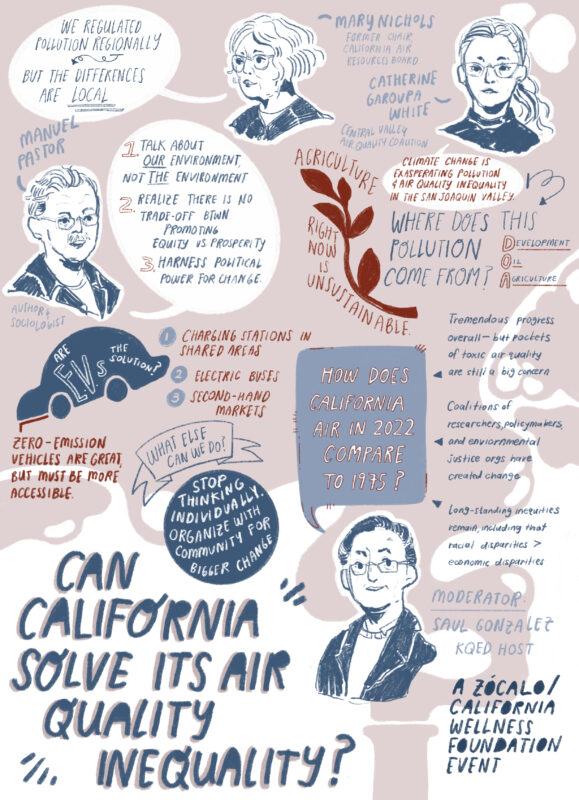

From left to right: Saul Gonzalez, Manuel Pastor, Mary Nichols, and Catherine Garoupa White.

The Los Angeles City Council voted unanimously this week to phase out fossil fuel sites and ban new oil and gas wells.

That kind of victory was once inconceivable for California’s environmental justice organizations, said USC sociologist Manuel Pastor, a panelist at last night’s Zócalo/California Wellness Foundation event, “Can California Solve Its Air Quality Inequality?” But the win, a decade in the making for the grassroots coalition STAND-L.A., shows how far these organizations have come. Today, they work directly with researchers and policymakers to achieve their goals. This was one of the major takeaways of the evening: making progress in combating air pollution, which is distributed unequally across racial and economic lines around the state, requires individuals and organizations to join forces.

Moderator Saul Gonzalez, KQED correspondent and co-host of The California Report, began the discussion by looking back to 1985. “When I take a breath of California air in 2022, how does it compare,” he asked—generally speaking—to air quality back then?

Former California Air Resources Board chair Mary Nichols recalled that when she moved to California in 1971, the state violated federal clean air standards almost 250 days of the year. “It has improved,” she said. However, she cautioned, “the picture is not a steady line in the direction of progress by any means.”

Pastor, whose new book, Solidarity Economics, co-authored with fellow USC professor and public policy expert Chris Benner, explores how people can lead progressive social change, agreed. He also pointed to overall progress as obscuring research showing that your race and ethnicity remains the greatest single factor in determining how unhealthy your air is, regardless of your income or location. Unequal distribution of polluted air due to factors like freeway location and zoning remains “a reflection of structural racism.”

Climate change, which causes record temperatures and wildfire smoke, only exacerbates this inequality, said Central Valley Air Quality Coalition executive director Catherine Garoupa White. In the San Joaquin Valley, which ranks among the nation’s worst regions for air pollution, “we suffer epidemic levels of sickness,” they said, and “it’s not distributed equally. There are particular neighborhoods where people of color, low-income communities, and all of these other social and economic vulnerabilities are layered.”

Gonzalez asked Garoupa White to imagine the year 2050: What do you fear if temperature rise continues at the rate of current projections?

“We need to have hope that things can be different,” said Garoupa White. “There are a lot of solutions. There are a lot of things that we can transform and change now so that in 2050, that won’t be our reality,” including designing “resilient communities where people will be protected regardless of what happens.”

By Soobin Kim.

Still, it’s an open secret that agriculture in the San Joaquin Valley today is not sustainable. “That’s why we have the worst air pollution in the United States, because we are over-exploiting the system. We are putting more pollution into it than it can possibly sustain,” Garoupa White continued. California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), will help alleviate some of this burden. But, they said, “it would be a lot better if we crafted, regionally, a vision for what type of agriculture we wanted.”

Looking back, Gonzalez asked the panelists, what did we get wrong when it comes to policy around air pollution?

Considering air quality from a regional approach rather than at a city, community, or neighborhood level, said Nichols in reference to the federal Clean Air Act. “What that didn’t take into account is that at the local level, and where people actually are breathing this stuff, there really are differences,” she said. “And it didn’t take into account that not all pollutants are equally distributed, so some types of pollutants, like for example, the toxic chemicals that come out of diesel vehicles, are going to be more harmful. There are more of them, and more people will breathe them when they’re right next to the freeway or the port or the distribution center.”

What’s one solution—possibly even painful—that you would embrace today, asked Gonzalez, for cleaner air?

“The oil industry—let’s remove their subsidies,” said Garoupa White. Emission credits and market-based approaches are not working, they continued. Rather, they are “concentrating pollution in low-income communities and communities of color” while allowing oil companies “to take credit for something that happened in some other place.”

What about land use policy, Gonzalez asked: How much will this impact the environment?

Land use policy plays a major role, said Nichols, and can even be a form of discrimination. “If you continue to require people to move further and further away from where they work, or from where there’s opportunity, you’re also making it impossible for them to use mass transit in many cases or to live a healthy life by walking to various kinds of amenities,” she said.

Before wrapping up the discussion, Gonzalez asked a recurring question raised in the live YouTube audience chat: What is something that everyday people can do to help their neighbors breathe easier?

Make this more than an individual fight, said Pastor.

“My own behavior isn’t going to change things unless I link up with other people who want to change the concentration of power and change the policies that we pursue,” he said. Pastor called on listeners to “figure out how you can organize your community to accept more affordable housing, to change the zoning, to push for free public transportation, to get the state of California to pay special attention to hotspots, to make sure that we’re dealing with the inequities in the Central Valley.”

Send A Letter To the Editors