deracialized jury selection, protecting against discriminatory prosecution, and guarding against the race tax in sentencing.

Instead, the execrable history of lynching and execution continued to infect rape prosecutions. Until DNA forensics became widely available about 20 years ago, countless innocent Black men were wrongly convicted for sexual assault. Just 10 years ago, Black people were almost eight times more likely than white people to be falsely convicted of rape. And just last year, the National Registry of Exonerations reported that Black prisoners incarcerated for sexual assault are over three times more likely to be innocent of the crime than white prisoners—and generally received far longer sentences than white exonerees.

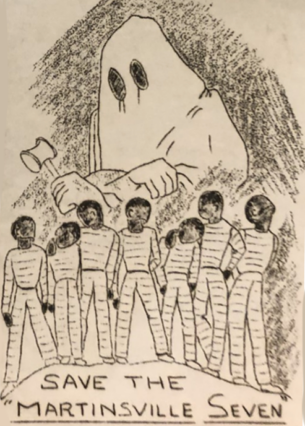

This is not just a Virginia problem. But Virginians are grappling with this history head-on, and could lead the nation in a project of redress. The state recently abolished the death penalty, in 2021. That year, then-governor Ralph Northam posthumously pardoned seven men who were executed after conviction on a 1951 rape charge that attracted international protest. Descendants of the Martinsville Seven, as the accused were known, had campaigned for the pardon. Northam was careful to specify that the pardon was not an exoneration; it was an acknowledgment that the men did not get a fair trial. “We all deserve a criminal justice system that is fair, equal, and gets it right,” he proclaimed.

This illustration was part of a 1951 Michigan petition mailed to then-Virginia Governor John S. Battle to save the “Martinsville Seven.” Their executions were carried out despite pleas for mercy from around the world. Image courtesy of the Library of Virginia.

By that measure—one none could quarrel with—there are, nationally, 1,073 rape executions that deserve posthumous redress. States could aim to correct these travesties by executive pardon, as with the Martinsville Seven, or by judicial action, as with John Henry James. The U.S. courts might start admitting their own complicity in rushing Black men to their deaths. Localities might consider how prosecutors’ offices, like that of Albemarle County, can review historical cases to determine how many were rushed to judgment to avert mob violence, or otherwise shortchanged the process that was the defendant’s due. They might also examine the actions of police, who often railroaded accused men by threatening to turn them over to the mob if they did not “confess.”

Manifestly, not every Black man executed for rape was innocent of the charge. But because none of these men got the due process or sentencing justice they deserved, perhaps all their cases must be re-examined. All of these men were hostages in the war for white supremacy. All of them were subjected to the meta-law of race. And all of them experienced law as a political weapon, rather than a set of neutral evidentiary rules.

State-endorsed redress and remedial measures, while inevitably insufficient, will help. They would also expiate slanders and stereotypes that, even in today’s courts and prosecutors’ offices, render the Black male “naturally” a potent threat to white females. When Dylann Roof shot down parishioners at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015, his battle cry evinced the abiding nature of this group libel. “Y’all are raping our white women, y’all are taking over the world,” he yelled, as he slaughtered.

The new sits solidly on top of the old here; race is the beginning and the end of this ongoing horror story. There is work to do, and Charlottesville prosecutors have sharpened their pencils and stretched their (and our) imaginations. The James case makes clear that the crimes of racialized justice must be lifted from the pages of books, criminology journals, and amicus briefs and placed in the public square. There, they can stimulate a community’s “ongoing commitment to . . . racial justice” and demonstrate the “importance of community remembrance projects,” as Hingeley, the prosecutor who helped clear James, observed.

The more of these historical travesties we tackle, the better off our legal system, and our nation, will be.

Send A Letter To the Editors