Photo courtesy of Aaron Salcido.

Journalists seemed to be heroic figures when they covered civil rights, poverty, pollution, the Vietnam War, and Watergate. But more recently that story has become confused.

Journalists are sometimes victims of layoffs as newspapers close their doors. Or they’re targets, as President Trump accuses the media of publishing “Fake News,” and threats fill reporters’ social media feeds and email inboxes. And often, journalists are tuned out, as readers and watchers grow frustrated and give up on media outlets that don’t reflect their concerns, from climate change to education.

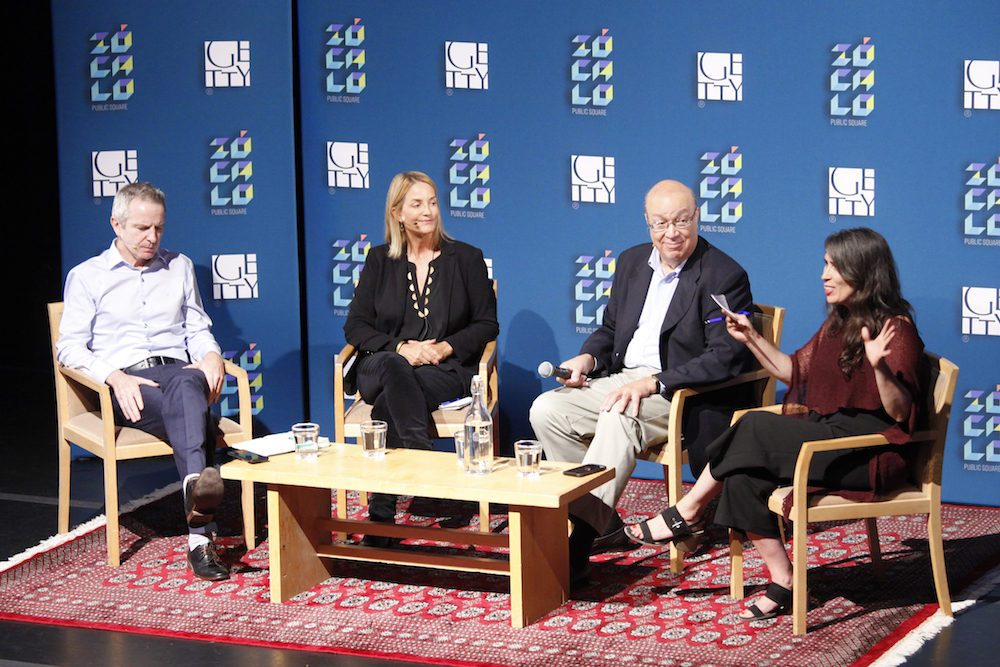

What do journalists owe society? The world itself has changed faster than our idea of the news has, with diverse readers looking for reflections of themselves that news organizations struggle to provide, said a panel of veteran journalists and editors at a Zócalo/Getty event titled “Is Journalism About Social Justice?”

Before a lively crowd at the Getty Center in Los Angeles, moderator Michelle Holmes, head of partnerships at the Alabama Media Group, began by asking what social justice journalism means “in a nation of deeply divergent and sometimes shifting values.”

Furthermore, she asked, how is a journalist committed to social justice “that different than just a journalist deciding how the world ought to be?”

John Mulholland, editor of Guardian US, said that the need to distinguish journalism that addresses social justice as something special is itself a very American impulse. In the U.K., journalists routinely campaign on certain topics; such journalism is “part of the DNA” of British journalism and is done by papers on both the left and the right.

“Over here … there has been a presumption of objectivity, which has been a tenet of American journalism. It’s less the case in Britain where there is a history of campaigning journalism,” Mulholland said.

He added that he’d never thought of social justice journalism as unique from the other parts of a paper’s coverage, including lifestyle and culture or sports, but it becomes an obligation of the position. “You’re gifted with some degree of power—less probably than was 20 or 30 years ago,” he said, “but there’s still some power in having that voice and that platform and I think you have to give it to communities and other people who don’t have it.”

But the question of who controls the platform and who reads the paper has become more complicated than it was even a decade ago. On social media, readers now want to have a say in what the news covers. And while this seems like a new trend, it has been a part of American journalism in the past.

Veteran journalist Adam Clayton Powell III, director of Washington programs for the USC Annenberg School of Journalism, explained that until 30 years ago broadcasters were required to do “ascertainment,” where journalists had to go out into the communities they served to ask what they thought was interesting. That still makes sense, since readers often know more than journalists about their communities, Powell said.

“We aren’t by any means the center of all wisdom—we have to keep listening, and watching what others are trying to tell us,” he said.

Simply raising the question of social justice adds extra ethical layers to covering the news. Los Angeles Times photojournalist Carolyn Cole observed that when she goes into a disaster zone or crisis, “I am the eyes for people who are not there.”

But the power of witnessing has limits. Cole recalled going to Iraq before the second Iraq war in 2003 to try to introduce Americans to individual Iraqi families. “One of the great failures of American journalism was that we failed to stop that war,” she said. And when she returned to visit a family that she had profiled after years of occupation, they were very angry. Another subject, a woman in Afghanistan, had suffered negative consequences after her photographs were published.

During the event, the panelists kept returning to the struggle to have more diverse reporters and editors in newsrooms. When Holmes asked Powell why lack of diversity in newsrooms has remained a persistent problem for decades, Powell recalled that when he arrived as an executive at NPR, “they had no minority correspondents, anchors, senior editors, executive producers and it shocked me at first. And then, I realized that I should have been able to tell from the sound that that was the case.” Within a few years, NPR increased numbers and had many success stories.

Mulholland said that after the El Paso shooting, the Guardian realized “our staff wasn’t nearly diverse enough to be able reach out to those [Latino] communities and speak to them in a way that was as empathetic as we would want to.” In response, the paper has been recruiting more diverse journalists while teaming up with activist organizations that work on Latino issues. The paper has also been able to portray new perspectives, he said, by bringing diversity fellows into the newsroom and helping them to pursue personal stories that resonate with readers on social media.

Mulholland noted that NGOs and social justice organizations are now providing people with opportunities for activism—and they look like news sites. “They can present themselves as almost advocacy-style journalists,” he said, adding that such sites include buttons above these features that say “join,” “act,” or “give.” Mulholland suggested that these organizations may be more adept at providing social justice than traditional media.

Powell added that there are other types of diversity, including geographic diversity. He remembered being a news director in New York, where he put pins on a map whenever they covered a story. He noticed one day that they had no pins in Northeast Queens, which had a population of about 350,000 people. He assigned a reporter to go to the neighborhood and see what people were talking about. And though the reporter grumbled, he returned with multiple stories. “A lot of what journalism needs is to identify those areas without any pins and find out what’s going on there.”

The fraught question of whether it’s possible for journalism to do right by everyone came to a head in a question from an audience member, who asked whether the news should cause people to panic on climate to get them to take action or whether that’s causing too much anxiety for children.

“People should be frightened. I’m sorry if the children panic,” replied Cole, adding that young people will need to be leaders on environmental issues.

By the end of the evening, it seemed that climate change is galvanizing new thinking about whether power lies within journalism at all. The final audience question of the night asked whether money is influencing how the media covers environmental issues. Mulholland said that while fossil fuel companies were able to get U.S. media to portray climate change as “a theory, not a fact” from 1985 to 2000, many companies now think differently about climate change because they have to answer to their employees and shareholders.

“I do think there’s a great deal of hope in the pressure being brought on bosses,” by millennial employees, Mulholland said.

Send A Letter To the Editors