Wildly famous. Frequently scandalous. Speakers of truth to power. Action heroes. Acclaimed by the people. Romantic, rebellious, charismatic, inspirational. These were just a few of the ways saints were described at a Zócalo/Getty panel that asked a group of scholars of art, history, and religion, “Why Do We Need Saints?”

Documentary filmmaker Jody Hassett Sanchez, the evening’s moderator, opened the discussion by asking the panel, “Were saints the celebrities of their day?”

Yes, said UC Riverside medieval art historian Conrad Rudolph. Not everyone wanted to be a saint, but many of the saints-to-be were mobbed like contemporary soccer stars. They were also, he said, people who took a stance against contemporary expectations.

University of Notre Dame theologian Candida Moss stressed that saints were hardly placid figures in their day. “We think of them as sort of quiet and peaceful and always praying,” she said. “But they had these scandalous backgrounds and these deeply erotic relationships with Jesus.”

One typical early Christian saint, said Rudolph, was a young woman whose father was fighting against the Christians. When he discovered that she was a Christian, he had her executed. But an act such as this alone wasn’t enough for sainthood.

To become a saint generally required charisma and an ability to inspire people; once you got enough local support, people would claim you and spread the message of your saintliness. After the Protestant Reformation, the process became more codified.

Cabrini College folklorist Leonard Primiano explained what the process of canonization involves in the 20th and 21st centuries. First, you must be dead. Next, in order to become venerable, someone (like a graduate school student) will study your life and make sure you weren’t overly scandalous. Then comes proof of miracles for first beatification and then canonization. (The term “devil’s advocate” was originally used to describe the person responsible for finding fault with a potential saint’s claim, explained Rudolph.)

It’s possible, said Hassett Sanchez, to be “unsainted.” Some of the most popular saints—Christopher, Catherine—were actually unsainted in 1969. How did this happen?

Moss explained that in response to criticism from Protestants, the Catholic Church had to investigate the historical evidence for the lives of the saints. In cases where the evidence was insufficient, people were unsainted. However, ordinary believers have pushed back. “People venerate whom they venerate,” Moss said.

Primiano added that unsainting simply means taking a saint’s day off the universal calendar of the Church; it doesn’t mean complete erasure.

Do people pray to saints or with them? How exactly do saints intercede with God?

Rudolph said that no one worships saints; people venerate them. Through a saint, that veneration passes on to God. In the Middle Ages, if you were a peasant, you couldn’t approach anyone at the top of the earthly hierarchy, so you would find an intercessor to communicate on your behalf—a knight, say, to implore the feudal lord for you. The same went for a peasant’s relationship with God; a saint was required as a go-between.

In the Middle Ages, people would travel to holy places on pilgrimages to venerate relics—parts of the saints’ bodies. This wasn’t just about visiting an old bone in a box. It also involved going to one of the few places where one could experience images—art. And, at that time, seeing people or events depicted as works of art essentially made them real.

Standing at an altar with stained glass windows and light flowing through, said Moss, was a holy experience for these pilgrims. “The boundaries between heaven and earth collapse,” she said. “And you get to come into contact with the divine.”

But people also wanted to come into contact with the saints in other ways. Some tombs were designed so people could crawl into cubbyhole-type openings and spend time with the bones. Pilgrims would also drink water that had been consecrated with a drop of a saint’s blood—or drink water into which a mummified saint’s hand had been dipped. They believed that drinking the water that had been used to wash a saint’s body could bring miraculous cures.

Why, asked Hassett Sanchez, are the images of the saints so gruesome?

“The idea was, the more you suffered, the greater witness you made for Christ,” said Rudolph. “It was also good PR.” Saints competed for the more impressive stories and miracles.

The images grow more violent as times passes, said Moss, because the competition between saints grew more intense. And in the Middle Ages, pain and truth were believed to be tied closely together, so the more a saint could endure torture, the more that he or she said was true.

What role do the saints play in contemporary faith?

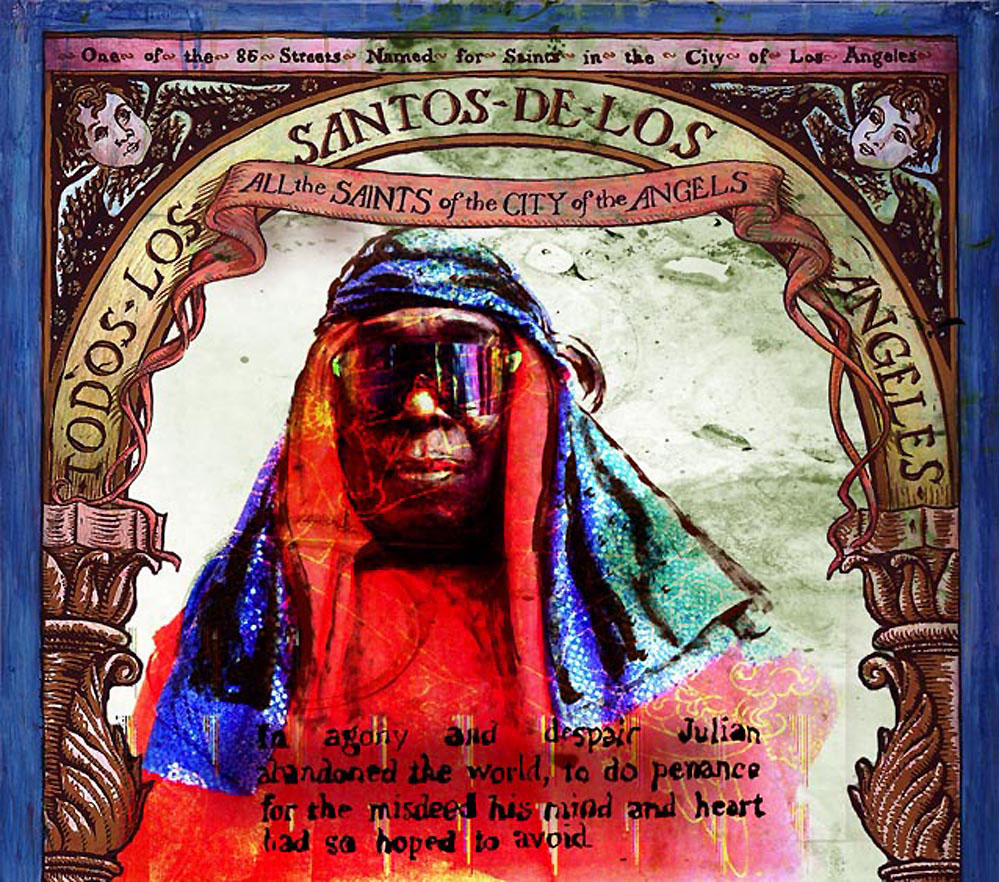

The most popular folk saint today, said Primiano, is Santa Muerta, the patron saint of prostitutes and drug dealers. Santa Muerta emerged out of pre-Colombian civilization and has been condemned by the Catholic Church. But people of all kinds still pray to her for help with economic matters, and her popularity has grown in the 21st century, particularly among Mexicans and Mexican-Americans. Saints, said Primiano, are as important in certain people’s lives as ever. “Just when we think the world is getting secular, it’s not,” he said. “It’s just as interested in religion as ever.”

Send A Letter To the Editors