San Bernardino is often described as the second-poorest city in America and it is a violent place. It will never be a healthy place—cannot be a healthy place—until we stop the violence. The conventional approaches—heavy policing, targeting gangs—have been tried and they haven’t worked. As deaths from violent crime have fallen around the country, they have not budged here. And so we started walking.

San Bernardino is often described as the second-poorest city in America and it is a violent place. It will never be a healthy place—cannot be a healthy place—until we stop the violence. The conventional approaches—heavy policing, targeting gangs—have been tried and they haven’t worked. As deaths from violent crime have fallen around the country, they have not budged here. And so we started walking.

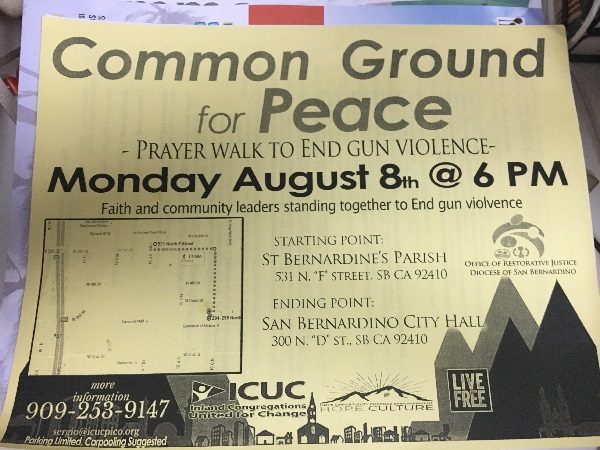

That sounds like a trivial thing, but it’s not. We’re bringing people together to walk at night, to pray together, to talk about life—not death—and really to change the narrative of our city. It’s a message that is not about incarceration. We say, “We want people alive and free.”

I grew up in Iowa, in a white working-class family. My dad was a social worker, and I was introduced to charity work through him. I was in college in the 1970s at Notre Dame. There I met priests who had been exiled during the military dictatorship in Peru. I spent time in Peru and in Chile, living in extreme poverty, working to help try to alleviate some of the injustice. In 1998 friends invited me to work with them in San Bernardino. I’d never been to California, but I looked at the city of San Bernardino, at both the need and the hope, and I recognized a lot of what I’d seen in Latin America, and I knew there was an opportunity here to do something that could make a difference.

I joined Inland Congregations United for Change in 2005, right when it was founded. In that year there were 52 murders, 15 of them children under the age of 18. Every month a kid under 18 was getting killed.

Fast-forward to 2016. With more than two months left in the year we’ve already seen 52 slayings. This is a steep increase from last year’s 44 homicides, which included the 14 people killed by terrorists at the Inland Regional Center. The youngest victim through early October of this year was Travon Williams, a child of just 9, shot in the head on a July night while he was with his father, who was also shot to death. More than a thousand people came to their funeral. A few months earlier, 12-year-old Jason Spears was shot dead walking home from the market near his house.

We know that the people in San Bernardino who are shooting and killing people account for one half of one percent of the population. That’s 100 people. There must be a way to turn that around.

Two years ago, Inland Congregations United for Change started advocating to the city that they adopt the Ceasefire model. This is a program that started in Boston 20 years ago that has been adopted in cities across the country. In Oakland it seems to be making a difference and in Stockton it decreased homicides by 43 percent. It involves local officials and community leaders “calling in” suspected gang members and offering them counseling and support services and employment—if they agree to put down their guns.

To start the process we walk into neighborhoods and invite people into an accountability session. All of the community partners are there—police, mental health, housing, job training and employment. We invite the people who are involved in the violence and we tell that person we know they’re involved in this. Then we say: “Look at what we’re offering you. We want to work with you. We don’t want you incarcerated. We want you free and alive.”

This is a big change. It’s about changing the mentality about how we address violence. The challenge now is to get the city to try it. And so we walk, twice a month, sometimes three times a month. In the evenings, after work. The turnout is very strong. We have 25 clergy representing a diverse array of faiths, Catholic, Baptist, Muslim, Jewish. We have 200 or 300 people walking. We pick three places of worship in a very heavily impacted area, in an area that has seen a lot of hardship and violence, and we walk from one to the next.

We start at one house of worship and we pray together. We talk about how Ceasefire works. Members of the community speak the names of friends, family, and neighbors who have perished. We have a display made up consisting of what look like painted popsicle sticks—one for each person who has been killed. Then the clergy call out the names of every city council member, and we say, “Councilmember XYZ, we see you.”

And then we march together through the streets, chanting, “Alive and free, that’s what we want to be.” The point is to walk through the neighborhoods and make contact with neighbors and families, parents and grandparents, children and grandchildren. People are out in their yards, walking down the street. We talk with them and some of them join us.

We aim for what we call a prophetic tone. We have a vision of a different community. We have a clear message to the community about living alive and living free, and a clear message to our political leaders that there are solutions to the gun violence that are working, that other communities are embracing and we are calling on them, very boldly, to be supportive.

To get our city leaders on board, we know we need to change the way they think about the community. The common narrative of San Bernardino is that this used to be an “All-American City.” There’s a big sign downtown to that effect. The story goes that San Bernardino was a kind of nirvana until the economy started to go down. Norton Air Force Base closed; Kaiser Steel in Fontana shut down; and BNSF Railroad moved to Kansas City. The narrative is these businesses left and then the city started to go downhill, the working people went to Kansas City, and the people with good jobs moved elsewhere.

That story continues like this: Then all the poor people came in and brought crime. That’s a dog whistle meaning that black people and undocumented Latinos were gang bangers and criminals who created all this violence.

But if you look deeper, what you discover is that the narrative about the fall of San Bernardino is full of holes. Violence in this city has been here for a long, long time. An important part of the San Bernardino story is about groups who have been denied access to opportunity while other groups of people have held on to their opportunity.

When African Americans came to the Inland Empire, after slavery and Jim Crow, cities like San Bernardino were totally segregated, a separation that held until not that long ago. For decades, if you were Latino or black you could not go to the white schools.

Even the name “Inland Empire” makes some people uncomfortable. It may conjure the seemingly endless citrus groves that used to cover the region, but for some people it sounds too much like the “Invisible Empire” of the Ku Klux Klan, which maintained a large presence in the area in the mid-20th century. This was the so-called “All American” idyll.

So where are we now? The dominant narrative is that people who live in poor, dangerous neighborhoods are valueless—not worthy of being helped and supported, with nothing to contribute. That is just not true. In every neighborhood there are incredible, good-hearted people who want to improve their lives and live in safety.

There’s a lot going on in our community: There are neighbors, family, and friends taking care of each other, overcoming poverty and exclusion, and finding ways to thrive. One example: air pollution in some neighborhoods regularly exceeds health safety standards—there are many days of the year when outdoor physical activity is not recommended. So we have groups of high school and college kids who have gone into the churches and schools and community centers to create youth-friendly activities, places to create art, and programs to explore forms of personal expression in a safe setting.

The young people here are a gold mine, but we are shortchanging them at every turn. The poorest neighborhoods have no parks. Of the children who graduate from high school in San Bernardino, a full 85 percent do not have the credits required for admission to college.

Over the past 10 years ICUC has mounted some very successful campaigns and some that have not been as successful. We’ve advocated for a range of programs for youth, and we’ve focused a lot of effort on the schools.

That’s great, but it’s not stopping the violence. It’s not enough to change the narrative.

In July, on the day of one of our marches, I read in the newspaper that the mayor and two councilmembers had gone to Oakland to study the Ceasefire program. That night at the march, I was standing with about 200 people. I looked up, and there was the mayor, standing next to me. I don’t think he knew who I was. I said, “Hey, I understand you went to Oakland, to look at their Ceasefire program. How did it go?” He said, “It went really well.” I asked him if he thought San Bernardino might give it a try. He said, “Yes, maybe. Thanks for asking.”

That’s how change happens. One hair at a time.

Send A Letter To the Editors