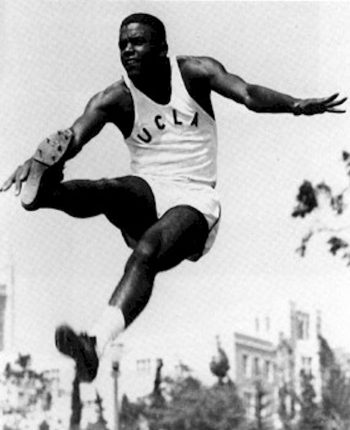

Tom Bradley running track at UCLA, circa 1939. Photo courtesy of the Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA.

The arrival of five athletes, all African American, on the UCLA campus in the late 1930s would prove to be a moment of destiny, not just for college sports but for the United States itself.

The arrival of five athletes, all African American, on the UCLA campus in the late 1930s would prove to be a moment of destiny, not just for college sports but for the United States itself.

These five men could have been called the original Fabulous Five. And that designation was no exaggeration, because they went on to change the cultures of professional athletics, entertainment, the civil rights movement, and politics.

The athletes who played together in the 1939 school year were:

• Jackie Robinson, who would break the color barrier in Major League Baseball in 1947 and become a prominent advocate of racial equality after his baseball years.

• Kenny Washington, who took down the color barrier of the National Football League when he played for the Los Angeles Rams in 1946.

• Woody Strode, who would join Washington with the Rams and later become an accomplished actor in movies such as Spartacus, Sergeant Rutledge, and The Professionals.

• Ray Bartlett, who would go on to serve on the Pasadena police department (at that time, only the second African American) and as a prominent Los Angeles area civic leader.

• And then there was the fifth, Tom Bradley, who would transform Los Angeles into a global city during his 20 years as mayor. He also would make history as L.A.’s first black mayor, and the first in a major city that had a white majority.

At UCLA, these athletes came to know each other, creating a bond of fellowship that lasted for their entire lives.

The decision to recruit a roster of African-American football players came after UCLA had experienced a 20-year drought on the gridiron. At the time, this recruiting decision represented a bid for competitive advantage, since most schools, including rival USC, were uninterested in recruiting black players in that era. Washington and Strode came first to UCLA in 1936, and were followed by Robinson, Bradley, and Bartlett, who would team up in 1939.

Their recruitment helped create an accepting atmosphere at UCLA for African Americans. That was a challenge. African Americans numbered only 50 of the university’s 9,600 students that year. At the time, the campus was predominantly a commuter school. All five athletes lived at home, as no blacks were allowed to reside in Westwood, the neighborhood surrounding the campus where some students lived. For social activities, they would attend a club for African Americans called the Sphinx.

Nonetheless, the school was an oasis in a more hostile environment. “UCLA was the first school to really give the Negro athlete a break,” Bartlett said. Strode later said: “Whatever racial pressure was coming down in the City of Los Angeles, the pressure was not on me in Westwood. We had the whole melting pot, and it was an education for all of us. […] I was just like any other athlete. And I worked hard because there was always the overriding feeling [that] UCLA really wanted me.”

Bradley was convinced that UCLA played a vital role in setting a standard of acceptance for black athletes, and ultimately for African Americans as students and leaders. “Some of the schools with which UCLA had an affiliation did not permit blacks to compete on the same teams,” he said. “And UCLA administration made the decision that no school that would discriminate against its athletes could any longer compete in athletics with us.”

But Jackie Robinson wasn’t so sure that all was as cozy as Bartlett, Strode, and Bradley saw it. He remarked during his UCLA years that he was treated like a hero when playing in front of a huge crowd on the football field but as soon as the game was over he was simply Jackie Robinson, the Negro.

Jackie Robinson during his track-star days at UCLA. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

What is clear is that that recruitment of the athletes was news off campus as well. Nationally, by the late 1930s, no more than 38 African Americans suited up for major college football across the country—none in the South. “Three African-American players out of eleven in the starting lineup was highly unusual for the time,” says Kent Stephens, curator and historian for the College Football Hall of Fame in South Bend, Indiana.

UCLA’s roster of black players on the football team made it the most racially integrated squad in college football history. “We have yet to find another single coach in the history of football that has had the guts to play three of our race at one time and have [four] on the squad,” a reporter for the Chicago Defender, a newspaper for black readers, wrote later in the year.

In contrast to the four football players, Tom Bradley, who had been an all-city football player at John H. Francis Polytechnic High School, received an academic scholarship. He eventually decided against playing for the football team, preferring to focus on competing in the 440-yard run, the 880 races, and the 1,600 relay in track. That race fit perfectly his tendency to be something of a loner. He later said: “The whole business of competition—in track, particularly, because you’re kind of one-on-one in track—involves a kind of discipline you have to develop for yourself …. I think it really became part of my lifestyle.”

But Bradley did have teammates on the track-and-field team, including the four star football players, who competed in track during the spring. There were three other black runners on the team—Tom Berkley, Bill Lacefield, and James LuValle, who ran at the so-called Nazi Olympics in 1936 and became a scientist and an administrator at Stanford. These athletes formed lifelong fellowships that included several reunions.

The best athlete of the group, Jackie Robinson, lettered in four sports at UCLA, the only Bruin to accomplish the feat. Robinson won the NCAA championship in the long jump (then called the broad jump) while also leading the Pacific Coast Conference in scoring one year for the basketball team. His worst sport was his future professional avocation: baseball, in which he batted .097 and committed 10 errors in his single season.

Many of the other athletes excelled in multiple sports. Bartlett also played four sports but didn’t earn a letter in all like Robinson. Washington threw the shot put, and Strode the discus and shot put. Washington played baseball as well. Rod Dedeaux, who coached USC baseball for 45 years and scouted for the Dodgers, said he thought Washington had a better arm, more power, and more agility than Robinson. (Washington got a tryout with baseball’s New York Giants in 1950, but by then he was past his prime.)

Each of the athletes had his own life, shaped by the fact that they lived at home and held down part-time jobs along with other personal responsibilities. Robinson tended to avoid social activities on the UCLA campus. Bradley and Strode joined different black fraternities, while Bartlett and Washington concentrated on academics, as did Bradley. None of the athletes graduated in four years. What held them together was their dedication to sports.

Of the five, Robinson was the one who most vigorously battled racial discrimination throughout his entire life. The other four, while acutely aware of the racial climate in their lives, adopted a more passive approach of “going along to get along,” which was the safest mode of operation in those days.

Robinson devoted a great deal of his life after he broke the color barrier in baseball to working for civil rights. Strode had little to do with the civil rights movement. He believed that what he accomplished on the field and life was the best way to break down prejudice. Bradley fought discrimination in the Los Angeles Police Department and as mayor, while Washington and Bartlett worked within the political system to seek racial equality.

Some relationships among the five were closer than others. Robinson and Bartlett, who grew up together in Pasadena, were lifelong friends. (Bartlett represented Robinson, who died in 1972, as grand marshal of the 1999 Rose Parade.) Strode and Washington were like brothers; Washington was emphatic that the Rams sign Strode if they wanted him to play. And Bradley and Bartlett were in frequent touch as they became policemen and civic leaders in Los Angeles.

Their legacies remain strong today.

Send A Letter To the Editors