Pundits have branded this primary presidential campaign season as the most vitriolic in history. Negative commercials dominate the airwaves.

How did we get here? Mad Men has the answer, of course.

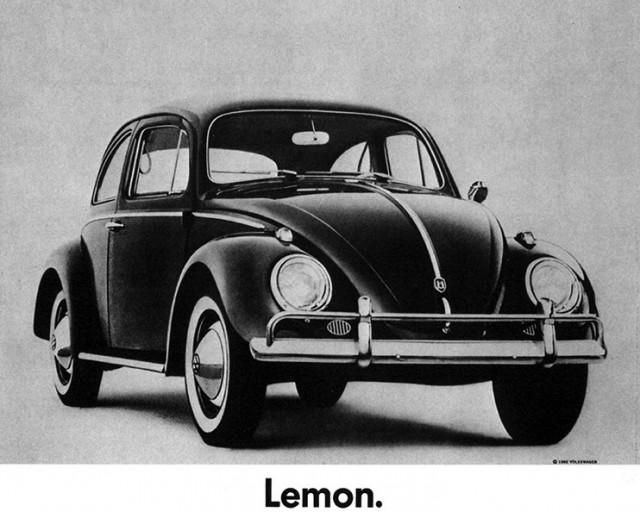

During an episode from the first season of the show, fictional advertising executive Don Draper expresses revulsion for a self-deprecating Volkswagen print ad. It was part of a real, groundbreaking whimsical campaign from the 1960s that included several legendary ads–the “Lemon” spot Draper despises, “Think Small,” and later the “Snow Plow” television commercial. The campaign was innovative because of its refreshing honesty, which caught the eye of John F. Kennedy and later grabbed the attention of the Democratic National Committee staffers plotting the media campaign for Lyndon B. Johnson.

But Draper didn’t know that yet. “I don’t know what I hate about it the most–the ad or the car,” Draper barks to a group of colleagues. What incites his ire? The copy, underneath a large picture of a seemingly spotless car, begins, “This Volkswagen missed the boat. The chrome strip on the glove compartment is blemished and must be replaced. Chances are you wouldn’t have noticed it; Inspector Kurt Kroner did.” The ad seeks to highlight Volkswagen’s superior inspection process, and to assure consumers, “We pluck the lemons; you get the plums.”

After his team argues about the ad’s effectiveness, Draper grimly acknowledges, “Love it or hate it, the fact remains, we’ve been talking about this for the last 15 minutes.”

Draper is right–the ad worked. But it’s somewhat paradoxical that this poignant, funny campaign eventually spawned a new advertising category: the political attack commercial.

Advertising agency Doyle Dane Berbach went from scrappy to formidable on the basis of the Volkswagen campaign, which auto journalist David Kiley described as being more “prose more than copywriting,” and “different from anything else the U.S. magazine reader had seen. It was the first time anyone took a realistic approach to advertising. It was the first time the advertiser ever talked to the consumer as though he was a grownup instead of a baby.” The commercial for the VW bug (“Have you ever wondered how the man who drives the snowplow drives to the snowplow?”) is often cited as one of the greatest commercials of all time.

Kennedy was so impressed by the ads that he asked his brother-in-law, Stephen Smith, to find out if DDB would work on his 1964 campaign.

After Kennedy’s assassination, Lloyd Wright of the Democratic National Committee was tasked with finding an advertising agency for Lyndon B. Johnson’s campaign. According to Robert Mann’s Daisy Petals and Mushroom Clouds, Wright, an advertising aficionado and admirer of DDB’s work, urged the DNC to choose the New York firm over Chicago-based Grant Advertising. But DNC Treasurer Richard “Dick” Maguire and Chairman John Bailey rejected the idea because DDB was too expensive.

Wright wouldn’t take no for an answer. In a March 11, 1964 memo to Johnson’s aide and White House staff members, who had the ultimate say in deciding which firm to hire, he wrote: “I have counseled with the most respected men in the industry about this matter and without exception, they say DDB is by far the best … DDB is today recognized as one of the top agencies in the business.” The DNC hired DDB for the campaign on March 19.

For six months, a team of 40 DDB art directors, TV producers, and copywriters set to work on what would become the most famous political ad of all time–and the granddaddy of all negative political ads.

The Daisy ad, which aired only once (during the September 7 NBC broadcast of Monday Night at the Movies) features a little girl innocently counting petals as she plucks them off of a flower. Her sweet voice fades into a male announcer’s countdown to a bomb detonation. After the nuclear explosion, he tells Americans why they should vote for President Johnson. “These are the stakes. To make a world in which all of God’s children can live, or to go into the dark. We must either love each other, or we must die. Vote for President Johnson on November 3. The stakes are too high to stay home. ”

Not subtle, but the DDB team was capitalizing on Republican challenger Barry Goldwater’s threats to use nuclear weapons against Communists in Vietnam and Laos.

“What we tried to do was look at what Goldwater had [truthfully] said, and present it in an unusual and bold way,” Sid Myers, one of the original art directors on the DDB team, explained to me earlier this year. “It was sort of a crusade–we were really fighting this guy.”

Myers said the team never intended to create an “attack” ad, let alone an entire genre that has come to dominate electoral discourse. “This was the way we used to do work for national clients–we did unusual, impactful kind of work,” he said. “There wasn’t a special sit-down where we said, ‘We’re going to just do attack ads, or dirty ads.’”

But Daisy produced a political world in which most interactions between political campaigns and their marketing teams would focus intently on how to take out the opposition. Mad men can be very persuasive when convincing people that someone on the ballot is, well, a mad man.

Elizabeth Weingarten is editorial assistant at the New America Foundation.

*Photo courtesy of alanmx.

Send A Letter To the Editors