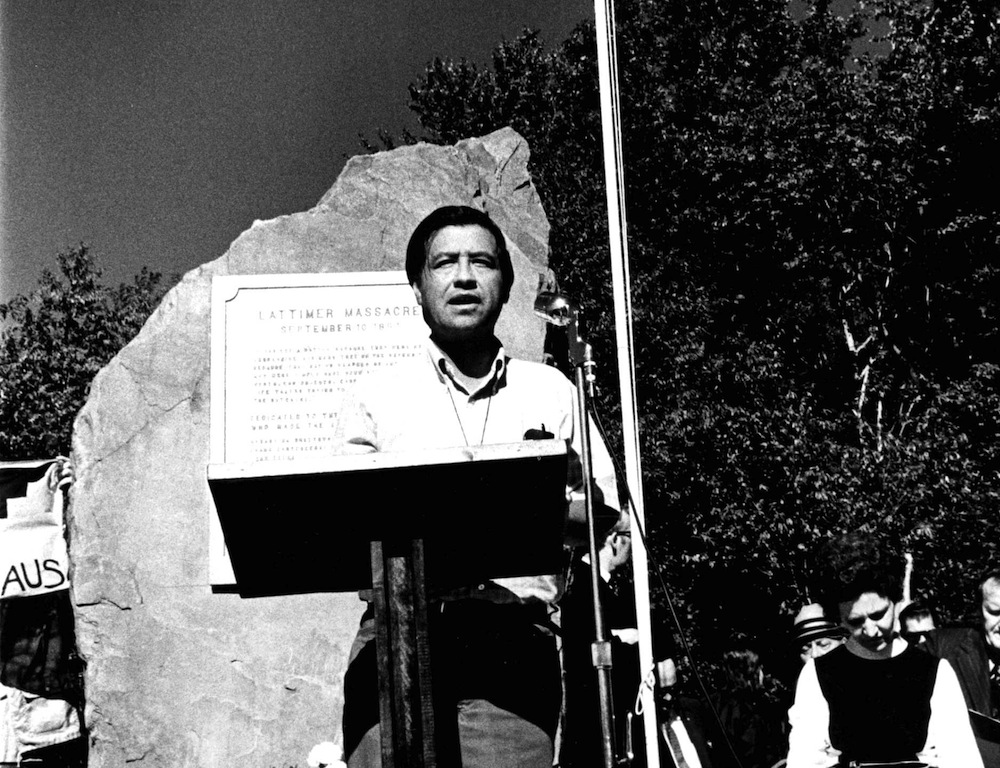

Cesar Chavez speaks at the dedication of the Lattimer Massacre Memorial, Lattimer, Pennsylvania on Sept. 10, 1972. Courtesy of H. Scott Heist/Globe Photos, Inc.

Of all the stories I’ve held on to from my time working for Cesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers, the one I like to tell is not from the fields of California but from the mines of Pennsylvania. It involves not only Cesar, but also a helicopter and a man named Flood.

My journey to working with the farmworkers had been an indirect one. I grew up mostly in Rialto, California, where my first successful organizing project involved getting my fellow Eisenhower High students to stage a sit-down strike until we were allowed to wear T-shirts on hot days. From there, I was inspired by some combination of President Kennedy’s example, the reading I did at San Bernardino Valley College, and my time as a VISTA worker to think about a career where I could help to change society. A Presbyterian pastor in Colton introduced me to the farmworkers movement, and soon I found myself part of the grape boycott. In the summer of 1968, I picketed with Cesar’s nephew, Freddy Chavez, at Ralph’s on Vermont Avenue in South L.A.

My final two years in college were at San Diego State University. During my second year, a tomato strike took place in San Ysidro in the southern part of San Diego County. I started volunteering to line up support for the strikers among church groups. After a few weeks, it turned into a full-time job, which led to me flunking out of school. The strike lasted for about nine months and after it ended, I moved north to Napa Valley to organize in the wine grape industry. After a few months, I was sent off to Philadelphia to work on the national lettuce boycott.

I’d first seen Cesar in 1970 at the signing of the contract in Delano, California that ended the grape boycott. I later talked strategy with him during the tomato strike in San Ysidro. But going east brought us into closer contact. When Cesar came to Philadelphia, I would drive him to various meetings. A group of us went with Cesar to the United Auto Workers convention in Atlantic City. Another time, my colleagues and I drove him to New York for meetings, and I got a glimpse of his sense of humor. As we drove up to a tollbooth on the New Jersey Turnpike, he asked me whether I had seen The Godfather and remembered the scene where Sonny got whacked at a tollbooth. Fortunately, I hadn’t—because I was plenty nervous driving Cesar to begin with.

On these trips, he was very friendly and curious about our day-to-day work. He wanted to know how the lettuce boycott was working. He loved talking about organizing and getting ideas about how to organize more supporters for the boycott. But he could also be very businesslike. Cesar had two beautiful dogs, German shepherds named Boycott and Huelga, who followed him everywhere. They were very well-trained security dogs that often walked beside Cesar. One day, Cesar was trying to start a meeting, but none of us would quiet down. All of a sudden, Huelga jumped up on a table and barked, loudly and with authority. The meeting started.

But the time with Cesar I remember best was in 1972, when he came to Philadelphia, and my colleagues and I drove him up to Lattimer, in Pennsylvania coal country. He had been invited to speak at an event with the United Mine Workers, an important opportunity to build solidarity with our brothers and sisters in the labor movement.

The occasion was historical—it was the 75th anniversary of a terrible and famous event in 1897 when sheriff’s deputies shot down 19 striking miners as they marched in Lattimer to demand union recognition. According to Michael Novak’s 1978 book The Guns of Lattimer, deputies had spent the morning joking about how many miners they would kill. Later that day, after a march and confrontation with authorities, the miners began to disperse—but the deputies began shooting, killing 19 people. Every miner who was fatally shot that day was shot in the back.

When we arrived, American flags were everywhere. Church chimes were playing union songs. Cesar began his speech by thanking all the attendees. He then walked the crowd through the tragic events of 1897, linking the struggle of those miners with today’s farmworkers.

“We know only too well the hardship and sacrifice of these mineworkers back on September 10, 1897. For here is a group of workers in America today whose lives so closely parallel the lives of those miners,” Cesar said. “They too are immigrants; they too have strange-sounding names; they too speak a foreign language; they too are trying to build a union; they too face hostile sheriffs and recalcitrant employers; they too are non-violent, as these men were.”

He then inspired the crowd to think and act toward the future. “Let there be strength and unity in the ranks of labor throughout this land; let there be only one voice; let there be only one Lattimer; let there be peace; let there be justice; let there be love. Amen.”

At the end of the speech, the crowd jumped to its feet and applauded for many minutes. The spirit of solidarity that day—and Cesar’s message of the universality of the struggle for decent wages, safe working conditions, and good benefits—was powerful.

But the speech was not the whole story. While we were all still assembled, a helicopter appeared from over a mountain ridge. The chopper hovered above the crowd and gently landed—right into the audience. No one ran; they just moved out of the way. As the helicopter touched earth, a side door opened and out walked, down a ladder, Congressman Dan Flood.

Flood was a Pennsylvania native who had trained as a Shakespearean actor before finding the law and eventually politics. According to William C. Kashatus’ 2010 biography of Flood, he was an old-time mover and shaker on Capitol Hill who wore white linen suits, silk top hats, and dark flowing capes on the House floor. A former vaudevillian, he turned addresses and arguments into old-fashioned, stage-actor performances.

On this day in Lattimer, Flood seemed particularly exuberant. An account of that day in the publication Out Now matches my recollection of “the sudden arrival of a large green Army helicopter … and out jumps this older fellow with a wax mustache wearing a red cape and tuxedo.”

The audience erupted into a cheering frenzy, and as those cheers got louder, the congressman walked through the crowd, shaking hands, kissing babies, and saying hello. He got to the stage and enthusiastically shook Cesar’s hand. He than sat next to Cesar and began hugging him, slapping his leg as a friendly gesture. Cesar accepted it all in a most kind manner. Then, a local group of union members marched to the front of the crowd and played “The Star-Spangled Banner.” A local clergyperson said a prayer and—like clockwork—the union chimes on top of a nearby building played the Woody Guthrie tune “Union Maid.”

Flood was introduced, and his first words, offered with dramatic flair, were as follows: “I have come here to praise Cesar.” The crowd stood up and cheered. Again, Flood, arms raised and cape flowing from a light breeze, said, a second time, “I have come here to praise Cesar!”

No one within 50 miles of that stage remained sitting. His showmanship, and the colorful nature of his dress and appearance, was incredible. Flood was beloved by the people he represented. And he made it abundantly clear that the leader of this robust, exciting farmworkers movement was a brother to every single person there.

It was a moment of labor movement unity, of profound connection, and of patriotism. It has never left me.

I have told this story many times over the years. I had many great days as an organizer for the union, but none better than this one.

Send A Letter To the Editors