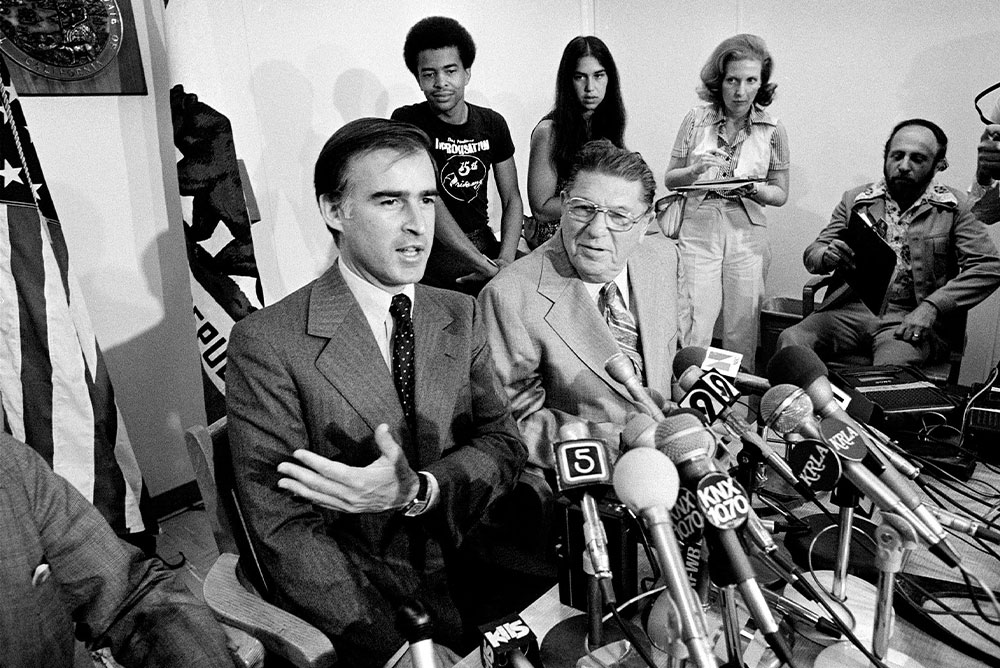

California Gov. Jerry Brown (left) and tax reformer and executive director of the California Apartment Owners’ Association Howard Jarvis (right) at a news conference in Los Angeles regarding Proposition 13 in 1978. Courtesy of AP Images.

Lawmaking by voters through the ballot initiative process has been popular in California for more than a century.

So why is there near constant talk of altering or limiting California’s direct democracy, including now, in the aftermath of last year’s gubernatorial recall election?

There are two answers to that question, one visible, and one hidden. On the surface, would-be reformers usually say that they want to make citizen lawmaking more effective and easier for everyday Californians to understand. But below the surface, attempts to reform the process reflect profound tension, and disagreements about who—voters or elected officials—should exercise dominant political power.

I know this pattern firsthand because of my peculiar experience. As the former president of the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association, I’m forever linked with the most famous initiative in California history, the property tax-cutting Proposition 13. Over the past 30 years, I’ve been associated with four separate committees that pursued reform of the ballot initiative, the tool that allows voters to decide whether to make laws or constitutional amendments.

As Californians consider current efforts to change the initiative and recall, thinking back on these four efforts is instructive.

Action of the legislature created three of the committees. A fourth was made up of political activists, special interests, and citizens groups. This fourth committee was the one that achieved changes to the system, notably securing legislative approval of some of the modifications proposed by previous commissions.

And that is no irony. I’ve learned that if you’re going to change direct democracy, it’s best to work from outside the government—just as you do in using direct democratic tools.

The history of the initiative and its direct democracy cousins, the referendum and recall, extends back more than a century to the Progressive Era. As former California Gov. Hiram Johnson, who led the establishment direct democracy in California in 1911, said in his first inaugural address, the initiative, referendum, and recall, are not panaceas for all our political ills, “yet they do give to the electorate the power of action when desired, and they do place in the hands of the people the means by which they may protect themselves.”

If anything, Johnson undersold direct democracy’s influence. At the beginning of the 21st century, then-Assembly Speaker Bob Hertzberg, who has long been involved in initiative reform efforts, wrote: “The initiative process in California has evolved into a virtual fourth branch of government.”

While there is always room for tinkering to make something better, it’s important to be careful not just about the details of proposed changes, but the motives people have for tampering with public institutions. Change efforts often are thwarted by concerns over shifts in politics and power.

That’s been part of the story of all four reform commissions I served on. The first, the 15-member Citizen’s Commission on Ballot Initiatives was created by a legislative resolution. The governor, senate, and assembly each appointed four members, and the Attorney General, Secretary of State, and the County Clerks’ Association were also represented. I was appointed by then-Gov. Pete Wilson.

In early 1994, the commission issued its recommendations, including seeking legislative review of initiatives before they went to the ballot, and allowing corrections and changes by the measure’s proponents even after it qualified for the ballot. The group also recommended extending the period for gathering signatures to qualify measures from 150 to 180 days (to make qualification a little cheaper and easier)—time is money—and expanding financial contribution disclosure requirements on initiative campaigns.

Two years later, in 1996, Gov. Wilson again appointed me to the 23-member California Constitution Revision Commission, which was made up of other elected officials’ appointees This attempt at reckoning with California’s long constitution delved into direct democracy.

One constitutional revision commission proposal was to allow statutory initiatives to be amended by legislators after six years. I opposed this, and other recommendations, because they gave the legislature more power, and the people, through the initiative process less. And in practice, it wouldn’t work; initiative sponsors could block legislative amendments of initiative laws by making their initiatives into constitutional amendments, which cannot be amended directly by the legislature. “The end result,” I wrote in opposition to the idea, “will mean more amendments to the constitution, burdening a document the [commission] hoped to condense.”

In 2001, Hertzberg, who was leading the assembly at the time, convened a 34-member Speaker’s Commission on the California Initiative Process. Like the first commission I served on, it sought to make it easier to gather petition signatures and to disclose more public and financial information about measures.

But the lead recommendation of the Speaker’s Commission was a call for the return of an indirect initiative—a type of initiative, abandoned in the 1960s, which allowed voters to make a proposal to the legislature. This effectively gave power to the legislature to change an initiative even after it qualified. It did not gain traction, precisely because of the transfer of power to politicians.

Interestingly, all three of these government-sponsored commissions released their results during election years. Legislators, not interested in angering a public fond of the initiative process, did not move forward with any of the recommended reforms.

Another decade would pass before I got pulled into another initiative reform. In 2014, Common Cause, the League of Women Voters, and the California Chamber of Commerce joined to create a committee not sponsored by government resolution.

While the approach was new, this effort advanced ideas that had been part of previous reform attempts. These included extending the time to qualify an initiative from 150 to 180 days, providing more public information on ballot measures and how they were financed, and greater flexibility and space for negotiations—specifically, allowing an initiative’s proponents to pull a qualified initiative if the legislature comes up with an acceptable alternative to the proponents’ proposal.

These ideas all had something in common: they enhanced the power of the people, not the legislature. That’s why, in my view, all three recommendations eventually became law.

Of course, attempts to enhance the legislature’s power, at the expense of voters, continue—and once in a while they break through. Back in 1996, the Constitutional Revision Commission had suggested limiting citizen initiatives that changed the constitution to the November general election ballot—while allowing the legislature to put its own proposed constitutional amendments on any ballot they wanted (general election, primary and special election ballots).

This provision favoring the legislature wasn’t enacted then, but it returned in the 2010s—not through a commission, but through legislation that Gov. Jerry Brown signed.

Supporters of the change claimed that this was a democratic reform—that it would be better to have initiatives voted on when a larger voter turnout occurs during November elections. But the motives were more political; studies showed that turnout by liberals and progressives was stronger in November, and the Democrats who changed the law wanted initiatives to face a more friendly audience.

Today, there are new ideas being discussed, both in the legislature, and by outside groups. Current proposals include reforming the recall in light of the unsuccessful effort to remove Gov. Gavin Newsom; curbing the power of special interests to control what voters see on the ballot, and adding more deliberation to initiative campaigns.

Even when considering novel proposals, the best way to understand California arguments over direct democracy is as political contests between the power of the legislature and other elected officials, and the power that the people have in the legislative process.

The initiative power can challenge the status quo and advance different political ideas than the dogma favored by those in power. In the current California political environment, it is no secret that the dominant political power belongs to the Democratic Party and a more progressive ideology. Challenges to that thinking can come from initiatives that gain wide support from the voters. You can see such challenges in recent initiative and referendum results—keeping the death penalty and cash bail, and allowing workers to continue freelance and independent work—that did not follow the majority thinking in the Democratic legislature.

Those tempted to limit the people’s power and enhance their own should be careful. Polling last month from the Public Policy Institute of California reaffirmed what past polls discovered. Likely voters consider the initiative process a good thing as opposed to a bad thing by a more than a two-to-one margin, 67 percent to 31 percent.

Of course, that doesn’t mean the people are opposed to reform. The PPIC poll found that likely voters would consider major changes (33 percent) or minor changes (48 percent) to the initiative process.

I’m among those who would like to see reform. Extending the qualification time from 180 days to a full calendar year is worth considering as a way to help more grassroots groups and individuals to use the initiative power, I’d also like to see the ability to write ballot titles and summaries moved from the partisan attorney general to a more neutral body. This issue was discussed endlessly in the 2014 reform group but ultimately did not advance.

The most important thing is for reform proposals to be scrutinized carefully, especially by voters, to guard the people’s initiative. In an election year, I don’t think we’ll see any big changes to the process, but there’s always 2023. And should we see another commission appointed or another committee convened—particularly by anyone other than the legislature—my schedule is open.

Send A Letter To the Editors