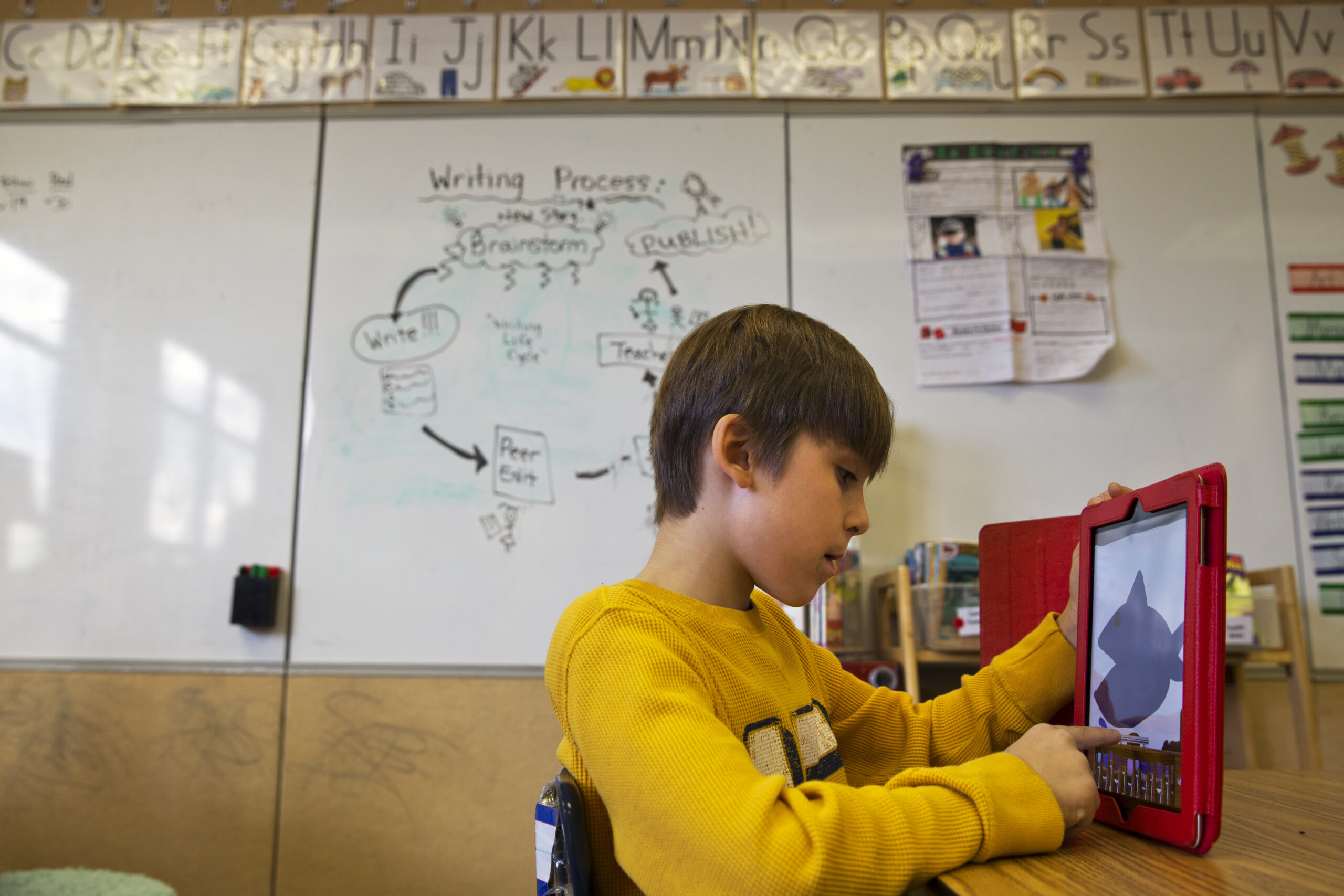

Student online learning in classroom. Courtesy of AP/Jacquelyn Martin.

The start of the new year at the middle school where I teach in South Los Angeles has been stressful; the rapid spread of the Delta variant shook us from the tenuous sense of security we were lulled into over the summer. Fans blow in the hallway, dual air filters hum in the classrooms, staff screen kids for symptoms at the gate, and everyone wears masks.

The stakes are high: the surrounding community was ravaged in earlier waves of COVID-19 as family members in service jobs or working in nearby garment factories brought the virus home to crowded, multi-generational, and multi-family households. But after a year of mostly distance learning amidst the traumas of the pandemic, the kids need to be back in the classroom, and they need us there to support them.

Yet as we return, and as we try to reinvent our school to be as physically and emotionally safe as possible, there’s a lot my colleagues and I learned during our unexpected time as a Zoom school.

Our first few months online were a struggle. My sixth and eighth graders often signed into their Zoom late or for the wrong class periods, had trouble finding the materials for their assignments, and turned off their cameras.

My email would ping with Zoom notifications from students trying to join my English class hours after it had ended. They’d leave comments in the Google Classroom stream: “Mister, where are you?” or “When are you starting class?” They’d turn in blank assignments, I’d return them, and they’d immediately turn them back in again. After requesting cameras be turned on so we could all be present together, I’d view a half dozen or more ceiling fans.

Plus, it was a challenge to build relationships with my students. There weren’t opportunities to chat at the door, to check in while they worked, to guide to the right book from my classroom library. My frustration mounted as my expectations for myself and for them weren’t being met.

By mid-October, after the first quarter had ended and with the staff temperature near boiling, our administration devoted a weekly meeting to checking in and recalibrating. What was working and what wasn’t? What did the kids need from us now? What did we need now?

In Zoom breakout rooms, bleary and slumped low in their chairs or leaning on their knuckles, colleagues vented. They were spending more time planning than they had since they were first-year-teachers, but not seeing results. Kids were not completing assignments and not responding in our interactive lesson platforms. And we were just burned out from staring at screens.

Being asked how I felt—and being given the space to be vulnerable and honest in answering—made me feel as if a weight had been lifted off my shoulders.

We had to let go of our hold on what things had been like before the pandemic and accept the reality of what was: We all were learning, on the fly, a different job. Our students, facing spotty internet and often difficult situations at home, were also being asked to do something they’d never done before.

As a staff, we responded by simplifying and streamlining, both in our classrooms—where we set common expectations for everything from assignment names to office hours and reduced the clutter of notifications—and our mindsets. This meant a recommitment to building relationships—one of the only tools we had to keep students engaged, and to engage with one another. We built in time during our staff trainings and meetings as well as during our classes just to check in with the community, catch up, and see how everyone was doing. Over winter break, I mailed each of my students (over 120 of them) a personalized postcard just saying hello and that I looked forward to seeing them after the holidays.

The new and improved classroom. Photo courtesy of Carl Finer.

Research supports this deliberate recalibration of our professional and student relationships.

The Search Institute, a youth development nonprofit research center, defines a “developmental” relationship as a close connection between a young person and an adult or peer that powerfully and positively shapes the young person’s identity and helps them develop a thriving mindset.

Middle school students who reported strong developmental relationships with teachers were eight times more likely to stick with challenging tasks, enjoy working hard, and know it is OK to make mistakes when learning. They also were more likely to have higher grade point averages, feel connected to school, and feel culturally respected and included.

Last spring, after examining district-level data on relationships and engagement during distance learning, our organization’s diversity, equity, and inclusion committee, which I’m a member of, gathered two focus groups of our most vulnerable students—middle schoolers with disabilities and high schoolers who identify as LGBTQ+—to find out what it took to keep them engaged in online school. The belief was that listening to these students could help us build support systems that, by addressing their needs, would also serve everyone better.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, both groups praised teachers who proactively built trusting relationships through open (often private) communication and found ways to show they cared. Surprisingly, it didn’t take much to make a difference.

Students said:

“People just need to be asked how they are doing.”

“My best teacher talks to me privately. If I’m having trouble with something, they’ll message me in the chat or pull me into a breakout room or stay after class and ask what’s going on or how they can help.”

“One time a teacher noticed I was off, that I was kind of depressed, and asked me if I was OK. I’d been going through a tough time, and it meant so much that they just asked. I was able to do my work after that.”

At the end of last year, I asked my journalism students to share their experience of living during the pandemic in a photo essay, and they responded with images capturing their frustrations with screens and boredom of quarantine as well as challenging family situations. They also took photos of the things that gave them joy and connection: new pets, escaping into nature, time with family. I asked—and in response, they shared their resilience and creativity.

Now, back with these students in-person, I’ve rebuilt my classroom environment to be more warm and welcoming, even as the environment outside the school frays. Plants and framed art line my walls along with bean-bag chairs and a couch from Target. The rows of desks have been moved into groups along with much of the learning. Each class created their own Spotify playlist, a practice I started during distance learning, and we play these during independent work. And, in my assignments, using technological tools like interactive collaboration boards, Google Forms, and our class website along with old-fashioned, desk-side conversations, I make space for students to shout out classmates, share how they are feeling, and reflect on what matters most to them.

The personal and mental health challenges we all still face as the pandemic continues are immense. But fortunately, one of the most impactful tools we have to cope with those challenges is simple.

Just ask.

Send A Letter To the Editors