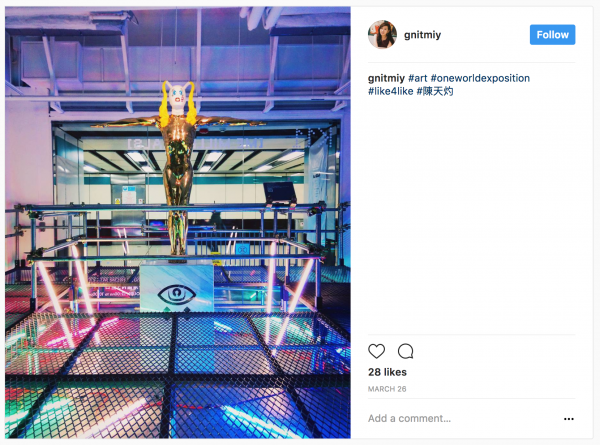

In some art museums, taking photos is forbidden. But using Snapchat, Instagram and other social media were actively encouraged at the exhibition One World Exposition #like4like, featuring 18 millennial media artists from Hong Kong and mainland China, at K11, a shopping mall blended with art galleries. It attracted more than 15,000 visitors within two months. It also went massively viral on social media. Photo courtesy of @wlwonglamb/Instagram.

Even a few years ago, galleries and museums that showcased their collections via Instagram were a minority. Now Instagram is ubiquitous. Cellphone cameras have officially replaced sketching among museum-goers. Social media mediates everything. And many art institutions have acknowledged the role of social media as a key aspect of audience engagement. To shape that role, art engagement, branding, and promotion all deserve a thorough reconsideration.

I learned more about how to do that a few months ago, through a show I curated called One World Exposition #like4like. The exhibition, which presented 18 millennial media artists from Hong Kong and mainland China, took place at K11, a shopping mall blended with art galleries. It attracted more than 15,000 visitors within two months. It also went massively viral on social media. During its two-month exhibition period, #like4like appeared in more than a thousand photographs by visitors and became the most hashtagged and geotagged exhibition on Instagram in Hong Kong.

What were the reasons for this success?

One reason is content. In recent years, the heated art market has transformed artwork into a highly profitable commodity, creating a phenomenon of excessive commoditization. Many artworks are produced to be desirable in the art market, resulting in many easy-on-the-eye artworks shown in exhibitions and art fairs. At a time when nonprofit institutions, commercial galleries and auction houses are undergoing a process of corporatization and global expansion, many argue that the disengagement of art has already taken place.

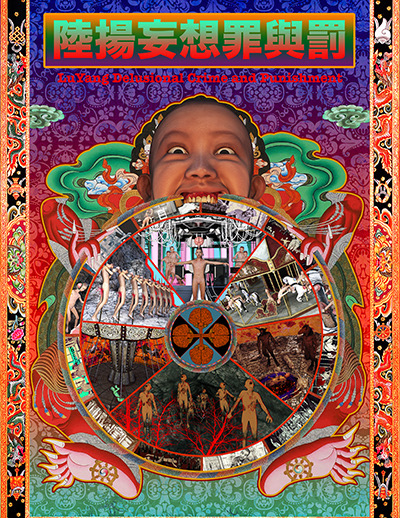

Hearse Delusional Mandala by the artist Lu Yang, shown at the exhibition One World Exposition #like4like. Courtesy of One World Exposition #like4like.

Because the content of the exhibition is widely different from the previous exhibitions at the mall, #like4like has proven that mainstream audiences crave something niche and aesthetically challenging. Apart from the frequent shoppers at K11, the show also attracted massive young audiences who do not typically attend art exhibitions. While the millennial generation has been called “socially conscious, value-driven, and forward-looking,” presenting works that echo the personal values of these youth can potentially turn them into visitors.

But interface is also important. In Hong Kong, where shopping malls proliferate, using them to bring art to the public makes a lot of sense. During the Art Basel month this year, almost every shopping mall in Hong Kong showed art—from masters such as Picasso to the contemporary digital artist Julius Popp. That means that for a Hong Kong audience, seeing art in their everyday lives is nothing new. Curators have to create an interface that transforms the audience’s everyday shopping experience.

When creating the #like4like exhibition, therefore, I integrated technology that encouraged viewers to communicate. While some galleries ban the use of cameras, #like4like used digital culture to promote audience engagement. We provided audiences with the use of Snapchat Spectacles to record and upload their exhibition experience in the “Memories” section of a Snapchat account. #like4like also included “selfie points” with signs, graphics, and mirrors designed to encourage the audience to photograph themselves.

One audience member took a picture of herself licking the mirror as if she was kissing herself; another audience member lay on the floor, initiating Buddha postures in response to a work about reincarnation. Through these immersive and Instagram-friendly exhibition designs, #like4like strived to break away from the uptightness visitors might feel in museums and galleries.

The exhibition also worked to transform the stereotype of selfies—as expressions of digital narcissism and an unrealistic desire for validation through social media. #like4like saw social media as part of the creative potential of self-expression. I wanted the exhibition to provide an interface where viewers could meet themselves.

As they did, they also provided publicity. The rise of social media and digital culture has desensitized younger generations to conventional promotion and marketing. Social power has become decentralized. Digital natives can make formerly fringe groups into powerhouses. Among this “crowdculture”—the term that Cultural Strategy Group founder Douglas Holt coined for the phenomenon—decisions are often driven by word of mouth, particularly if the sources of knowledge and advice are Key Opinion Leaders (KOLs, as they’re called), from politicians to celebrities to social media trend-setters with strong followings. (The Kardashians are KOLs.)

In the commercial world, brands collaborate with KOLs to extend their reach—but the art world has been slower to explore their impact. #like4like became popular among the younger generations in part through the power of the KOLs—which helped us reach a larger, younger audience. For example, one KOL from Hong Kong, called Poortravel, posted a picture of #like4like on Instagram, and within 24 hours, the post received over 9,000 “likes” and 300 comments. As commenters tagged their friends, the very nature of internet communication fostered promotion and engagement.

An Instagram photo taken by a visitor to the art exhibition One World Exposition #like4like. Courtesy of @gnitmiy/Instagram.

Instagram engagement, though, is about more than increasing audience. It’s also about allowing the audience to construct knowledge. Scholar of museum education George E. Hein describes the didactic learning model by which knowledge and information are often transmitted in museums as trying to “instill a specific message in the visiting public.” But this tactic is not the only possibility. #like4like adopts an inquiry-based approach. I crafted an exhibition design that focuses on visitors’ interactions with exhibits. This allows for informal learning among gallery-goers while promoting multiple interpretations of each work by tapping individual viewers’ knowledge and experience.

For example, hundreds of audience members took selfies in front of Chen Wei’s piece “Unprecedented Freedom”—which consists of a neon sign with the title words. “Freedom” immediately caught the attention of audiences, especially in relation to the British colonial legacy in Hong Kong. On Instagram, posts of and selfies with this piece were often captioned with ruminations about what freedom is or comments that directly relate the piece to Hong Kong politics. Other captions were more personal. One spent more than 100 words describing the viewer’s love story. The variety of these posts emphasized that there is no single correct interpretation for this or any work of art.

Now that digital media gives almost every member of a museum audience a platform, museums can welcome visitors as active interpreters. Social media allows “exhibitions” to extend beyond a physical space—to become an open, never-ending event completed by the audience. While opening up engagement opportunities, this phenomenon also reminds audiences that knowledge is always mediated.

The use of social media in #like4like was one of the exhibition’s significant accomplishments. Because of it, I felt like I took more from the audiences than what I offered through my curation. The show taught me that curators can and must use technologies to create more powerful connections among people. Technology can widen the scope of art exhibitions and the power of community engagement.

Send A Letter To the Editors